Born in New York City in 1928 as the son and grandson of priests in the Episcopal Church, I grew up in a world in which deeply reverent public worship and devout personal prayer were as natural as eating or sleeping. My introduction to the Roman Catholic Church took place at age 7. My dearly loved Irish nurse, who joined our family a year after my mother died, took me one evening to her parish church for the public recitation of the rosary. A young priest was in the pulpit, bawling at the Queen of Heaven, reciting the Hail Mary at the top of his voice at breakneck speed. The congregation answered at the same tempo, with no attempt at prayer in unison. My 7-year-old soul was traumatized.

For close to 20 years that was my image of the Catholic Church: a place devoid of reverence and where worship consisted simply of spinning the prayer wheel. To this day the public recitation of the rosary sends me up the wall. I can pray the rosary myself only when driving or taking a walk.

When later I started to attend Mass in Catholic churches, I encountered the same bleak scene. Fifteen- and even 12-minute celebrations of the rite, which was considerably longer than today’s ordinary form Mass, were frequent. The Mass was almost entirely silent. The few spoken parts were so garbled that they might as well have been in Mandarin. When the priest reached the prayers at the foot of the altar at the end of Mass, he was often speaking so fast that one often did not realize until well into the first prayer that he had shifted from Latin to English.

Nor was my experience unique. Here is what Avery Dulles, S.J., who became a cardinal near the end of his long life, wrote about his conversion in A Testimonial to Grace (1946):

If there be anyone who contends that in order to be converted to the Catholic faith one must be first attracted by the beauty of the liturgy, he will have me to explain away. Filled as I was with a Puritan antipathy toward splendor in religious ritual, I found myself actually repulsed by the elaborate symbolism in which the Holy Sacrifice is clothed.... There was little external unity to be discerned. The priest, so far from telling the congregation when to sit or stand or kneel, carried out his tasks almost as though he were alone. The congregation, for their part, were not watching with scrupulous exactitude the movements of the celebrant. Some, on the contrary, were reciting prayers on mysterious strings of beads, which Catholics call rosaries. Others were thumbing through pages of prayer-books and missals, which, for all I knew, might have been totally unrelated to the Mass. Not even a hymn was sung to bring unity into this apparently dull and unconnected service.

Unlike Cardinal Dulles, I was never infected with Puritanism, but the pre-Vatican II celebrations of the Mass did nothing to inspire me.

From childhood I had been nourished by a liturgy that fulfilled almost all the postulates of the pre-Vatican II liturgical movement then still suspect in the English-speaking world. Later I would have the privilege of leading the celebration of that liturgy for six years as an Anglican priest. The Elizabethan language we used strikes me now as somewhat stilted, but our Eucharist was deeply reverent. There was full congregational participation. (Catholic references, pre-Vatican II, to the “dialogue Mass” amused us; we knew no other.) And there was fervent singing of hymns, which I shall miss until the day I die. On occasion I heard powerful preaching that moved me then and, in recollection, moves me still.

The Infallible Obstacle

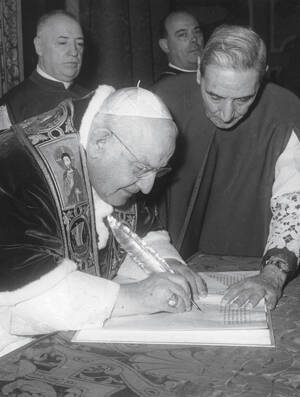

In every Catholic church I entered, in both the United States and Britain, I found tracts with a consistent message: all other Christians are floundering in uncertainty, not knowing what to believe; we, however, have an infallible voice in Rome, who gives us the answer to every question. The reigning pontiff of that day, Pius XII, appeared only too happy to fulfill this role. If this was papal infallibility, I wanted no part of it. The claim to infallibility troubled me. I was unable to reconcile it with my reading of the Gospels. Jesus never gave people answers to every question they proposed. Instead he would enunciate a principle (“Give to God what is God’s, to Caesar what is Caesar’s”) or tell a story (the parable of the good Samaritan, in answer to the question “Who is my neighbor?”) and send people off to work things out for themselves.

On the purely human level I experienced the Catholic Church as a closed, private club, in which nonmembers were not welcome. On an Atlantic crossing aboard the Queen Mary, I attended one of the many Masses celebrated daily in the first-class lounge. I made the Latin responses but did not participate in Communion. The celebrant, the bishop of a Midwestern diocese, encountered me later that day and struck up a conversation. He failed to understand my statement that I was an Anglican seminarian, for he asked whether I was “in” philosophy or theology. I explained that we did not have this division, emphasizing that I was an Anglican.

