By the time Nov. 13 came around, I was well adjusted to the 10-and-a-half hour time difference between New York City, my hometown, and Bengaluru, one of the largest cities in South India, where I was pursuing a study-abroad program on international development. In addition to the time difference, the spotty internet connectivity and frequent power outages hampered my ability to communicate with my family and friends, let alone keep up with the 24-hour news cycle.

But on that morning, the only message I needed to hear appeared quite clearly to me, even as the broadcasters chattered in Kannada, the local language, and struggled to make sense of the still-emerging details about yet another massive terrorist attack, this time in Paris. As I frantically searched for the BBC on the channel guide, I became filled with the familiar feelings of sadness, anger and stress that always color these scenes. In this moment, I thought of and longed for home, 8,300 miles away, where I had first experienced this combination of emotions 14 years earlier, as my first grade class was interrupted by the news that a plane had crashed into the World Trade Center, just miles away from my elementary school.

As a member of the generation brought up in the dark aftermath of the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, I can point to several ways in which the social environment of my childhood played a central role in the formation of my current worldview. As the son of a first responder, for instance, I will forever have the deepest gratitude for the heroes in uniform who risk and sometimes sacrifice their lives to keep my community safe. At the same time, the strength and love my local community demonstrated during those dark weeks and months persists as we collectively face new challenges. But when I consider the influence of this environment on my Catholic faith, it is exceptionally difficult to develop similarly clear conclusions.

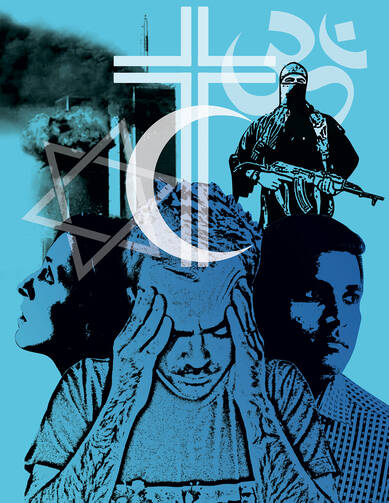

Raised in an era marked by terror fueled by religious extremism and intolerance, I struggle. I struggle with the knowledge that the cover of the newspaper often shakes my belief in the basic goodness of people, as I confront images of a bombed train or bullet-ridden restaurant. I struggle as blood continues to be shed around the world, frequently that of the most marginalized. Most of all, I struggle as I hear talk about how terrorism demonstrates that people of different faiths cannot coexist, and that conflict and destruction are inevitable.

But in the face of powerful voices that so often tell my generation that pursuing peace is an admirable but naïve goal, I have hope. In the past few years, I have been blessed with numerous opportunities to see people around the world, in ways large and small, counter this narrative about the end of civilization. In my struggle to make sense of my faith in a chaotic, often violent world, I have looked outward, discovering moments that reaffirm our common humanity. This ongoing personal journey has proved enormously rewarding; indeed, as I learn how multifaith cooperation manifests itself on the ground, my faith in God and the saving message of the church have been reaffirmed and strengthened.

The University of Richmond has generously provided me with numerous chances to explore simultaneously my passions for travel and learning. Two years ago, I traveled with a group of students from the office of the chaplaincy to Poland, where we explored questions of memory and reconciliation in the context of the history of the Holocaust. The pilgrimage was emotionally powerful, and I will carry many of the harrowing images from my time there with me for the rest of my life.

Today, I vividly recall encountering people and organizations devoted to the preservation of memory and to educating a new generation about one of the darkest chapters in human history, with a firm understanding that honest dialogue can begin only after we, as a society, make a good-faith effort to understand the experiences of others—in this case, relating to the way the grim legacy of the Holocaust partly shapes modern Jewish identity. This experience made clear to me that memory is a key part of keeping faith in the modern world, both to preserve sacred traditions and understand the perspectives of others in order to advance a more inclusive view of what a modern society ought to look like.

Just one year later, I found myself aboard a plane bound for Ben Gurion airport in Tel Aviv on another pilgrimage. Having decided to solidify my interest in the study of another religion by declaring a minor in Jewish studies after the Poland trip, I was exhilarated as I set foot in Israel with other Catholic, Protestant, Jewish and Muslim students. We were there to study the shared origins of the Abrahamic religions and to make connections with the contemporary efforts to ensure peace in the Middle East.

During this visit, I soaked in the many breathtaking sites that the land has to offer. I found myself most captivated by conversations with local people, who passionately shared their narratives about claims of ownership in the region and frequently expressed their desire to live in peace with their neighbors. I walked away from this with a much more nuanced view of the complexities of multifaith coexistence but also, critically, an understanding that although some people, like the terrorists who attacked New York 14 years ago, may pursue death and destruction, there are a great many in all faith communities with a firm desire to pursue life, even if just on their own streets.

I capped off 2015 with a four-month study-abroad program in Bengaluru, India. One anecdote well captures for me the beauty of my time there. Traveling around the city was stressful because of the language barrier, lack of transport options and faltering infrastructure. There were no churches within walking distance of my home, but I wanted to attend Mass.

During my first week, I anxiously prepared for the half-hour trip to the church. My discomfort must have been obvious to my Hindu host family. They generously agreed to ride with me to the church, but I was very surprised when they then decided to attend Mass with me. I could tell that they did not understand much of what was taking place, but as we linked hands for the Lord’s Prayer, I found myself at ease for the first time since arriving in this foreign land.

When news of the attacks in Paris arrived weeks later, I thought not only about home, but also about that personal experience of cross-faith unity. I understood that even in the face of sometimes vicious divisions and religious violence, I could rest firmly in my Christian belief that another day would come and that the instances of mutual understanding I had witnessed in the previous year were not anomalies but rather glimpses into a better future, however far away that might be.