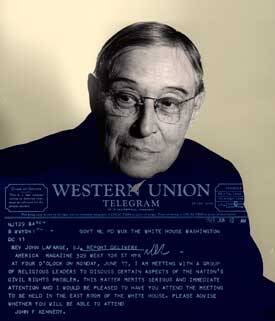

On Nov. 26, 1963, in the church of St. Ignatius Loyola in Manhattan, Cardinal Richard Cushing of Boston spoke before hundreds of mourners of the “three Johns” whom the world needed so dearly and yet had lost in recent memory. The first was John F. Kennedy, 35th president of the United States, who had been assassinated four days previous and whose death the nation was still mourning. The second was “Good Pope John,” John XXIII, who had died that June during the proceedings of the Second Vatican Council. The third, and the real subject of Cushing’s eulogy, was John LaFarge, S.J., a famous pioneer in the field of interracial justice and an editor of America for 37 years, including four years as editor in chief, who had died on Nov. 24, 1963.

Almost every prominent figure in the civil rights movement during those troubled times attended LaFarge’s funeral. They came to pay their respects to an unlikely crusader, a man born of the utmost privilege who by virtue of his long discernment and pastoral experience had come to see racial divides and the long history of discrimination against African-Americans in the United States as the crucial issue of the age.

The Catholic Church in the United States owns a long and complicated history in the realm of race relations, filled with praiseworthy and prophetic moments, but also marked by a long record of discrimination as well as many shameful episodes in which bigotry and ignorance have trumped church teachings and the Gospel message. When the church finally confronted this painful legacy in the 20th century, no name was more closely associated with Catholic efforts for justice for the oppressed than that of John LaFarge, S.J., the fifth editor in chief of America.

A Famous Pedigree

Born in 1880 in Newport, R.I., into an aristocratic and artistic family, John LaFarge held one of the most distinguished surnames in the United States. His father, also named John, was an artist whose works grace many of the most famous churches and museums in the United States. He is remembered not only for his watercolor paintings but also for his extraordinary work with stained glass. John senior was also a close friend of the novelist Henry James and Isaac Hecker, founder of the Paulists. Six years before his death in 1910, he was one of the first seven persons chosen for membership in the newly formed American Academy of Arts and Letters. His sons Oliver Hazard Perry LaFarge and Christopher Grant LaFarge were famous architects in their own right (the latter drew up the original Byzantine design of the Episcopal Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City), and numerous other descendants also became prominent artists. His grandson Oliver LaFarge won the 1929 Pulitzer Prize for his novel Laughing Boy.

John LaFarge, S.J., graduated from Harvard in 1901; but during both his high school and university years he was plagued by poor health, which caused him to take periodic breaks from his studies. LaFarge disliked Harvard, distrusting both the “modernist spirit” of the students and what he saw as anti-Christian attitudes among faculty members, one of whom was the influential philosopher George Santayana. Soon after he matriculated, LaFarge left for Innsbruck, Austria, to study for the Catholic priesthood. In his autobiography, The Manner Is Ordinary, LaFarge wrote of a conversation with his mother upon his departure: “For some reason or other, which neither she nor I could ever explain, she begged me on that occasion: ‘Don’t let them make you a Jesuit.’ I replied, ‘Mother, dear, nothing can ever make me a Jesuit.’ In later years we were somewhat mystified over this.”

Four years later, LaFarge recanted, traveling from Austria to Rome to seek permission to enter the Society of Jesus. LaFarge’s inspiration for becoming a Jesuit, he wrote later, emerged during his annual retreat as a seminarian, as he meditated on the material poverty of Jesus: “The idea of being a priest and of not sharing the poverty of the great High Priest seemed to me intolerable.” Because of his high social standing in this country and abroad, LaFarge’s petition was accepted personally in Rome by Luis Martin, S.J., the superior general of the Jesuits. He was ordained a Catholic priest in Innsbruck on July 26, 1905, and entered the novitiate of the Jesuit’s Maryland-New York Province later that year.

Early Influences

LaFarge originally wanted to go into academia, but his recurring episodes of poor health gave his Jesuit superiors pause; chief among their concerns was that LaFarge would work himself to death. Anthony J. Maas, S.J., LaFarge’s local superior when he was completing the Jesuits’ ordinary program of studies, put their thoughts in stark if colorful terms: “You have the choice of being a live jackass or a dead lion.” Instead of being sent to graduate studies, LaFarge was assigned to work in various parishes as an assistant pastor.

