A Master of Metaphor

To understand what St. Paul was saying in his letters, we also need to appreciate how and why he was saying it. Paul’s letters, which are the earliest complete documents preserved in the New Testament, were written to predominantly Gentile Christian communities in the Greco-Roman world. With the exception of Romans, all the undisputed Pauline letters were addressed to communities that Paul had founded. They were intended to deal with problems and questions that had arisen after Paul moved on to found new communities. Paul was basically a pastoral theologian. That is, in his letters he dealt theologically with the pastoral concerns of his beloved converts.

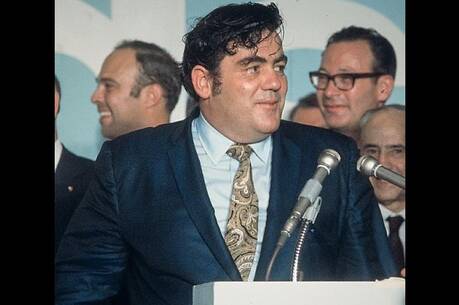

Raymond F. Collins, professor emeritus of religion and former dean of the School of Religious Studies at The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C., contends that Paul was a master of metaphor. He notes that metaphor, like a poem, articulates an affective value, and observes that through his images Paul strove to shape the affective values of those to whom he wrote. Thus he examines how Paul used metaphors in each of his letters to clarify the Gospel for a particular audience and to persuade the various churches about the truth of his message. By exploring how and why Paul wrote, Collins offers a fresh and sound point of entry into what Paul wrote.

One of Collins’s longstanding scholarly interests has been Greco-Roman rhetoric and its influence on Paul’s writings. This concern is manifest especially in his marvelous commentary on 1 Corinthians (1999) in the “Sacra Pagina” series. As a Jew born in Tarsus, Paul was not only initiated into Jewish Scriptures but also exposed to the conventions and practices of classical rhetoric. In addressing Gentile Christians in the Roman Empire, it was natural that Paul would write in ways that would be most intelligible to them. Moreover, since he was writing mainly about God, spiritual matters and the future, Paul had to make abundant use of such figurative language as metaphors, similes, analogies, hyperbole and so forth.

After a brief introduction to the role of metaphor in Hellenistic rhetorical theory, Collins analyzes Paul’s use of images in the seven letters that almost all scholars agree came directly from Paul: 1 Thessalonians, Philippians, Philemon, Galatians, 1 Corinthians, 2 Corinthians and Romans. Also included are a synthetic classification of Paul’s principal images and general observations about his use of them.

According to Collins, Paul drew his metaphors from his Jewish religious heritage, cultural milieu and personal experience. Their major semantic domains are kinship, the body, the senses, life cycles, walking and stumbling, running and fighting, occupations, agriculture, animals, construction, the temple and its cult, finances, social status, public life, the courtroom and the cosmos.

Collins shows, for example, how Paul, in the very short letter to Philemon, used the images of family and kinship, mutual love and finance to persuade the slave owner Philemon to take back his (now Christian) runaway slave Onesimus as “a beloved brother.” Likewise, in his longest and most theological letter (Romans), Paul builds a case first for the universality of human sin, largely with anatomical imagery, and then for the gratuity of God’s grace, mainly with courtroom imagery. Next, Paul uses images of stones and botany (especially the olive tree) to describe the renewal of Israel and the salvation of Gentiles. Then he develops his portrait of Christian life in terms of temple and sacrifice, struggle and clothing. As Collins observes, without metaphors Paul’s letter to the Romans would not be the masterpiece that it is. Paul’s genius was his ability to adapt his imagery to the situations and needs of the people to whom he wrote and to convey to them profound theological truths.

It is sometimes difficult for modern readers to discern the precise meaning of Paul’s figurative language. This is where Collins’s vast learning and pedagogical skill come in. As an expert guide to the Greco-Roman and Jewish literary context, to Paul’s writings and to current scholarship, Collins is able to explain what the images most likely conveyed to Paul’s first readers and what they might signify to readers today.

The Power of Images in Paul is a work of sound scholarship that is also accessible to a general audience. An individual or a Bible study group can use it profitably alongside a careful reading of each letter. Those who do so will become more careful readers of Scripture (since Scripture communicates largely through images) and will encounter Paul in new ways. It provides fresh insights to preachers and teachers working through specific Pauline passages and themes. The various images that Collins treats may also provide abundant material for meditation and prayer. For those in search of a reliable and creative resource during this Pauline year, I recommend this volume with great enthusiasm.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “A Master of Metaphor,” in the November 10, 2008, issue.