The Second Chance Act, signed into law in April, represents one of the few glimmers of light in the darkness of the U.S. prison system. Its purpose is to assist prisoners who, on completing their sentences, leave prison with little more than their meager belongings and a small sum of money to take them to their next destination. Half of them will return to live behind bars once again on new charges, in large part because little is given them in the way of help with jobs, housing, mental health care and drug therapy. The new legislation is an attempt to begin changing that grim picture.

Over two million men, women and juveniles fill our jails and prisons. Their numbers have increased six-fold over the last three decades. The United States now incarcerates 762 people per 100,000 of population, more than any other country in the world. European countries in general have far shorter sentences, even for crimes as serious as rape and murder.

The cost of maintaining the nation’s jails, prisons and juvenile facilities has taken a heavy toll on other more positive forms of public spending, especially in the area of education. A recent report by the Pew Center notes that five states spend more on corrections than on higher education: Connecticut, Delaware, Michigan, Oregon and Vermont. Building and operating incarceration facilities has become a major industry in itself.

Having served their time, former prisoners often emerge with little education and few prospects for leading a stable life. Race, moreover, continues to play a troubling role. Recently released reports by Human Rights Watch and The Sentencing Project have found that African-American men are far more likely to be re-arrested and sentenced to prison for drug offenses than are whites. In addition, incarceration rates have also been rising for African-American women.

Introduced in 2004, the Second Chance Act languished for several years until a bipartisan coalition of members of Congress ensured its passage. President Bush himself, in his 2004 State of the Union address, referred to the need for re-entry help for prisoners completing their terms. The services to be provided by the act include education and job training, along with mental health care and drug treatment both during and after incarceration. Drug offenses account for a large proportion of those behind bars, both in state and federal facilities. Also included are mentoring initiatives and support programs for the children of incarcerated people—who, with one or both parents behind bars, are at heightened risk themselves of eventual incarceration.

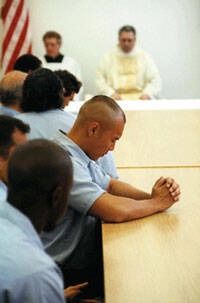

The legislation authorizes $362 million in grants to local governments and nonprofit organizations. Given the scope of the problem, the amount is small, but it is at least a beginning. The next crucial step, however, is to see that the funds are disbursed. Some advocates fear that there may be no disbursements this year or even in 2009, and the act is authorized only through fiscal year 2010. In the meantime, however, private groups have initiated programs of their own. One such initiative is the Welcome Home program in the Archdiocese of Washington, D.C. Begun with modest funding from foundations and other sources, Welcome Home provides mentors to “walk with” prisoners while still in prison and after their release, offering moral support, tutorial service and practical guidance in seeking employment and supportive services. Such a program could be usefully expanded with additional funds from the Second Chance Act.

As helpful as the Second Chance act could be, its effect will be limited without changes in the mandatory minimum-sentencing laws and three-strike laws that are responsible for locking up thousands of low-level drug offenders for long periods. Legislatures in some states, like Delaware and Rhode Island, have at least made efforts to modify them, though so far without success. Other states have moved toward reforming their approach to parole violators, a major cause of the increase in incarceration levels. Some 800,000 persons are on parole, and parole revocations now represent a third of new prison admissions each year. But now several jurisdictions are looking at ways to reduce parole revocations. Kansas, for example, deals with minor violations by assisting with drug treatment and milder sanctions, like ankle bracelets, rather than re-incarceration.

In the meantime, the Second Chance Act offers hope for lowering the nation’s rate of imprisonment. The act remains on hold, though, until funding is made available. This should be done without delay.