New Hampshire holds the first presidential primary of the season on Tuesday, February 9. Voters who are registered as independent get to participate in either party’s contest, one of the factors that makes the primary much more unpredictable than a general election. After Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush won here, analysts commonly cited the “rule” that no one could get to the White House without winning the New Hampshire primary. But then Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Barack Obama all lost New Hampshire and became president anyway.

At least New Hampshire can still claim that no one since 1968 has gotten a major-party nomination without finishing at least second in its primary—something of a self-fulfilling prophecy, given that so many candidates who finish third or worse soon run out of money and drop out. John Huntsman ended his candidacy immediately after finishing third in New Hampshire’s 2012 primary; it is assumed the Republican field will thin out after this year’s election. The maps below detail the different voting histories of New Hampshire’s 10 counties and what they mean for the candidates in 2016. (Also see: “The 11 Maps That Explain the Iowa Caucuses.”)

THE DEMOGRAPHICS

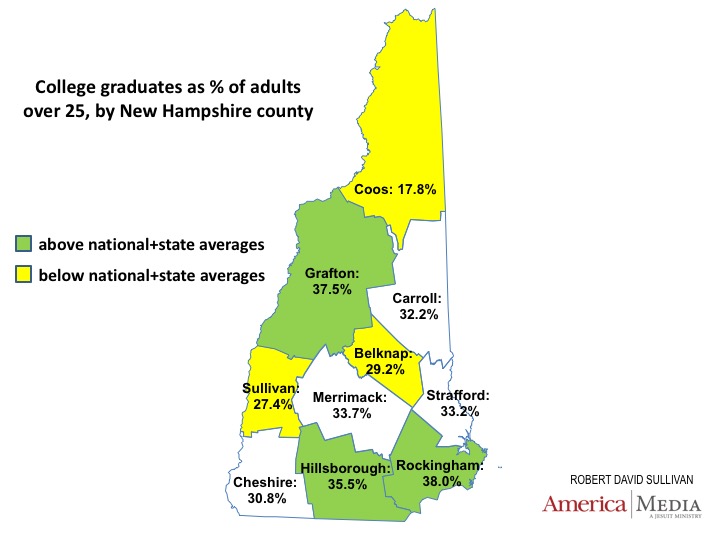

New Hampshire is the first primary or caucus state with an above-average share of college graduates (34.4 percent of adults over 25 have at least a four-year degree, compared with 29.3 percent nationally and 26.4 percent in Iowa). Since front-runners Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump have generally had better poll numbers among those without a degree, their rivals see New Hampshire as an opporunity for an attention-getting win. But not all of New Hampshire fits this image. The state’s college graduates are disproportionately found in the southeast, part of Boston’s sprawling metro area, and in the “Vermont east” county of Grafton (home of Dartmouth College). The Boston exurbs are where most of the votes are in New Hampshire, but there are other areas where a self-styled populist like Donald Trump could do well. Three counties lag behind the national average in college attainment: Sullivan (including Claremont, a former mill city that has lost its manufacturing base), Belknap (an older-skewing area of retirement and resort towns), and Coos, a blue-collar area at the top of the state that hit its peak population back in 1940. In Berlin, the largest community in Coos County, only 10.8 percent of adults over 25 have college degrees, or about one-third the national average. Coos doesn’t contribute a lot of votes, but it can make a big difference in a close primary, and it does not have the same voting habits as the bedroom communities along the Massachusetts border.

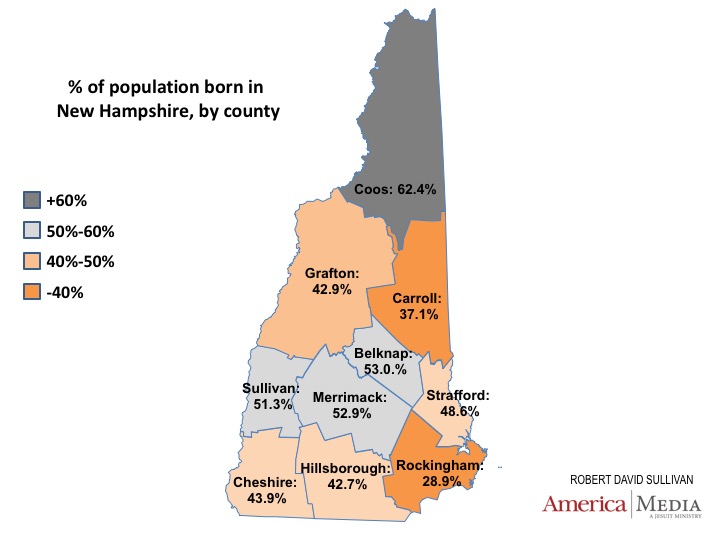

Only 42 percent of New Hampshire residents were born in the state, according to a 2014 New York Times analysis of Census data, and 25 percent of all residents came from Massachusetts; no other state has been “invaded” so extensively by another state. If you’re looking for authentic New Hampshirites, head north and west, especially to forlorn Coos County. But more than half of the state’s voters are in Hillsborough and Rockingham counties, both along the Massachusetts border, where outsiders are the majority.

