In order to introduce the Catholic Book Club Selection for September, I quote something astonishing from Herbert McCabe’s short collection, Faith Within Reason. It is contained within a brief chapter entitled “Forgiveness.” Reflecting upon Luke’s story of the prodigal son (Lk 15:11-32), McCabe writes:

Sin is something that changes God into a projection of our guilt, so that we don’t see the real God at all; all we see is some kind of judge. God (the whole meaning and purpose and point of our existence) has become a condemnation of us. God has been turned into Satan, the accuser of man, the paymaster, the one who weighs our deeds and condemns us…It is very odd that so much casual Christian thinking should be worship of Satan, that we should think of the punitive satanic God as the only God available to the sinner. It is very odd that the view of God as seen from the church should ever be simply the view of God as seen from hell. For damnation must be just being fixed in this illusion, stuck forever with the God of the Law, stuck forever with the God provided by our sin (155-156).

McCabe understands the essence of the story of the prodigal son not to be the father’s forgiveness of the son, but the father’s welcoming and celebrating the son’s homecoming with a feast. McCabe sees such love as analogous to God’s love for one who has recognized his or her sin:

His [the God of Christianity] love does not depend on what we do or what we are like. He doesn’t care whether we are sinners or not. It makes no difference to him. He is just waiting to welcome us with joy and love. Sin doesn’t alter God’s attitude to us; it alters our attitude to him, so that we change him from the God who is simply love and nothing else into this punitive ogre, this Satan. Sin matters enormously to us if we are sinners; it does not matter at all to God. In a fairly literal sense, he doesn’t give a damn about our sin. It is we who give damns. We damn ourselves because we would rather justify and excuse ourselves, and look on our self-flattering images of ourselves, than be taken out of ourselves by the infinite love of God…Contrition, or forgiveness, is self-knowledge, the terribly painful business of seeing ourselves as what and who we are: how mean, selfish, cruel and indifferent and infantile we are (157).

Lastly, McCabe describes the nature of God’s forgiveness to be something truly surprising:

Never be deluded into thinking that if you have contrition for your sins, if you are sorry for your sins, God will come and forgive you—that he will be touched by your appeal, change his mind about you and forgive you. Not a bit of it. God never changes his mind about you. He is simply in love with you. What he does again and again is change your mind about him. That is why you are sorry. That is what your forgiveness is. You are not forgiven because you confess your sin...You do not come to confession to have your sins forgiven. You come to celebrate that your sins are forgiven (158).

These are not just the words of a thoughtful, loving Dominican priest. These words emerge from a vast technical knowledge of Thomas Aquinas, immersion in analytic philosophy and rigorous theological reflection. These claims about forgiveness find their legitimacy in propositional argument about God’s immutability (God’s nature as unchanging) and God’s providence. Such claims embody something that the most recent papal encyclical on faith conveys about the nature of faith and reason:

Love and truth are inseparable. Without love, truth becomes cold, impersonal and oppressive for people’s day-to-day lives. The truth we seek, the truth that gives meaning to our journey through life, enlightens us whenever we are touched by love. One who loves realizes that love is an experience of truth, that it opens our eyes to see reality in a new way, in union with the beloved. (Pope Francis I, Section 27, Lumen Fidei)

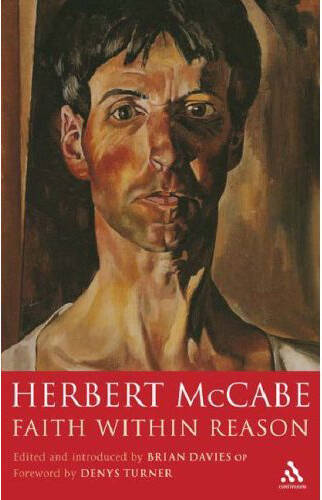

For Herbert McCabe, truth and love converge in the experience and practice of faith. And so, in last months of this year of faith—October 11, 2012 to November 24, 2013—initiated by Pope Benedict XVI, the Pope Emeritus, I urge participants in the Catholic Book Club to reflect on the nature of Christian faith through Herbert McCabe’s short work, Faith Within Reason (Continuum, 2007).

It is the human experience of wonder and surprise that ignites the thought of Herbert McCabe. In the tradition of Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas, the reflective person is one who seeks to know the causes of this or that effect, especially when an event or consequence emerges as a surprise, as unexpected. And so, McCabe, operating in this tradition, can develop an idea about faith. First, God is the thing that God is (and I recognize the term “thing” is quite inadequate for God) because he is uncreated. God cannot create God because God’s definition (again, inadequate) is that God is uncreated. Yet, McCabe argues that God has done the next best thing: God has extended his divine nature to human beings, his creation:

He could not make man by nature divine, but he has given him divinity as gift. This is what we call grace. We do share in the divine nature, we do behave like God, but not by nature…Just as it would be supernatural for a horse to write a poem, so it is supernatural to a human being to behave like God. This means that our divinity must always come to us as a surprise, something eternally astonishing…Now one of the things that sharing in God’s life involves is sharing in his knowledge of himself. This share in God’s self-knowledge is called faith, it is a kind of knowledge that we have not by nature (we could never have it by nature) but as gift (21).

McCabe goes on to conclude that faith is only the imperfect beginning of our share in God’s self-knowledge (21). Faith is what is accessible to humanity through history and revelation (7). Faith is, McCabe writes, “a kind of knowing that God loves us,” but, “it is not just a feeling of happiness because of the beloved…it is what that feeling of happiness is based on” (35). Faith is reasonable and invites further reasoning. Faith is unreasonable in that it demands a certainty that “is not warranted by the reasons” (29).

McCabe’s work is a surprise. It is a thoughtful amalgamation of homespun images, basic human experience, Scripture, Aquinas, modern logic and preaching. Faith Within Reason contains 13 short chapters, some more technical that others, but all interesting and accessible. Please, consider Herbert McCabe and reflect on the following questions:

1. What is the most troubling aspect of faith for you? That is, which element or aspect of the Christian faith seems most unreasonable or unintelligible? Has McCabe’s short work here addressed your puzzlement? Has it helped you to look at such an aspect of faith differently?

2. Are you confronted by others—nonbelievers, skeptics—because of your faith in God? What resources do you consult (or what resources do you draw upon) in order to address intellectually (NOT combat) the claims of non-believers? Is there anything in McCabe that helps enrich such a conversation?

3. How do you nourish your intellectual understanding of faith? How do you consider God’s revelation in a reflective way? What do you use for spiritual reading or the cultivation of your understanding of the Christian faith?

As noted in previous Book Club remarks (The Violent Bear It Away), I have long struggled with questions about violence and what it reveals to us about the nature of human beings and the nature of God . Especially troubling for me is the kind of violence we call ”acts of God”. Can a God who allows innocent lives to be shattered by earthquake, drought, tsunami, plague, famine really be called good? Really? When famine forces a mother to leave one child unburied by the roadside so she can get her second child to a food supply before he too dies, can we say, really, that our heavenly Father is loving?

It is always reassuring to know that stronger souls than I also wrestle with such issues and Herbert McCabe’s meditation on Evil And Omnipotence has provided some reinforcement to the reasoning which--in my stronger moments--lets me say, "Yes, even then he is good; he’s loving."

It is also strangely reassuring when he concludes with these words: “When all is said and done, we are left with an irrational but strong feeling that if we were God we would have acted differently.“ But it is not reassuring at all when he adds, “Perhaps one of his reasons for acting as he did is to warn us not to try to make him in our own image.”