A Change in Direction

A friend in Philadelphia who is a lapsed Catholic tells me that when Pope Francis paid a visit to her area in September, she spent most of the weekend crying because she was so moved. And she wasn’t even at any of the events. She watched it all on television in her living room in the suburbs.

In New York, a Muslim woman told a radio station that she had spent hours “praying to Allah” that she would catch just a glimpse of Francis as he drove through the city.

This is some of the effect Francis has on people—and not just devout Catholics. Part of the Francis phenomenon is how he is appealing to people outside the Catholic realm too. He is what John Gehring, in The Francis Effect, calls an “unlikely global rock star.”

Gehring is a self-described cradle Catholic who attended Catholic schools from kindergarten through college, served as an altar boy, wrote for a Catholic newspaper in Baltimore and worked for the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. A “social justice advocate,” he currently heads the Catholic program at the Faith in Public Life advocacy group in Washington, D.C.

Gehring delves extensively into the Catholic Church the pope has inherited in the United States. In Gehring’s view, that church has been hijacked by a well-organized movement of right-wing institutions, think tanks and bishops who have abandoned the church’s teachings on social justice. Instead, this movement focuses almost obsessively on the “culture wars” issues of abortion, same-sex marriage and contraception. Lost in the shuffle are the church’s teachings on poverty, social justice and solidarity with the oppressed.

The church’s right-wing movement is somewhat similar to the conservative wave that overtook Washington during the past few decades, starting in the 1980s under Ronald Reagan, at a time when well-financed and effective groups like the Heritage Foundation emerged and helped shift the country to the right.

Francis, of course, is turning all this on its head—or at least trying to—and Gehring meticulously documents what he is up against. He spends more than half the book examining the right-wing “hijacking” of the church, arguing that many bishops and Catholic groups are out of touch with Francis.

He tells the story of how eight months after Francis’ shocking election as pope, the U.S. bishops gathered in Baltimore for the first time as a group since his elevation. Little seemed to have changed for them. The topics were the same: same-sex marriage, contraception, religious liberty. No formal discussion about unemployment, income inequality, poverty, attacks to workers’ rights or the environment.

“It was business as usual taking place against the backdrop of a papacy redefining the Catholic narrative,” Gehring writes. “The memo never made it to Baltimore.”

Gehring argues that some bishops also never got the memo about simple living and a “church that is poor and for the poor” that Francis announced during his first news conference as pontiff. Gehring holds up as one example Archbishop John Myers of Newark. He embarked on $500,000 in “luxury renovations” to a five-bedroom, three-car-garage mansion that he was preparing as his retirement residence on eight acres of land.

In a clear sign of the tensions, some of the bishops have taken verbal shots at the pope. Gehring notes how Bishop Thomas Tobin of Providence, R.I., took to his diocesan newspaper to wonder why Francis hasn’t spoken more about abortion. He also expressed discomfort over the pope’s “free-wheeling style” and “off-the-cuff comments.”

Perhaps the biggest critic of Francis among America’s Catholic hierarchy has been Cardinal Raymond Burke, whom Francis removed from his post as head of the highest Vatican court. In now famous comments, Burke described the Francis-led church as a “ship without a rudder.”

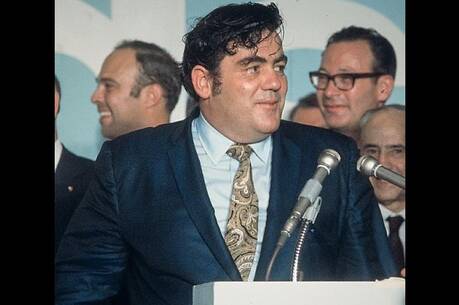

Supplementing these efforts are think tanks, advocacy groups and intellectuals, Gehring asserts. He points to figures like William Donohue of the Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights, who “plays the role of gloves-off street fighter” defending church orthodoxy.

There are intellectuals, like Robert George of Princeton University, publications like First Things, wealthy chief executive officers like Tom Monaghan, the founder of Domino’s Pizza, and think tanks like the Acton Institute, a free-market group based in Grand Rapids, Mich.

Now, arriving just in time, Gehring hopes, are the Francis-era troops. The “Francis era” here officially began with his surprise appointment of Blase Cupich as archbishop of Chicago, the third largest archdiocese in the nation. Cupich declined to live in luxurious quarters. He said no to a $14 million mansion with 19 chimneys, Gehring notes.

Another Francis man, Cardinal Seán O’Malley, O.F.M.Cap., is the pontiff’s top American advisor. O’Malley, who was brought in to clean up the sex abuse mess in Boston, is the kind of humble, transparent leader the pope is looking for. He wears a simple brown cassock and has been seen mowing his own lawn. On “60 Minutes” he called the Pope Benedict XVI-initiated investigation into U.S. nuns a “disaster.” Other Francis men are slowly being put in place.

But as Gehring points out, it won’t be easy. Of 270 active bishops, 232 were appointed by John Paul II or Benedict XVI over nearly 35 years. Francis, already 78, will not serve anywhere near that long. “Change is not likely to come quickly,” Gehring writes.

Gehring’s book was published before Francis’ historic trip to the United States, so the impact of the visit is not assessed. Without a doubt, the pontiff’s unforgettable moments on the East Coast—from Congress to Madison Square Garden to Independence Hall—will help advance his imprint on the American church. His arresting mention of Dorothy Day during his address to Congress could not have laid out more clearly what kind of church he envisions. Whether that will fully happen during his pontificate is difficult to say.

Gehring’s book provides a valuable roadmap to the different forces at play. The book is populated by mini-vignettes of dozens of Catholics—well-known and otherwise—who weigh in on Francis. Because there are so many, the names and stories can get lost in the shuffle, but they give a helpful panorama of the Catholic landscape according to Gehring.

Whether the American church will turn to the one Gehring pines for remains to be seen. But clearly, the battle is on.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “A Change in Direction,” in the February 1, 2016, issue.