THE DEMOCRATS

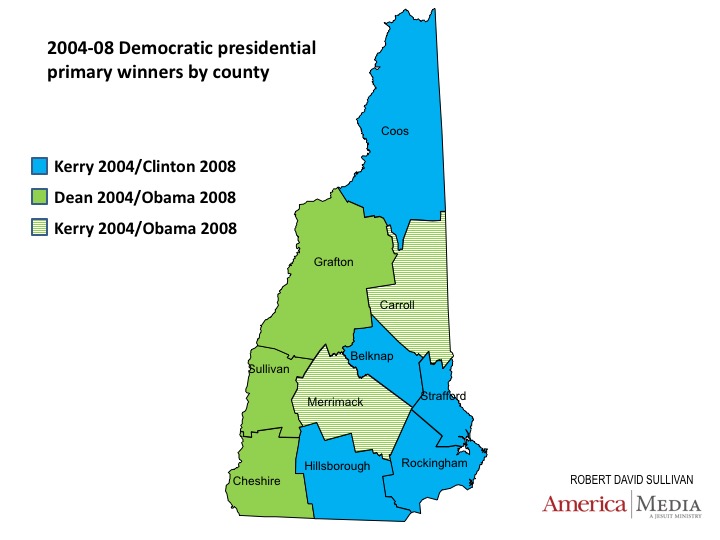

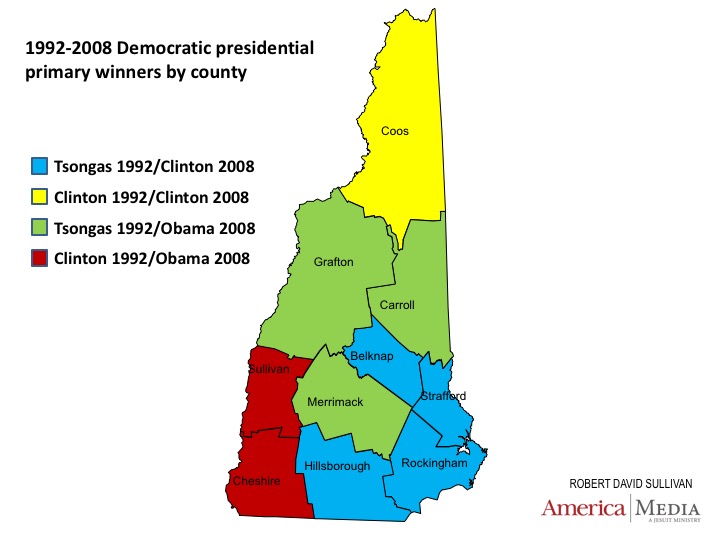

Democratic primaries in New Hampshire have long been dominated by the state’s two most populous counties, Hillsborough and Rockingham, which happen to be the same counties with the largest influx of former Massachusetts residents. Hillsborough, along with smaller Belknap County up north, has voted with the winner of every Democratic presidential primary going back to at least 1968. This usually means an edge for candidates from Massachusetts (John Kerry in 2004, Paul Tsongas in 1992, Michael Dukakis in 1988), but Hillsborough did join the rest of the state in supporting Jimmy Carter over Ted Kennedy in 1980, either because he was too liberal or because there weren’t enough ex-Bay Staters living here yet. (Rockingham, which includes Portsmouth and is the more touristy of the southeast counties, did back Kennedy.) The three Connecticut River counties of Cheshire, Grafton and Sullivan seem to look west rather than south, and they supported former Vermont governor Howard Dean over Kerry in 2004. They were not enough to get Dean closer than 12 points behind Kerry statewide. In 2008, Barack Obama added Carroll and Merrimack (Concord) to the Dean column and lost statewide by only 3 points; Bernie Sanders will need all of these counties to beat Hillary Clinton this year. As for Clinton: does going to Wellesley College in the 1960s make her an honorary Massachusetts resident who can rightfully claim Hillsborough County as she did last time?

