‘I guess we never see the plan,” Kay said to me with resignation. I sensed no resentment in her voice; on the contrary, I heard undertones of confidence. She was sitting across from me at the breakfast table after Mass. I had just preached on our being God’s “handiwork” (Eph 2:10) and had suggested the image of God as a sculptor working in our lives like Donatello, Michelangelo or Bernini, chipping away at a block of marble with a plan in mind that only he can see, wielding hammer and chisel, and then sanding, polishing and refining until the final product was a thing of beauty.

Kay was alone in life. Her two sons died when they were in their 20s. Her daughter passed on soon afterward, succumbing to cancer prematurely. A few years later, her husband went into the hospital for a routine operation on his knee and died when a blood clot hit his heart. Although she rarely spoke about what she believed, I sensed that she had a quiet, enduring hope in the hidden plan of God. As I listened to her across the table, I thought of Emily Dickinson’s words:

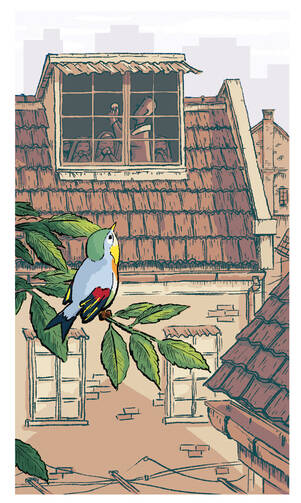

Hope is the thing with feathers

That perches in the soul,

And sings the tune—without the words—

And never stops at all.

So many of life’s events conspire to beat hope down. But perched in the soul of the stalwart, it chants its tune persistently. Sometimes it expresses itself in the simplest ways. Over the years several incidents have made me ponder the resiliency of hope.

The first occurred almost two decades ago in China. One evening I received precise instructions: At 4 a.m. I was to leave the hotel where I was staying. Once outside I was to turn right and follow, at a distance of 50 feet, a woman who would guide me through dark streets to the Mass I was to celebrate. I followed her for about 15 minutes. Then, suddenly, I saw a door open, and my guide slipped inside quickly. When I arrived at the same spot, the door opened, again and I entered. We climbed four flights of stairs silently and then knocked gently on a door. After a pause, someone opened the door and we went into a tiny attic. There, hidden away in mainland China, I celebrated Mass with 14 elderly members of the Daughters of Charity. When someone tapped on the door just after Mass began, everyone froze with tension for fear that the police were arriving, but it was another sister.

These Chinese nuns have been cut off from their community for 45 years. That day they renewed their vows in this candle-lit attic with great emotion; this was the first time they were gathered together like this since 1949. They had remained faithful, in hiding, all those years. They were very poor. They prayed daily in private and went out almost every day to serve the needy. One told me that in 1950 she had been questioned for seven days and seven nights without rest, her interrogators taking turns, and was then thrown in prison for 30 years.

During my journey, I found 70 elderly Daughters of Charity in mainland China. They had been living underground, in hope, for decades. Though I offered them financial help, they refused. They told me that they had all they needed and radiated confidence in the transforming power of the Gospel.

The second incident occurred much closer to home. About eight years ago, my niece lost her 2-year-old baby, Maeve. Hundreds of people came to the wake. After Maeve’s coffin was closed, someone overheard her brothers and sisters talking. Her littlest brother said, “Is she playing inside that box?” His older sister replied, “No; Mama says she’s playing in heaven.”

Maeve never learned to walk, nor did she ever speak. The handicap with which she was born impeded her growth from the start and then abruptly stole her life away. But she lived and died evoking love and radiating it back. Her father said at her funeral, “Every time you saw her, you wanted to kiss her.”

When we witness death, we often ask why; all the more so with a child. Why was Maeve born with disabilities? Why did she die long before those who loved her and nourished her? Sometimes in anger we blame God and ask, How can a good God let a child like Maeve die? Questions like this are perennial. Thomas Gray lamented:

Full many a gem of purest ray serene

The dark unfathomed caves of ocean bear.

Full many a flower is born to blush unseen,

And waste its sweetness on the desert air.

We have no ready answers to such complaints, only a persistent hope that points us beyond our grief. A feathered thing perches in our souls, singing out.

Hope moves us to ask not just why Maeve died, but why she was born in the first place. Had she not been born, would her mother and father and brothers and sisters have ever loved as they learned to love during the two years of Maeve’s life? Would they ever have learned to give as they gave and to pray as they prayed? If heaven is union with those whom we love, then was Maeve’s presence in her family its foretaste? Maeve reminded us that the communion of saints is a communion of human imperfection; one of its building blocks is what we make of our own weakness and the weakness of those who surround us. A grieving woman, who had just lost a child, once wrote: “Some may wonder why, after my experience, I still make the painful effort to believe. I can only respond that, despite my doubts, having seen the breathtaking perfection of my daughter’s peaceful face, I find it impossible to believe that God was not there.”

The third incident occurred recently. I was giving a talk about an AIDS project that I work with in Africa. In my introduction, I told the audience that 22.9 million people in sub-Saharan Africa were living with AIDS and that only a small fraction of them would receive the type of treatment that is now available in the United States and Western Europe. So, millions would die, even though, with well-monitored drug therapy, they could have lived a normal life span. After my talk a priest in the audience came up to me, shaking his head, and said, “It’s hopeless.”

But that evening I found myself reflecting on the thousands of people who are dedicating their lives to AIDS care in Africa. The feathered thing perched in their souls resists the temptation to quit. It sings a song that cannot be silenced. I thought of the lovely image of hope attributed to Augustine: “Hope has two beautiful daughters. Their names are Anger and Courage: anger at the way things are, and courage to work to change them.” Anger, Hope’s first daughter, reacts spontaneously in the face of evil, refusing to accept unjust social and economic structures that deprive the poor of life: unjust laws, power-based economic relationships, inequitable treaties, artificial boundaries, oppressive or corrupt governments and numerous other subtle obstacles to harmonious societal relationships. Then Hope’s second daughter, Courage, standing at Anger’s side and singing out persistently, searches for ways “to strive, to seek, to find and not to yield,” as Tennyson put it.

One of the world’s most persistent nighttime singers is the nightingale, a small, plain brown bird with a reddish tail. It chants on and on with remarkable beauty and endurance. Keats immortalized the hope it proclaims:

Thou wast not born for death, immortal Bird!

No hungry generations tread thee down;

The voice I hear this passing night was heard

In ancient days by emperor and clown.

These days Latin American theologians speak of la esperanza transformadora, “transforming hope.” Without it life is pessimistic; little movement toward change takes place. But when transforming hope resides in a person, it generates the energy we call anger and initiates creative action. Perched in the soul, it sings its song persistently. It cannot be dissuaded.

Christian hope is both realistic and optimistic. It is realistic because it recognizes life’s tragedies: sickness, sin, infidelity, suffering, natural calamities, violence, war, death. But it is optimistic because it trusts in a new heaven and a new earth, where sin and death are vanquished. Believing in the words of the Creed, on which we rarely reflect, it looks forward to “the resurrection of the body” and “the life of the world to come.”

In the midst of one of the Czech Republic’s most difficult times, Václav Havel stated: “Either we have hope within us or we don’t. It is a dimension of the soul…. Hope in this deep and powerful sense is the ability to work for something because it is good, not just because it stands a chance to succeed…. It is this hope, above all, that gives us the strength to live and continually to try new things, even in conditions that seem as hopeless as ours do here and now.” That kind of hope is the feathered thing that perches in the soul—and enables our hearts to soar.