One reason for the unenthusiastic coverage of next week’s elections is that polarization has eliminated much of the drama in American politics.

This means party-line votes in Congress, with almost no overlap between Democrats and Republicans. It means that despite rising numbers of voters declaring themselves to be independent, election results indicate that very few Americans vote one way for president and another way for lower offices. The Pew Research Center reports that "ticket-splitting reached an all-time low in 2012 with only 13% of voters selecting a different political party for the U.S. Senate than the U.S. House." Polls indicate that the “swing vote,” consisting of people who entertain the option of switching back and forth between parties, is down to about one-sixth of the electorate.

Some associate polarization with a coarsening of civic behavior. In Iowa in September, former president Bill Clinton sorrowfully said of his countrymen, “We don’t want to be around anyone that disagrees with us.” No doubt plenty of Republicans rolled their eyes at Clinton offering himself as a source of political morality. NBC News’s Mark Murray writes, “the country looks and sounds more like the Divided States of America,” and he quotes Charlie Cook: “Politics has become more bitterly partisan and mean-spirited as I have seen in 30 years of writing a political newsletter.”

But there is no consensus on the causes of polarization. The near-disappearance of the middle ground in electoral politics is something like the steep drop in crime rates since the early 1990s. There are many possible explanations, and they each have their … well, partisans.

In advance of the 2014 midterms, here is a by-no-means-comprehensive guide to reasons for another terrible, dispiriting election season. None involve lead paint.

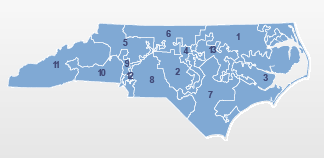

1.) Gerrymandering. One theory is that voters are largely victims of the increasingly sophisticated ways to redraw legislative districts. The idea is that the party in control of a state packs as many opposition voters into as few districts as possible, thereby creating a larger number of “safe” districts for itself. Independent and moderate voters end up holding little power, since the outcome of almost all the legislative races are preordained by the shapes of the districts, and the most partisan candidates get sent to Washington.

This theory became quite popular last year, when an impasse between President Barack Obama and the Republican House led to a temporary government shutdown. Here was Daniel Gaynor on CNN.com:

Gerrymandering has major ramifications for America. It leads to partisan, recalcitrant, and often more extreme voting blocs. And it’s why we have a government shutdown today. Here in Washington, a Tea Party faction of the Republicans—and to be clear, certainly not all Republicans—are so adamant about defunding a law (The Affordable Care Act or “Obamacare”) that they have stopped the government from approving spending. […] The Tea Partiers mostly come from heavily conservative districts, meaning they will have constant support at the polls. These districts, more often than not, come as a result of gerrymandering.

But most political scientists hate this theory, or at least think it’s overblown. For one thing, the U.S. Senate has also become polarized, and it has no districts (just state lines). And it doesn’t explain why, though most congressional seats have been “safe” for one party or another for decades, centrist candidates have only recently fared so poorly in primaries.

2.) Self-segregating voters. Many critics of the gerrymandering theory argue that Americans are creating more lopsided congressional districts by moving to areas with like-minded voters. Thus, Democrats are attracted to urban, culturally liberal areas and Republicans move to exurban and rural communities that are suspicious toward big government. At the statewide level, think of Scott Brown, the former Republican senator from Massachusetts, moving to New Hampshire to attempt a comeback. The result is that each party is getting stronger and stronger in its geographic base.

One piece of evidence for the “sorting” theory is a decline in the number of competitive counties in presidential elections. The New York Times’s Nate Cohn calculated that only 18 percent of U.S. counties—whose lines are not redrawn every decade—produced victory margins of less than 10 percentage points in the 2012 election, down from 38 percent in 1996 and 26 percent in 2000. (Obama won overall by about four points in 2012.) I wrote about this phenomenon back in 2008 for the Boston Globe; in that year, 26 percent of all voters lived in competitive counties, down from 46 percent in the Carter vs. Ford race of 1976.

Cohn elaborates: “More than ever, the kind of place where Americans live—metropolitan or rural—dictates their political views. The country is increasingly divided between liberal cities and close-in suburbs, on one hand, and conservative exurbs and rural areas, on the other.” (For a graphic representation of this trend, see the chart below by software developer Dave Troy, who reports: “98% of the 50 most dense counties voted Obama. 98% of the 50 least dense counties voted for Romney.”) In 2012, Obama got 91 percent of the vote in the Bronx and in Washington, D.C.; Romney got more than 90 percent in 12 rural counties in Idaho, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Texas, and Utah. Voters in these places may not have any acquaintances in the “other” party.

