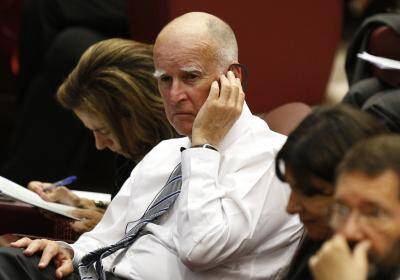

California is now the fifth and largest state in the country to allow doctors to prescribe life-ending medication to patients. With the signing of the End-of-Life Option Act by Gov. Jerry Brown on Oct. 5, the so-called right to die movement scored a major victory. Several other states, including New York, are considering similar bills that will surely be boosted by the momentum initiated in Sacramento.

In attempting to allow individuals to “die with dignity,” these laws end up devaluing life at all stages and elevate an idea of freedom that is fundamentally at odds with an authentically human understanding of individual dignity in relation with God and community. But there are many other persuasive arguments against assisted suicide laws that deserve a wide hearing. One need not be a Christian or a believer to see the serious problems with laws that legalize a “right to die.”

In a letter released on the day the California law was signed, Governor Brown explained his reasons for supporting it. “I do not know what I would do if I were dying in prolonged and excruciating pain,” the governor wrote. “I am certain, however, that it would be a comfort to be able to consider the options afforded by this bill. And I wouldn’t deny that right to others.”

The governor’s argument was heartfelt and, from a limited viewpoint, compelling. Many people who support “right to die” legislation are motivated by a strong sense of compassion for those who suffer. Yet the scenario presented by Governot Brown presents only part of the picture. People who suffer near the end of their lives do not make these critical decisions in a vacuum. Their suffering includes not only physical pain but sometimes also despair over the absence of people to depend on or resources they need. This law does nothing to address that lack of support; indeed it suggests that the right response is not to ask for help in bearing suffering but rather for assistance in removing the perceived burden their lives have become.

California’s new law was passed against the strong resistance of the disability rights community. These advocates have argued time and again that the introduction of assisted suicide laws into a for-profit health care system is a dangerous experiment. The plain fact is that it is less expensive to administer life-ending drugs than to pay for pain management or extended hospice care. It should give us pause that California’s End-of-Life Option Act was passed while the legislature was considering ways to address funding shortfalls for Medi-Cal, the state’s health insurance program for the poor. In that effort, they were unsuccessful. As the state’s Catholic bishops pointed out, California’s poorest residents do not have access to palliative care, yet now they have the right to end their lives.

It is naïve to believe that people in California will not feel pressure to end their lives as a result of the new law. To pretend otherwise is a failure of empathy. We are able to respond to the suffering of Brittany Maynard, a vibrant young woman who received a wave of social media support for her decision to end her life in the face of terminal cancer. Yet we do not often think about what it will be like for an elderly woman who cannot pay her medical bills in a society that preaches the “right to die.”

The law’s advocates argue that the scope of the legislation is limited. Physicians are allowed to prescribe life-ending drugs only to individuals who are deemed mentally competent and are expected to die within six months. Two doctors must sign off on the order. But medical prognoses are sometimes wrong. And the reasons most frequently cited for seeking life-ending medication have more to do with loneliness and fear than disease. In Oregon, a state in which assisted suicide has been legal since 1997, “loss of autonomy” and “loss of dignity” are two of the most common reasons given for wanting to end life. The fact that all we are willing to offer individuals in these circumstances is an opportunity to die is an indictment of both our health care system and the community in which it is embedded.

In 2008 Barbara Wagner and Randy Stroup, both suffering from cancer, sought payment for their treatments from the Oregon State Medicaid system. Their requests were denied, but among other options listed, the state offered to pay for life-ending drugs. (The offer was later rescinded when the letter was made public.) Their cases are a reminder that introducing the “right to die” into our health care system—especially in a large state like California, with its complex bureaucracy—will have many unintended consequences. Passing such legislation does not make us more “compassionate.” Instead, it reveals our failure to adopt the perspective of those who are truly most in need of our compassion.