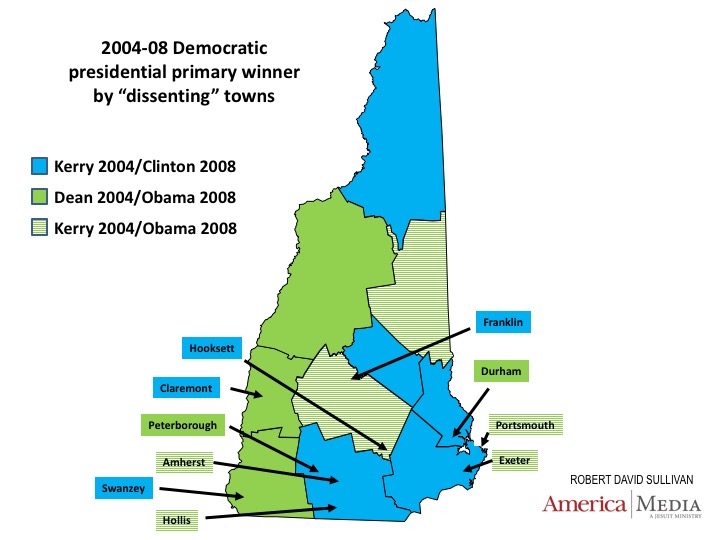

Compared with Iowa’’s neat little squares, the counties in New Hampshire are fairly large and complex, so it’s worth drilling down (sorry, Sarah Palin) to the town level. The biggest county, Hillsborough, gave Hillary Clinton most of her statewide victory margin in 2008 (she won it by 5,654 votes and won New Hampshire overall by 7,589), but it’s not all Clinton territory. She won by double digits in Manchester and Nashua, the biggest cities in the county and in the state, as well as in the Massachusetts border towns of Hudson and Pelham. But Barack Obama won easily in Amherst and Hollis, smaller towns that seem to be just to the west of Boston’s sphere of influence, and Peterborough is a classic northern New England liberal town that backed Howard Dean in 2004. Bernie Sanders will have to win these “dissenting” towns by solid margins in 2016, as well as Obama toeholds in the southeastern parts of the state, including Durham (home of the University of New Hampshire), and the seacoast communities of Exeter and Portsmouth, settled before the state’s population boom from the 1960s through the 1980s.

Clinton, for her part, has opportunities in the smaller cities with industrial histories, like Claremont and Franklin, that dot the more Vermont-y parts of the state.

Hillary wasn’t the first Clinton to run in the New Hampshire presidential primary, but her base of support in 2008 was quite different from that for husband Bill in 1992. Hillary Clinton’s base in newly suburban Hillsborough and Rockingham counties mirrored the support for Paul Tsongas when he beat Bill Clinton in 1992. Bill Clinton did better in more classically New England communties in the southwest—for example, getting a plurality in the city of Keene, formerly known for its pumpkin festival. The only county won by both Clintons has been Coos, the blue-collar area at the top of the state. There aren’t many votes in Coos, but its longstanding aversion to the more culturally liberal Democrat on the ballot could cost Bernie Sanders a close election.