Still, the sorting theory isn’t sufficient to explain partisanship on Capitol Hill. We haven’t reached the point where gated communities are big enough to have their own congressional districts, and most states are too big and complex to be defined by the outlying wing of a single party. In 2013, Gallup found only one state (Wyoming) where a majority of adults identified as conservative and no state where a majority identified as liberal. You don’t expect a Tea Party candidate to win in Manhattan, or an Occupy Wall Street sympathizer to win in West Texas, but you would expect centrist candidates, or party mavericks, to be more successful in such places. (New York City did elect Republican mayoral nominees in five consecutive elections from 1993 through 2009.) They just can’t make it through party primaries anymore.

3.) Genetics. DNA is used to explain everything else, so why not election results? Last week the New Republic’s John Judis reported on the new field of genopolitics, which uses genes and neuroscience to explain “why some people are liberal and others conservative; some people turn out to vote; and why some people favor and others oppose abortion and gay rights.” The idea is that conservative attitudes are associated with caution and pessimism, while liberals are not as strongly attached to tradition and are less fearful (or, if you prefer, more reckless).

What caused such a deep divide between the two viewpoints in the United States? Researchers of genopolitics “argue that the divide is perpetuated through ‘assortative mating’ in which individuals seek out spouses with the relevant political genes and then perpetuate them. The political divide is then transmitted over generations through genetic inheritance.”

This theory complements the ideas that voters are self-segregating by geography. If you have traditionalist values, you probably won’t look for a spouse in San Francisco, and if you want a multicultural environment for your children, you’re not likely to settle in rural Nebraska.

But Judis is bothered by the fuzzy definitions in this young scientific field, which suggest that researchers are conforming to, rather than explaining, the current red vs. blue division in America:

The researchers say that the conservative phenotype includes a “yearning for in-group unity.” But for this formulation to work, this group can’t be a union, and must be something like a church congregation. But the church congregation can’t be that of black Pentecostal church whose members are loyal Democrats, but a white evangelical megachurch. Similarly, if the “suspicion of outgroups” is to define a conservative phenotype, it must apply to suspicions of immigrants, but not of corporate CEOs, rightwing thinktanks, or billionaire oil barons.

4.) The media. Political polarization seems to have intensified since Fox News, and then MSNBC, pursued cable-news audiences with unapologetically partisan programming. So one theory is that voters are walling themselves off from different points of view, getting all their political news from sources like Fox’s Sean Hannity on the right and MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow on the left. (A complementary theory is that voters are getting infuriated by the funhouse version of the opposition party they see on their favored channels. “Popular websites on both the left and the right exist solely to help rile up their readers over the other side’s wrongness,” writes New York magazine’s Jesse Singal.)

A survey by the Pew Research Center, with results released last week, seemed to confirm this idea. “When it comes to getting news about politics and government, liberals and conservatives inhabit different worlds. There is little overlap in the news sources they turn to and trust,” wrote the study’s authors. They found that conservatives are “tightly clustered” around one news source (Fox News), while liberals depend on a variety of sources including NPR and the New York Times. “Amid unprecedented access to information, our fellow citizens are self-segregating themselves into separate political realities,” wrote the Daily Beast’s John Avlon in reaction to the study.

Still, it’s not clear whether the partisan media is a cause or consequence of polarization. In the New York Times’s Upshot website, Brendan Nyhan pointed to other data showing that “most people tended to visit a relatively balanced and centrist set of websites” and that people with wide social networks eventually follow people outside their ideological comfort zone. “Encountering differing views online may encourage people to broaden their information stream,” he writes.

As for the Pew study, Nyhan speculates, “liberals or conservatives may be prone to exaggerating their exposure to ideologically consistent news outlets. Naming Fox or MSNBC in response to a question like the one Pew used may thus be more of a marker of tribal affiliation than a direct measure of news consumption.” Chicken, meet egg.

5.) Campaign financing. This one is pretty straightforward. The cost of running for office keeps going up, and candidates are becoming increasingly dependent on ideologically motivated contributors, many from outside their districts. Centrists may be popular with voters, but they’re not so popular with liberal millionaires in New York, or with special interest groups like the NRA, who want unwavering fealty in return for their contributions.

The Center for Responsive Politics reported this week that almost $4 billion will be spent on campaigns this year, a record for midterm elections. CRP notes an “explosion” in outside money, with PACs and other groups not directly controlled by candidates spending $19.4 million per day in the final weeks before Election Day. Last week, the Boston Globe’s Jessica Meyers reported on the effects of “dark money” (i.e., groups with secret donors that do not coordinate with candidates and can spend unlimited amounts of money, thanks to the Supreme Court’s Citizen United decision). She found that outside spending contributed to a particularly divisive election year: “While vitriolic ads are hardly new, voters this year have witnessed an indundation. Nearly three quarters of Senate ads in a two-week period between August and September showed a candidate in a negative light.”

