Nonviolent Revolution?

What more can be said about the nine American Catholics who on a May afternoon 44 years ago stormed a Selective Service office in Catonsville, Md., seized draft files and burned them in a parking lot while praying the Our Father? Their exploits have been memorialized in songs, poetry, literature, film, visual arts, even board games and, most famously, in the play “The Trial of the Catonsville Nine,” by Dan Berrigan, S.J.

Nonetheless, the story of one of the most iconic antiwar protests of the Vietnam era has been only partially told.

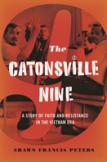

The icon comes to life in this assiduously researched history by Shawn Francis Peters, author of several books on law and religion. Peters consults myriad resources, including the files of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, to tell the story of nine ordinary Americans, the influences that led them to burn draft files at Catonsville, their trial and imprisonment and their life afterward. His equitable coverage of each one provides an important corrective to an antiwar action that is often exclusively associated with the two priests involved, Dan and his brother Phil.

This book, however, is much more than a group biography. A Catholic native of Catonsville, Peters contextualizes the actions of the Nine within the American antiwar movement, Baltimore in particular and a church flush with Vatican II energy.

Peters records with a historian’s rigor and the compassionate curiosity of an investigative journalist. Yet even in this prosaic telling, the Catonsville draft-file burnings stand out as a poetically holy and politically relevant act.

He covers the drama in the courtroom, the daily street demonstrations—pro and con—and the nighttime gatherings at St. Ignatius Church, where heavy-hitters of the peace movement like Dorothy Day and William Sloan Coffin praise the Nine for their “desperate offer for peace and freedom.” Many Baltimoreans are less generous. “I think they ought to lock ’em in the can and throw away the key,” says a popular disc jockey. Amid such a vivid reconstruction of events, the reader feels the chaos and hope of that period.

When legal appeals fail to overturn their guilty verdict, five of the Nine go underground. Peters examines the political and personal consequences of this decision, inspired by the historian Howard Zinn. The civil disobedient, Zinn argues, is under no moral obligation to surrender to authorities and should evade prison to continue the witness. Dan Berrigan’s five months on the lam and the F.B.I.’s high profile search for him keep the Catonsville draft-file burning in the public eye.

But a decade of living as a fugitive takes its toll on Mary Moylan, whose life plunges into a downward spiral. Family members of the Nine tell of the F.B.I. watching their homes, showing up at funerals and, in the case of the Berrigans, lurking outside the hospital room of their ailing mother. Nurses reportedly provided poor care to Frida Berrigan because she had raised “unpatriotic” children. “Oh Jerry, take me out of this hospital,” she begs her son. “They don’t want me here.”

The holiness described here is not the stuff of our fantasies, in which everyone loves serenely and is certain of God’s blessing. As one Catonsville participant, David Darst, puts it, the Nine wanted to hinder the war in “an actual physical way.” It is a Herculean task and they are fragile human beings, encumbered, like the rest of us, with ego, depression, addiction and plain old frailty. The clarity and community experienced during the action and trial give way to the confusion and loneliness of everyday life. Phil’s demanding energy alienates supporters. Dan nearly dies in prison. Moylan later disassociates from a protest she considers too conventional and Darst, who in the courtroom spoke eloquently of “sacred life,” contemplates suicide. Peters’s depiction of the Nine in all their humanness underscores how much their audacious protest at Catonsville was born of faith.

Contrary to popular perception, Catonsville was not a singular act of civil disobedience but part of a continuum in the antiwar protests of the 1960s, influenced by the draft card burnings and a growing interest in targeting Selective Service offices. For Phil and Tom Lewis, architects of the action, the burning of draft files, “death certificates” as Lewis called them, represented a shift in their antiwar efforts from legal protest and civil disobedience to concrete, nonviolent intervention. “What if draft boards didn’t exist?” Phil asks. “How would the government locate military age males?”

Dorothy Day once described the burning of draft files at Catonsville as an act of nonviolent revolution not only “against the state but against the alliance of church and state, an alliance which has gone on much too long.” The raid on Local Board 33 provoked a reckoning with that unholy alliance, a reconsideration of allegiances. While many wished the priests and their cohorts would go back to tending to their flock and “stop their political agitation,” some understood their “burning of paper instead of children.”

I read Dan Berrigan’s The Trial of the Catonsville Nine while at the University of Virginia. A student of social and political thought with an evangelical orientation, I knew nothing about these Catholic radicals and their fiery protest. Berrigan’s slim script shook me to my core. Here were people of faith unwilling to lament and then accept war as inevitable. The times are “inexpressibly evil,” they said, and yet they are “inexhaustibly good” because of those who have the hope to make them so. We think of such people, writes Berrigan, “and the stone in our breast is dissolved/we take heart once more.”

Thirty years later, I remain deeply grateful for the Catonsville protest, its opening of new possibilities for being a Catholic in a country where war-making has become part of the fabric of our lives. To reacquaint myself with people who confronted war personally, to see them in all their contradictions and frailties, as I did reading this book, gives me heart once more.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “Nonviolent Revolution?,” in the November 12, 2012, issue.