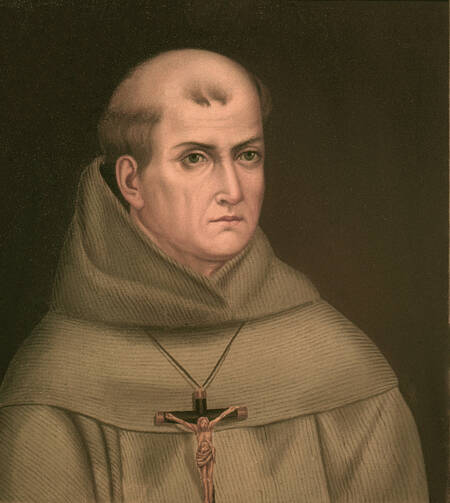

St. Junípero Serra

The most controversial comment made by Pope Francis during his in-flight media conference from the Philippines on Jan. 19 may not have been his aside that Catholic families are not required to breed “like rabbits.” Rather, it may have been the announcement that during his visit to the United States this fall, he would canonize Junípero Serra, the 18th-century Franciscan and missionary to the region that is now California.

Blessed Junípero Serra was one of the many indefatigable missionaries who left their home countries to minister to people who were at the time considered unworthy of such attention by many Europeans. The Spanish-born Franciscan assiduously learned the local languages and underwent immense hardships to bring the Gospel to those whom he clearly loved and cherished. But Friar Serra’s legacy is not without controversy. He is seen by some historians as overly supportive of the Spanish colonialists, who severely mistreated the native people. The perception of missionaries who “forcibly converted” the local peoples is also complicated by their ties to the Spanish colonialists. Father Serra is also quoted as approving of the Spanish overlords’ practice of administering beatings to the Indians because that practice was commonplace. Others argue that he should be seen far more as a protector of Indians, much as the Jesuits were in the Reductions in Latin America in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Junípero Serra was a person of his time. We know the saints were not perfect, but neither are we. Let us pray that he will help us in our own efforts to evangelize, that we may avoid oppressing others and always make known through our lives the freedom of the Gospel.

Nigeria on the Brink

To Western eyes, President Goodluck Jonathan of Nigeria appears extremely vulnerable as he heads into the country’s elections on Feb. 14. His government has failed to recover over 200 of the girls abducted by Boko Haram last spring and in early January the militant group killed hundreds of innocent civilians, perhaps as many as 2,000, in a massacre in the town of Baga. But it is the nation’s complex ethnic, religious and regional divisions that will determine the outcome, not unrrest far from the capital.

President Jonathan’s decision to contest the 2011 election—thus breaking an unwritten power-sharing rule that the presidency alternate between Christians and Muslims—sparked violence that left 800 dead after his victory. With his decision to run again, the threat of similar unrest looms large. Muhammadu Buhari, a Muslim and former military dictator, heads the opposition All Progressive Congress. Running on a credible anti-corruption platform, Mr. Buhari is better placed than any other candidate since 1999 to wrest control from the long-reigning People’s Democratic Party.

Ensuring a peaceful and fair election process is critical. But Nigeria’s leaders cannot wait until the votes are in to get a handle on the war within the country. Boko Haram poses an increasing threat to the region, and calls for outside intervention are growing louder. One Catholic bishop has said that “a concerted military campaign is needed by the West to crush Boko Haram.” It would be better for the United States to follow the lead of African leaders, who announced on Jan. 22 that they would seek U.N. authorization for a multinational force to take on the militants, while stepping up humanitarian aid to the victims displaced by this senseless violence.

Germany’s Challenge

Europe is understandably on edge. In the weeks following the deadly terrorist attacks in Paris, authorities in France, Belgium and Germany have arrested dozens of suspects, many with ties to Islamic militant groups. Add to the mix concerns over immigration, economic integration and issues of national identity, and anxieties appear ready to boil over. That is particularly evident in Germany, where the rapid rise of the anti-immigrant, anti-Islamic group Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamization of the West has alarmed leaders.

Since its formation last October, this movement, known as Pegida, has channelled frustration over the government’s inattention to the needs and problems of average citizens into resentment over the influx of immigrants and refugees into Germany. After the terror attacks in Paris, record crowds swelled in Dresden with chants of “We are the people.” The movement has gained tens of thousands of adherents—even a Catholic priest, the Rev. Paul Spätling, was heard at a rally in Duisburg, purportedly spreading anti-Islamic stereotypes.

In response, Bishop Felix Genn of Münster promptly stripped the priest of his preaching faculties, saying that Father Spätling’s xenophobic comments had no place in the church. The archbishops of Cologne and Aachen have called on Europeans to take seriously the suffering of refugees who arrive from crisis regions. Chancellor Angela Merkel has urged Germans not to follow those whose “hearts are cold and often full of prejudice.” These admonitions need to be heeded as Germany confronts its own economic and political crises.