“Oh,” he responded with obvious displeasure, “but you were answering my Mass.”

“Yes,” I replied, “Our own Mass is much like yours. And I know Latin.”

“Oh,” he snorted angrily, turning immediately on his heel and walking away. I was all of 21.

During my studies at General Theological Seminary in New York, my field education involved shepherding a group of Episcopal public schoolchildren to their religious instruction weekly under the “released time” provision of state law. Waiting with me was always a young Catholic priest, who was there to gather his larger contingent of Catholic children. He invariably crossed to the other side of the street to avoid contact with a heretic. A few years later, after ordination, I experienced similar treatment from a well-known monsignor in Tucson, Ariz., who regularly refused to return a friendly greeting from me or any of the other Episcopal clergymen in town.

On an extended European trip in 1959 I discovered, to my surprise, that the Catholic Church had another face than the one I was familiar with at home. To people I met at the University of Louvain, in Belgium, I explained why I could not accept the pope as some kind of oracle who gives the answer to every question.

“But that’s not what we believe at all,” they told me.

“What then do you believe?” I asked.

They explained that papal infallibility meant simply that when, on very rare occasions, the pope spoke in his official capacity as the church’s chief teacher to define the church’s faith, he would, at the very least, not be wrong. Astonished at this idea, which was novel to me, I reacted with deep skepticism. On the one hand, it seemed something I could accept. But on the other, it seemed to me almost certain that this explanation of papal infallibility was the proposal of some small avant-garde and that it would be only a matter of time before the pope declared them out of bounds, just as Pius XII had rejected the teachings of some of his best theologians in France in his 1950 encyclical “Humani Generis.”

This conversation, and many others I had during that trip (including an audience with a Roman cardinal who spoke almost entirely about his own career) set me on an almost yearlong period of agonizing study, reflection and prayer, during which the question of the church, and my conscientious duty, was not out of my waking thoughts for two hours together. At no time was the Catholic Church, as I experienced it, other than alien and off-putting.

Looking back from the distance of more than half a century, I can see why. The church I confronted closely resembled the one whose demise is loudly deplored by the Society of St. Pius X today: barred and shuttered against the modern world, unwilling to take seriously the possibility that goodness and truth might exist outside its own clearly drawn boundaries.

The interviewer Peter Seewald invited comment on this from Cardinal Ratzinger (Salt of the Earth, 1997):

As a young theologian you complained at the time that the Church had “reins that are too tight, too many laws, many of which have helped to leave the century of unbelief in the lurch, instead of helping it to redemption.” The cardinal replied: “...I cannot recall the individual sentences you cited, but it is correct that I was of the opinion that scholastic theology, in the form it had come to have, was no longer an instrument for bringing faith into the contemporary discussion. It had to get out of its armor; it also had to face the situation of the present in a new language, in a new openness. So a greater freedom also had to arise in the Church.”

When I finally made my decision for that church at Easter 1960, I did so with a cold heart. I found myself, as an Anglican priest, confronted by the question put to Jesus by his critics: By what authority do you do these things? (Mk 11:28). I had no answer. Once my doubts and misunderstandings about Catholic teaching had been resolved, I realized that I could not, in conscience, remain in the Anglican Church. I realized I must act on my convictions, however difficult that might be.

In reality, not all my doubts were ever fully resolved. Deep misgivings remained. To the end, I had nothing more than moral certainty. How could I be sure that the papacy, in practice, was not as Anglicans claimed: the negation of episcopacy; that the Catholic bishops were not mere papal functionaries, with the pope not only the universal but sole bishop? How could I know that the explanation of papal infallibility given me by my friends in Louvain a year previously was authentically Catholic and not the pope-as-oracle doctrine still being trumpeted in pre-Vatican II triumphalist apologetics?

On none of these questions did I ever achieve complete certainty. I just had to make an act of faith, based upon reason but not provable on rational grounds alone, that my doubts had been resolved. Another convert, the late English Msgr. Ronald Knox, wrote once: “In the end the convert is faced with just one question. The Church says: ‘Look into my eyes. Do you trust me?’ All else is irrelevant.”

The Council Opens

Fast forward now two-and-a-half years to the opening of the Second Vatican Council in October 1962. I was teaching at a German Gymnasium, or “higher school.” With faculty colleagues I looked forward eagerly to the weekly radio reports on the council by the Swiss Jesuit Mario von Galli. With astonishment, but with mounting joy, I learned that “the church that never changes” was in fact changing. Still clearly remembered is something Father von Galli told us that, though insignificant in itself, showed that the ice was breaking up. There were council fathers, he told us, who were agitating for a new dogma about St. Joseph (of all people and things)! Pope John XXIII, in a telling move, responded by simply inserting the name of St. Joseph into the canon of the Mass, previously considered untouchable.

