I know a Jesuit whose father worked at the same company for 56 years. A friend and mentor just retired after 35 years at the same company, and my father has only recently begun to decelerate after practicing orthopedic surgery for almost 40 years.

I am 33. After graduating from college at 22, in St. Louis, Mo., I taught at a high school in Phoenix, Ariz., attended law school in South Bend, Ind., practiced law back in Phoenix and returned to teaching high school—in Palm Desert, Calif. My travels have spanned three Jesuit institutions, two law firms, one federal prosecutor’s office and four states.

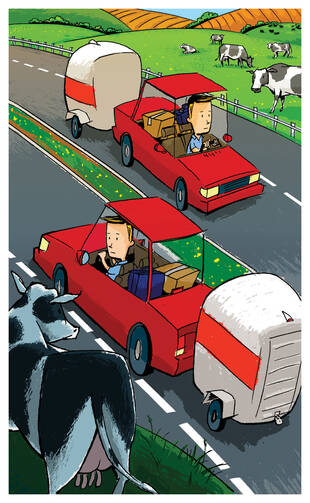

During the past decade, I spent hundreds of hours on U.S. interstates gazing into deserts and farmland, hoping for my own burning bush. I saw mostly cows. And as I made my way through this cattle-encountering, debt-amassing quest, I started to wonder: Was I afraid to commit? Would my career search last a lifetime? Was I part of a generation too privileged to appreciate a good job?

And more than anything: Why was it so hard? Why couldn’t I just figure it out?

Four years ago, as I approached 30, I finally settled into a role that gave me the fulfillment and the focus I had been seeking. I now divide my time between writing, teaching and speaking, a synthesis of responsibilities that enables me to feed many interests, make a living and, most important, feel confident that I am following God. Now, when I look back on my 20s, I’m not embarrassed that I bounced around, but grateful.

With a few years to reflect, I know my moving around was not aimless. My restlessness grew from something good, from spiritual hunger. I wanted to commit to a career that reflected what God wanted of me. Ambition or ego occasionally obscured that desire, but it always resurfaced—on a late-night drive back from the office; during the silence of a Saturday morning; in the calm before Mass. In other words, my roaming derived from an authentic, inquisitive spirit. I was restless for the right reasons.

My 20s demonstrated that success is a mixed blessing. Achievement is not contentment. What to friends and family should be uncomplicated reasons for happiness can possess the character of crystal: alluring but brittle. Not long after graduating from law school, I worked as an associate at a large law firm. The job earned me respect and good money, and I was mentored by talented, caring colleagues. But as I imagined making partner, as I imagined buying a house, investing, marrying—completing the milestones that, in our culture, constitute “settling down”—I grew restive and melancholy. I began to ask the question the rich young man directs to Jesus: “What do I still lack?”

As I tried to reconcile inner tensions, I realized I would have to submit to a period of instability and uncertainty, a prolonged period of not knowing. For that I was unprepared. For years I had a plan; I could always see the next rung. As an adult, the path was supposed to be similarly clear: choose a career, begin a family and head for retirement.

But in my mid-20s, in the midst of a spiritual crisis, I realized that pursuing these goals on the typical timeline leaves little room for the trial and error, the flexibility and freedom that discipleship requires. Growth in the spiritual life, I discovered, cannot be scheduled. I could have settled as a teacher at 23 or a lawyer at 27, but I would have missed out on experiences and encounters that became essential in my search for God.

I met lawyers whose vestments of prestige hid long-festering despair. I sat with the poor at legal aid clinics, finding they needed legal advice far less than they needed to be looked in the eye. I have watched students wrestle with God’s existence and then speak of a hope for faith. I have counseled students on everything from Christ to college essays to the rules of evidence. Most joyfully, most wonderfully, my searching over the past 10 years led me to the woman with whom I will spend my life, to my fiancée. (We met—how’s this for God’s wink?—at a fundraiser called the “Jesuit Companions’ Dinner.”)

Finally, I learned that in the effort to live as a disciple, it is not so much about finding a particular career, a particular place or a particular combination of roles, as it is about finding a particular attitude that endures no matter where we are or what we do. It is an attitude of trust, a willingness to let God refashion our preferences in the refinery of God’s will. It is the desire to offer our lives, not as a demand to be met, but as a constantly unfolding eighth day of creation.

Let there be light.

Correction: The author is 33, not 32.