6.) Disappearing housewives. In a September post (“How women invented grass-roots politics (twice)”), I mentioned a study that found up to 40 percent of all campaign volunteers during the 1950s—a high point for bipartisanship or political wishy-washiness, depending on your view—were housewives. This did not last, and housewives now make up less than 10 percent of canvassers and telephone pests. As Seth Masket writes, “many housewives began to enter the workforce in the 1960s and ’70s and had less time for campaign volunteerism. They were slowly replaced by a more ideologically driven set of volunteers.”

It’s possible that married women are more supportive of centrist or less confrontational candidates. The larger point is that citizen activists have lost influence as mercenaries have discovered the big money being thrown around by campaigns for scripted phone calls to voters, staged events with paid attendees, and the like. Unlike local volunteers who may have an interest in keeping things friendly among neighbors, the professionals are being paid to do whatever it takes to win.

7.) Weak parties. This one is counterintuitive, but it’s similar to the disappearing housewives theory in blaming the Electoral Industrial Complex. The gist is that legislators win election with little help from their political parties; instead they build individual power bases with the help of the big contributors and professional strategists mentioned in some of the above theories. The result is that legislators have little interest or incentive in working with party leaders to break a gridlock and pass meaningful laws.

New York University professor Richard Pildes explains:

My suggestion is that, if we are looking for solutions, we should re-define the problem of effective governance in our era as one of political fragmentation rather than one of political polarization. By fragmentation, I mean the external diffusion of political power away from the political parties as a whole and the internal diffusion of power away from the party leadership to individual party members and officeholders. It is political fragmentation that makes it that much more difficult, in a political world that rests on polarized parties, for party leaders nonetheless to engage in the kinds of negotiations, compromises, and pragmatic deal-making that enable government to function effectively, at least in areas of broad consensus that government must act in some way (budgets, debt-ceiling increases). And because of political fragmentation, party leaders in all our political institutions have less capacity to play this kind of leadership role than in many previous eras.

Do President Obama and Republican House Speaker John Boehner fret about this theory as they share drinks behind closed doors?

8.) The decline of civility. Maybe the problem is that Obama and Boehner don’t get together for bourbon and branch water. A rather inside-the-beltway theory holds that polarization on Capitol Hill can be blamed on a lack of personal interaction among members of opposite parties. Where congressmen once drank and played golf together, they now spend most of their time on fundraising and on trips to their home districts, fearful of losing their seats if they are seen as Washington “insiders.” This leads to bitterness and distrust toward colleagues on the other side of the aisle.

But New York magazine’s Jonathan Chait is disdainful toward this theory, arguing that it overlooks the many strong incentives for today’s partisan behavior (see the other items on this list): “Washington is awash in nostalgic memories of congenial dinner parties and tales of Tip O’Neill and Ronald Reagan knocking back drinks together, and largely blind to the cold rationalism undergirding its current circumstances. The good old days are not coming back.”

9.)The arc of history (bends toward partisanship). Another theory is that the bipartisanship of American politics through most of the 20th century was an aberration, something that can’t be maintained forever in a system that makes coalition governments and power-sharing all but impossible. The Democratic Party in particular spent a long time trying to cover almost the entire ideological spectrum, thanks to its coalition of urban Northerners and rural white Southerners, united by little else by an animus toward “Yankees” (in this case, meaning high-status, mainline Protestants). That alliance slowly dissolved after the civil rights movement, and we’re left with two parties with ideological purity.

Vox’s Matthew Yglesias looked at congressional voting records going back to 1879 and concluded:

During the time when the racial axis was scrambled, the parties were not perfectly sorted around liberalism versus conservatism. A lot of southerners with conservative views on economics were in the Democratic Party for reasons related to white supremacy, and some northerners with moderate views on economics and liberal views on race were Republican.

Now, Yglesias writes, the parties are “cohesive national networks.” (“Even in an extreme case like Alaska, Democrats put forward a candidate who’s more liberal than every single Republican in the Senate.”) This means voters can guess a lot about future behavior from a candidate’s political affiliation—and candidates know not to deviate too much from these expectations.

Perhaps our two parties have finally adapted themselves to a constitutional system that encourages polarization. In that case, the more interesting question is not “Why have politics become so bitter and mean-spirited,” but rather “Why did it take so long?”

More than 70 percent of registered voters and almost 80 percent of likely voters intend to go with a "straight ticket" for major offices this fall, according to the Pew Research Center.