At Easter 1965 I started doctoral studies at the University of Münster. Unforgettable, and no less thrilling than Father von Galli’s reports, were the lectures in which the Rev. Joseph Ratzinger related the events in which he himself had just participated in Rome. The more open view of the church, held only by a small and, in the English-speaking world, deeply suspect minority at the time I made my decision in 1960, was being declared authentic. I felt like a man who has bet the ranch on a dark horse and seen him come home a winner. Those were heady days indeed.

Am I happy about everything that has happened in the church since the opening of Vatican II 50 years ago? Of course not. There has scarcely been a council, John Henry Newman said following the First Vatican Council, without great confusion afterward. Mass as a happy-clappy celebration of human togetherness, clown Masses, desacralization taken to the extreme, pulpit messages consisting of little more than “I’m O.K., you’re O.K.” and much else that followed in the decades after the council’s close in December 1965—all that is as deeply offensive to me as the 12-minute pre-Vatican II Masses that helped keep me out of the Catholic Church over a half-century ago.

I rejoice, however, at Vatican II’s discovery that tradition reaches behind what John W. O’Malley, S.J., has aptly called “the long 19th century.” Tradition extends over two millennia and is richly varied. What Vatican II called “the house of God,” a term, once common, rediscovered during the council in the church’s attic and brought into regular use again, is far larger and more roomy than we previously assumed. The most recent evidence of this roominess is Pope Benedict XVI’s establishment of Anglican ordinariates, which allow Anglicans already one with us in faith to enter God’s house, bringing with them their treasured liturgy and spirituality.

Years ago Cardinal Ratzinger told an interviewer, “The only really effective case for Christianity comes down to two arguments, namely, the saints the church has produced and the art which has grown in her womb.” Urgently needed today is deeply reverent, prayerful celebration of the liturgy given to us by the church. We need also to repair the devastation wrought by the musical iconoclasm of recent decades. And we need doctrinally sound preaching, inspired and permeated by Scripture, that joyfully and enthusiastically proclaims the good news of the Gospel: that God loves sinners with a love that will never let us go. These are the elements, I learned as an Anglican well over half a century ago, that constitute “the beauty of holiness, and the holiness of beauty.”

However, I don't have the blind faith in institutional tradition that Rev. Hughes has. That tradition, however well intended and often life-affirming, has also included the "Catholics only" exclusionary mentality for many centuries, along with anti-Semitism (much of that coming from the Gospel of John) which was only publically rejected by John Paul II. In addition, the tradition also includes the concept of "Jesus only" as Divine, instead of thinking that Jesus as a (truly remarkable) Jewish fellow realized the oneness of ALL humanity with the Divine, and that it was only a matter of time until we all "woke up" to that Oneness ourselves as part of a transformation from the inside which would take us to a state of utter love for all humanity and the Creation. Jesus hinted at that himself by saying (we think..., since the Gospels themselves were written by human beings of their day) that ultimately (over many generations?) we, too, could do "these same things, and even more." We have been defined too long by "right belief/theology" instead of seeking the existential/communal "Kingdom of Heaven" within/among which would enpower us to love with no bounds (Mt 5:43-48), just as Jesus did. To put it another way, I seek the religion OF Jesus instead of a religion ABOUT Jesus (although institutional religion need not be discarded, only reformed). It has helped me personally to reflect upon 1) Jesus predicting a future new way of life in his dialog with the woman at the well in John's gospel; and 2) the fact that the Buddha taught the Parable of the Prodigal Son (albeit in culturally different language) 500 years before Jesus, which tells me that the Divine call reaches from within to people across all religious boundaries.

Later in life, we began a search for a "real" Church as Father Hughes describes. We found after many tries, in 1988, Old St. Joseph's in downtown Philadelphia. Ironically we arrived on the 150th anniversary of the third church of OSJ. That was a celebration - all stops out. It was a wonderful Eucharistic celebration, great music, great homily (Walter Burkhart, SJ) and a great congregation. God always likes to play with me. We walked out of the Church that morning saying we are "home". It's a 45 minuter ride to church and all of its multitude of activities. This Summer we will move into the city, primarily to be closer to OSJ. A really good reason for us to do so.

Given the issues in Philadelphia we have also been blessed with "new" Archbishop Chaput, He is open and above board, slogging through a few decades of inept leadership. Philadelphia is on the upswing we hope.

We are "home" at OSJ and maybe even now in the Archdiocese of Philadelphia. and we that much better for finding our home and hopefully with an invigorated diocese.