After a number of short-term assignments, LaFarge was sent in 1911 to St. Mary’s County, Md., a rural area with a racially mixed population (including a large number of impoverished African-Americans descended from the area’s slaves) where the Jesuits had first established mission churches in 1634. The Jesuit history with African-Americans in southern Maryland was not without its shameful side; for many years the Jesuits had themselves owned a number of slaves. Fewer than eight decades earlier, the Society of Jesus had sold off its slaves upon orders from Jesuit superiors in Rome.

LaFarge’s work with the local African-American population affected him deeply and shaped many of his attitudes toward race relations. In the “long years of country missions,” LaFarge publicly decried the many obstacles facing both his parishioners and the Jesuits serving them: rural economic survival, how to evangelize and preach properly to interracial populations, the issue of community life in a racially prejudiced society and how to promote education for the poor, among others. These themes set the stage for his later interests in racial desegregation and interracial dialogue.

In 1926, LaFarge established the Cardinal Gibbons Institute, an industrial school for African-American boys in southern Maryland. Despite “a disheartening obstacle of general public indifference to anything connected with the South or the Negro,” LaFarge claimed “tremendous interest in the whole idea of a project that was national in scope, the first national project undertaken by Catholics on behalf of the Negro.” The school struggled from the beginning, hurt both by the financial catastrophes of the Great Depression and the indifference of many Catholics, but the community leaders whom LaFarge encountered would remain with him in various projects throughout his life.

Coming to America Magazine

In 1926, LaFarge left southern Maryland to join the staff of America, then under the direction of editor in chief Wilfred Parsons, S.J. The assignment radically changed the scope and nature of LaFarge’s work, as he became ever more prominent in the world of writing and public speaking. While he did not entirely leave behind his previous interests, retaining close ties to the Catholic Rural Life Movement and remaining in constant touch with his colleagues from Maryland, America would be the primary outlet for his advocacy for the rest of his life.

LaFarge began writing and speaking on interracial dialogue and racism almost immediately. In 1934 he founded the Catholic Interracial Council of New York, which included among its goals the elimination of ignorance regarding race issues, social justice on the model of the old Catholic Action movement and a struggle against Communist inroads. By 1960, there were 42 Catholic Interracial Councils around the United States, and they joined together as the National Catholic Conference on Interracial Justice in 1959. In later years, Catholic Interracial Councils gained popularity with political activists as an avenue for interracial dialogue, and gained much publicity in the 1960s for their popularity with college students.

In 1937, America Press published LaFarge’s most important book on race relations, Interracial Justice: A Study of the Catholic Doctrine of Race Relations, which emerged out of his philosophical education as well as his experiences in Maryland and New York City in the 1920s and 30s. The book laid out a lengthy argument for rethinking American racial attitudes, particularly racist attitudes that blamed the relative lack of African-American intellectual or economic achievements on a supposed inferiority. LaFarge attributed this apparent disparity to the economic and cultural impoverishment that African-Americans had suffered at the hands of the ruling classes in America since their unhappy arrival.

Using his training in philosophical Thomism, LaFarge argued that human rights were natural to all people regardless of race, class or creed; the rights of individuals were not bestowed by governments, but were merely protected by them. The U.S. Constitution “is not the source or origin of our natural rights,” LaFarge argued. “It is the governmental instrument by which the national sovereignty guarantees…those natural rights which the citizen enjoys by virtue of the very fact that he is a citizen and as such is vested with certain rights as he is bound by certain duties.”

This argument impressed an unlikely reader, Pope Pius XI, who in 1938 asked LaFarge to help write an encyclical on racism, to be titled “The Unity of the Human Race” (Humani Generis Unitas). Pius had been impressed by the portability of LaFarge’s natural law argument, which could be applied to any society’s racist policies, including those of Nazi Germany. The encyclical was never released, however, and only years later was its existence and LaFarge’s participation in its composition confirmed.

Despite his opposition to interracial marriage (because of the social damage he believed it caused children), LaFarge also made a strong case for the immorality of American segregation on practical grounds, saying that when mandated it “imputes essential inferiority to the segregated group,” and actually would end up hurting the groups enforcing it by depriving them of the cultural and economic benefits of free exchange. This approach exemplified LaFarge’s primary strategy throughout his career, combining philosophical and religious reasoning with practical, politically sensible approaches to social ills.

