The Confrontational Approach

From this evil-smelling spring of indifferentism flows the erroneous and absurd opinionor rather deliriumthat freedom of conscience must be asserted and vindicated for everyone. Pope Gregory XVI’s condemnation of religious liberty in the encyclical Mirari Vos (1832) was still official Catholic teaching at the start of the Second Vatican Council in 1962. True, it was modified in practice. Where Catholics were a minority, religious liberty could be tolerated for reasons of expediency. Where conditions permitted, however, church leaders sought, as far as possible, to shape civil law according to Catholic norms. Error, they insisted, has no rights. This view had powerful exponents at Vatican II, foremost among them the official guardian of orthodoxy, Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani, Prefect of the Holy Office. It was finally reversed in Dignitatis Humanae (DH), the Declaration on Religious Liberty. Approved at the council’s fourth and final session in 1965, DH was one of the major breakthroughs of Vatican II. Though error might have no rights, critics pointed out, people did. One of them was liberty of conscience.

Of course it was not as simple as that. A change so sweeping required long preparation. Mirari Vos had said: Prosperous states have perished through this one evil, the immoderate freedom of opinions, license of speech, and love of novelties. In 19th-century Europe this was a plain statement of fact. There the banner of religious freedom, first raised in the French Revolution, was held aloft by the church’s embittered enemies. Advocates of an all-powerful state, they sought to reduce the church to the status of a closely controlled private club. For them separation of church and state, a cornerstone of their program for human freedom, meant throwing off the shackles of the ancien régime which, under the plea of caring for people’s souls, had laid on them burdens too heavy to bear. Whether people even had souls was a matter of opinion, the revolutionaries insisted. What was certain was that they had minds. And they required neither pope nor prince to tell them how to think and act.

Americans experienced none of this. Here the leading exponent of religious liberty was the American Jesuit John Courtney Murray. The Founding Fathers, he pointed out, were believers all: at least in God, most of them in Christianity. In the United States anti-Catholicism, though strong, came not from the champions of human reason but from Protestants suspicious of Rome and all its ways. The Portuguese Jesuit Hermínio Rico, author of the first book listed above, describes the still continuing difference between New and Old Worlds succinctly: Religion is ubiquitous in all the American political process. In Europe, secularity of the state means a strict laicity, that is, an almost absolute absence of religion or religious references from the political discourse.

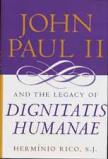

Long before the council, Murray was contending that religious liberty was a great opportunity for the church. Silenced by his Roman superiors in 1954, he found his voice again eight years later, when Cardinal Francis Spellman took him to the council as his theological expert. There Murray became one of the architects of Dignitatis Humanae. In his dense and meticulous study of the declaration, Rico presents also the arguments for religious liberty of a French school, who contended that Murray’s philosophical-political case was inadequate and inserted into the declaration theological arguments rooted in Scripture. The result, like most texts written by committees, satisfied no one completely.

Rico analyzes DH under three aspects (or moments, as he terms them). First was the church’s acceptance of constitutionally guaranteed religious freedom, after a century and a half of resistance, as a basic human right, not to be denied to anyone. Second, DH demanded religious freedom for the church itself, in the face of atheistic Communism. The third aspect, still unfolding, is more complex. It consists, on the one hand, of the challenges to the Catholic vision of the human person, individual and social, by the dominant culture of democratic, pluralistic societies; and, on the other, of the rivalry, within the church, of different views about what is the best approach to respond to those challenges.

The second aspect of DH was of special interest, at the council, to the young Polish bishop Karol Wojtyla. (An auxiliary bishop since 1958, he did not become archbishop of Krakow until January 1964, after the council’s third session.) Though not a major player at Vatican II, five of Wojtyla’s 24 conciliar interventions concerned religious liberty. Fully half of Rico’s book deals with Wojtyla’s use of DH as pope.

The church-state conflict...has been basically resolved, Rico writes. But the central issue of confrontation between Catholicism and liberalism [has] returned under the form of a church-society debate about the place of religious principles and the public role of the church in the formation of a public consensus on the values and rights that constitute the substance of human society. Wojtyla’s conciliar interventions on religious liberty showed no awareness of a need for change on the part of the church. As pope, John Paul has spoken positively about democracy, while warning that tolerance can easily slide into ethical relativism. For John Paul, only a democracy firmly grounded in values can fulfill its objectives and accomplish its professed advantages.

Few democracies today fulfil this postulate. Catholics differ about how to handle this situation. Those who favor dialogue contend that we must look for the elements of truth that always lie at the heart of error. John Paul favors confrontation, epitomized most forcefully in his denunciation of today’s culture of death: abortion on demand and euthanasia.

Rico affirms the pope’s message, but questions his method. Rico asks whether the tone and the intensity of the condemnations and the strategies for promoting alternatives do not, actually, induce less receptivity for the message of the church in society. John Paul slides too easily into a black-and-white analysis, overlooking distinctions and nuance.... These approaches, as rhetorically powerful as they may be, tend to encourage rapid but simplistic judgments with no real grappling with the good intentions and honest critical thinking [of] many people in the middle, both within and without the church. Rico fears that the church is retreating into its own fortress, cutting itself off from the progression of secular culture. This reverses the approach of Vatican II, which sought to understand and engage secular culture, correcting and redirecting it through dialogue but without compromise.

Rico identifies three consequences of the new siege mentality which he sees in the church today. First, tendentiously sectarian and integralist groups [have] the loudest voices. Second, disproportionate importance is given to a particular issue (in the nineteenth century, religious freedom; now, abortion) that becomes the make-or-break criterion of all judgments and the focus of totally one-sided extremist positions. Third, insistent block condemnations of whole movements or ideas do not make any differentiation between basic principles and relative applications.

Throughout the 19th century and into the 20th, this stance weakened the church’s influence on society and drove it into a dead end of doctrinal immobility. Rico sees the church today not at a dead end, but at a crossroads: It is a time of decision between alternative emphases, a time of choice between competing historical and theological inspirations for the church’s social mission.

Rico’s book is important. It is also difficult. The severe demands imposed on the reader by the complex subject matter are increased by the fact that English is not Rico’s native language.

Jo Renee Formicola’s book covers some of the same ground. The author, a professor of political science at Seton Hall University, calls it a series of stories’ about political changes that have occurred because of the influence and efforts of John Paul II. Prescinding from discussion of religion’s proper role in politics (a central theme in Rico’s book), Formicola examines the pope’s efforts to transform society through his personal charisma and what she calls prophetic politics. Formicola ranges widely, from liberation theology in Latin America, through papal efforts for peace in the Middle East to the pope’s efforts to improve the situation of Catholics in China.

Unfortunately, much of her information is misleading or simply wrong. Herewith a small sample. A reference to bishops making ad lumina visits to the pope might be excused as a misprint. She accepts the now discredited charge that John Paul established a secret alliance with the Reagan administration to overthrow Communism. She takes seriously the late resigned Irish Jesuit, Malachi Martin, a world-class confidence artist. She says that the pope replaced the current Jesuit General, Peter-Hans Kolvenbach, with a more conservative leader (not identified). She finds the statement in the encyclical Laborem Exercens that both capitalism and Communism are deficient in their treatment of the individual (hardly novel in papal teaching) quite startling. She misunderstands the Immaculate Conception. She thinks that Archbishop Oscar Romero was shot in his cathedral. And in a passage friendly to Israel she refers to the now infamous Balfour Declaration.

Stick with Rico. But prepare to be challenged.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “The Confrontational Approach,” in the November 18, 2002, issue.