THE REPUBLICANS

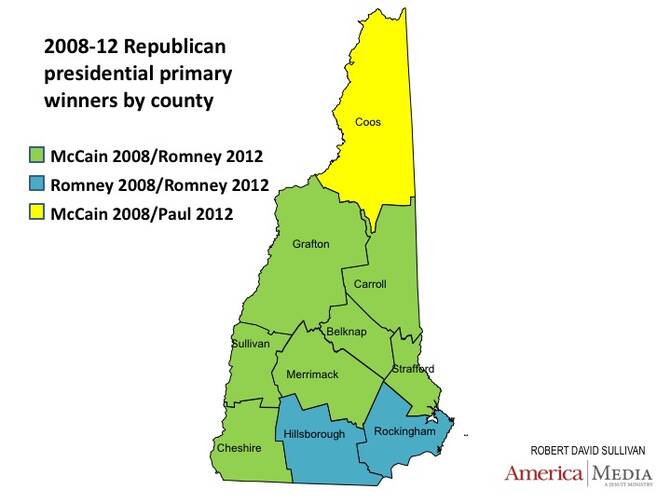

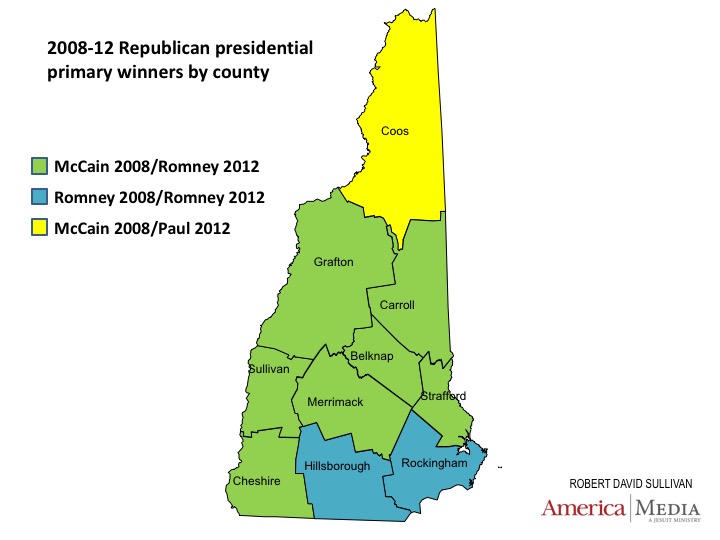

In contrast to the Democratic side, the two most populous counties in New Hampshire have not determined the winner of all recent Republican contests, as former Massachusetts governor Mitt Romney learned in 2008. Emphasizing his fiscal conservatism, Romney won most of the bedroom towns along the Massachusetts border, but his northern reach was not as far as Hillary Clinton’s. In his paradoxical role as a “maverick” with decades of Washington experience, John McCain not only swept the small towns in the north and west of the state, he took the older southeastern cities including Manchester, Dover and Rochester. In the primary four years later, Romney assumed the role of establishment candidate and won nine of 10 counties against libertarian Ron Paul. Contrarian Coos County was the holdout, but Paul also came within 10 points of carrying Grafton, Sullivan and Cheshire counties in the west—winning most of the small towns but falling far short in cities like Keene and Lebanon.

So we have the button-down, technocratic Romney suburbs in the south; the relatively bipartisan, maverick McCain cities throughout the state; and the libertarian Paul towns in the north and west. Does the 2016 field fit this paradigm? Or is Donald Trump the candidate who can appeal to all of them?

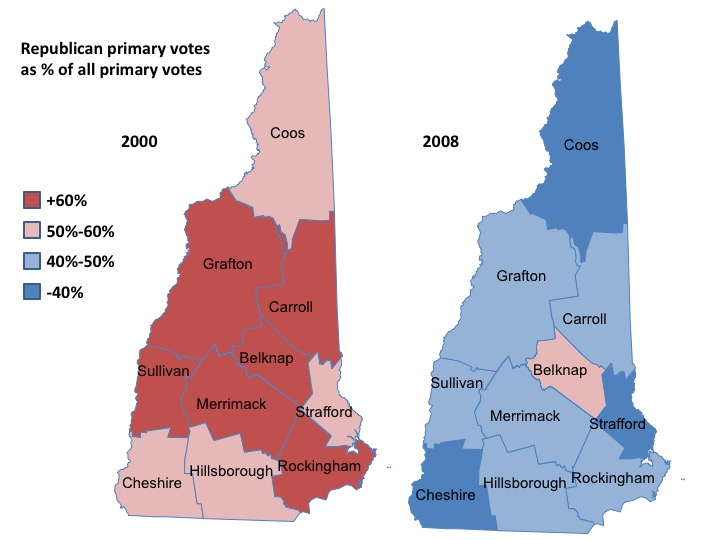

One potential problem for more moderate candidates in the New Hampshire GOP primary is that the state’s center of gravity has shifted toward the Democrats in recent years. In 2000, when John McCain beat the more orthodox conservative George W. Bush by 19 points, more people voted in the Republican contest in every county, even though Democrat Al Gore was facing a serious challenge here from Bill Bradley. (Unafflilated voters, who now make up almost 45 percent of the electorate, can choose to vote in either primary on Election Day.) Even in Manchester and Nashua, the state’s two biggest cities, more people voted on the Democratic side, and polls suggested that McCain did much better among independents than among registered Republicans. But in 2008, the last time that both parties had competitive primaries, the Democrats attracted more voters in nine of the 10 counties. (McCain won again, but this time he ran as a more orthodox conservative and ran about the same among registered Republicans and independents.) Relatively moderate candidates such as John Kasich need some of those independents to come back in order to do well in 2016.