LaFarge became executive editor of America in 1942 and editor in chief in 1944; he established during his tenure the progressive editorial tilt that the magazine has retained in large degree to this day. As he readily admitted, he was not a skilled administrator, and after four years LaFarge stepped down as editor in chief, while remaining on staff as an associate editor. He continued to write extensively on race relations, but also contributed his thoughts regularly on labor, foreign affairs, McCarthyism, Catholic liturgical debates and countless other issues.

His influence on the civil rights movement began to decline in the 1960s as the movement benefited from the emergence of African-American leaders and took on a more assertive tone at odds with LaFarge’s more conciliatory approach. Still, LaFarge’s prominence in the movement earned him a spot on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial behind Martin Luther King Jr., during his famous “I Have A Dream” speech in August 1963.

In addition to his many books and his contributions to America, LaFarge also wrote for countless overseas periodicals as well as for such American reviews as Commonweal, Liturgical Arts, Sign, Catholic World, Saturday Review and many more. He also wrote over 30 book reviews a year for America, as well as for The New York Times, Saturday Review, Thought, Interracial Review and the Herald-Tribune.

Early Ecumenism

While most famous for his work on race relations, LaFarge was also a great champion of interfaith and ecumenical dialogue, though his work in this area was often stymied by the attitudes and policies of his own church. Longstanding Catholic concerns over “indifferentism,” the acceptance of relativist approaches to the truth claims of different religious traditions, made it difficult for Catholics of his time to receive permission to appear in public with rabbis or Protestant ministers. Furthermore, a long history of anti-Catholic bigotry on the part of various U.S. Protestant denominations, which in a few cases continues into the present day, hindered any significant ecumenical efforts. LaFarge’s gentle pressure on bishops and Catholic organizations to reach out to other faiths and Christian denominations nevertheless continued for years, and finally found some fruition with the ecumenical and interfaith reforms of the Second Vatican Council.

Ever practical, LaFarge viewed interreligious and ecumenical dialogue not in solely theological terms, but as a practical interfaith response to external threats. “If we Catholics are not to be completely isolated in the battle against atheism and paganism and their attendant evils,” he wrote in 1942, “we cannot conduct the battle alone.” The progress made on issues of interfaith and ecumenical dialogue in the past few decades can be attributed in many cases to seeds that LaFarge and his colleagues planted in the 1940s and earlier.

Criticisms

Not all of LaFarge’s peers and later biographers found his efforts and attitudes to be without blemish. Recent historians have argued that for all his progressive ideas on race, LaFarge (like other white pioneers for racial justice) was often unaware of his own paternalistic attitudes, particularly when it came to including African-Americans in structures of authority or recognizing the urgency of the racial crisis facing the nation at the time. LaFarge was also capable of allowing his fear of Communism to color his ideas on race, to the extent that he sometimes seemed to promote interracial activities as a way to counteract Communist infiltration into American minority politics. These tendencies diminished LaFarge’s influence in the civil rights movement in the crucial years of the late 1950s and early 1960s, particularly as he had already reached his 80s before the movement gained real momentum.

Final Days

LaFarge’s last book, Reflections on Growing Old, offered him a chance to comment on his status as something of an elder statesman, both among American Jesuits and among larger circles of social progressives. “Old age is a gift,” LaFarge wrote, “a very precious gift, not a calamity. Since it is a gift, I thank God for it daily.”

LaFarge died on Nov. 24, 1963, soon after that book’s publication, at the age of 84. “He was never one to identify the status quo with the Law of God,” his fellow editors wrote soon after his death, “nor, by the same token, to lose the vision of ultimate and abiding values underlying social change.” A year later, the editors of America announced the establishment of an institute bearing his name that would be dedicated to interracial affairs.

America’s editor in chief at the time, Thurston N. Davis, S.J., wrote of LaFarge’s important influence on the development of the magazine: “Whatever influence [America has] today, what authority we can muster in the world of the press, we owe largely to this gently dogged priest whose broad sympathy for his fellow man spanned the whole world round and constantly spilled over onto our pages.”

Listen to an interview with James T. Keane, S.J.