In Southern states, there has been an opposite trend: as more and more independents identify with the Republican Party, turnout in Democratic presidential primaries has dropped, pretty much removing the chances for a moderate to win those contests.

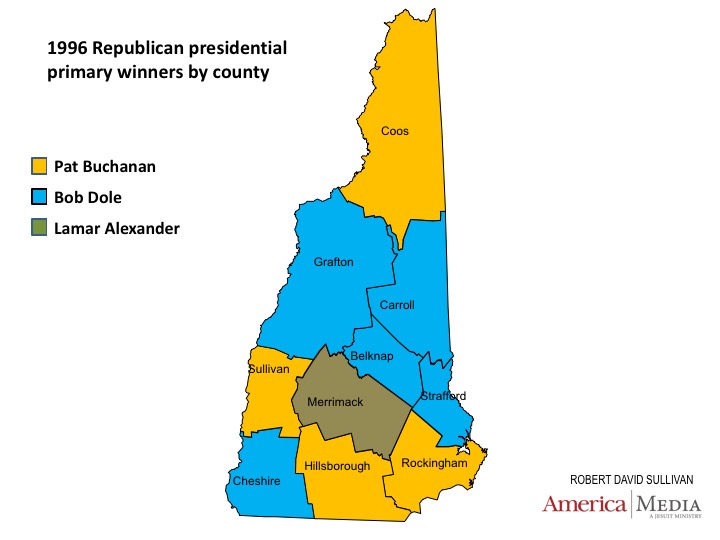

In 1996, Pat Buchanan won his first and only presidential primary in New Hampshire, getting 27.3 percent to Bob Dole’s 26.2 percent, Lamar Alexander’s 22.6 percent, and Steve Forbes’s 12.2 percent. Buchanan achieved his narrow victory by carrying both the highly educated, high-income counties of Hillsborough and Rockingham in the south and the remote, economically struggling Coos County in the north. In fact, most of his margin in Hillsborough came from the mill city of Manchester, and he lost the more affluent city of Nashua to Dole. Buchanan did win pluralities in the southern bedroom communities of Derry, Hudson, Merrimack, Pelham and Salem (by one vote), but in all cases he was well behind the combined votes for the more “establishment” Dole and Alexander. Of course, Donald Trump is facing twice as many establishment candidates in 2016, so he may pull off a win that looks very much like Buchanan’s.

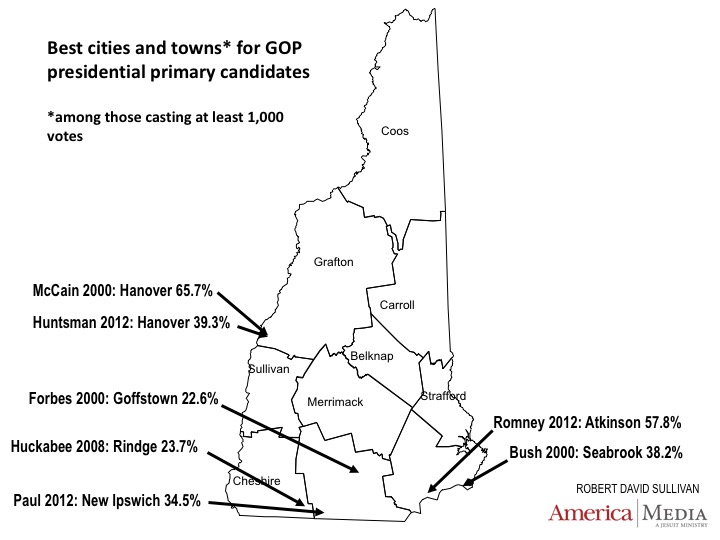

Where did recent Republican candidates run best? Looking only at cities and towns that cast at least 1,000 votes in each GOP primary, we see that the college town of Hanover is pretty consistently the best community of significant size for the most moderate candidate, whether John McCain in 2000 or Jon Huntsman in 2012. But will Bernie Sanders pull Hanover’s independents to the Democratic primary this year? Steve Forbes in 2000, Mike Huckabee in 2008, and Ron Paul in 2012 all did best in towns a bit beyond the heaviest concentration of Massachusetts natives, while Mitt Romney in 2012 did best in towns closest to Boston. In 2000, George W. Bush got only 30.3 percent statewide against McCain, but his totals were more respectable in a handful of towns, such as Seabrook and Rye, that are near the coast (and near the Bush family compound in Kennebunkport, Maine). Will those towns give Jeb Bush an edge in 2016, or has he strayed too far from his family’s New England roots?