The Pentagon’s invitation to travel to Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, to report on military commission hearings captured my interest and imagination, but there was one problem: I had my own court date to deal with. I recently had been arrested at the Pentagon and was scheduled to appear before a judge in U.S. District Court the same week as the Guantánamo hearings. On the anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Japan, I knelt in prayer with five others outside the Pentagon in sackcloth and ashes, praying for our government to abolish nuclear weapons. Moments later, we were handcuffed.

The case prosecutor, when I called him, said not to worry about requesting a delay for the hearing; he planned to drop the charges altogether. Then, like a concerned parent, he admonished me for stepping outside of the designated “free-speech zone” and failing to obey police orders. It was a merciful reprieve—an experience of “American justice” unrecognizable to Guantánamo detainees, some of whom, unlike me, had violated no law at all. Just two days after the prosecutor’s de facto pardon, I boarded the plane for Guantánamo.

The purpose of the trip to Guantánamo Bay was not only to report on courtroom proceedings but to have a closer, more personal encounter with the people, place and legal system in which I am invested and for which I feel responsibility. For years I have studied U.S. detention policies at Guantánamo, become familiar with prisoners’ names and stories, tried to speak out against prisoner abuse and torture and advocated for human rights and the closure of the prison. In 2010 four Uighur men, detained in Guantánamo for seven years, described their experience to me.

During the flight to Guantánamo, I felt a mix of fear and excitement, having no idea what to expect. Whom would I meet? What would I see and have access to? Would it make me angry, depressed or hopeful that the prison will eventually close? I also worried about whether I could abide by all 10 pages of media rules. What if I made an innocent mistake or my conscience dictated otherwise?

As we approached the island, a small naval ship passed through the deep blue Caribbean waters and misty air below. Rocky cliffs, rugged green terrain and winding dirt roads came into view. A lone mountain set the background. The runway paralleled the coastline. As the plane touched down, the flight captain welcomed us: “Have a good time here in Cuba.”

Seriously? I thought. Have a good time? It was hard to fathom how this experience could possibly be a “good time,” or why anyone would even have this expectation. For 779 detainees, landing on the naval base—mostly during the prison’s first two years—was not nearly as idyllic or fortunate. They weren’t able to enjoy the beauty of the land or sea because, in transfer, they were subjected to sensory deprivation, a form of torture. Detainees arrived in Guantánamo wearing ear muffs and blacked-out goggles, leaving them dazed and confused.

Even worse: A flight to Guantánamo, in hindsight, was the final flight for nine detainees who later died in confinement. The most recent victim was Adnan Latif, who reportedly died from an overdose of psychiatric medication in September. (Questions remain as to what precipitated this.) Meanwhile, many of the remaining 166 prisoners face the prospect, at the current rate of transfers, of growing old and dying in Guantánamo. When they first landed here, did they ever imagine this possibility? While some of the prisoners claim membership in Al Qaeda, most do not; and most will never be charged in any military or civilian court.

As it turned out, members of the media were not allowed to see much of the naval base or visit the prison camps. Instead we spent most of our time in a tightly restricted place named Camp Justice, of all things—home to residential tents, the media center, a recently constructed $12 million maximum-security legal complex and plenty of bright orange barriers and chain-link, razor-wire fences to boot.

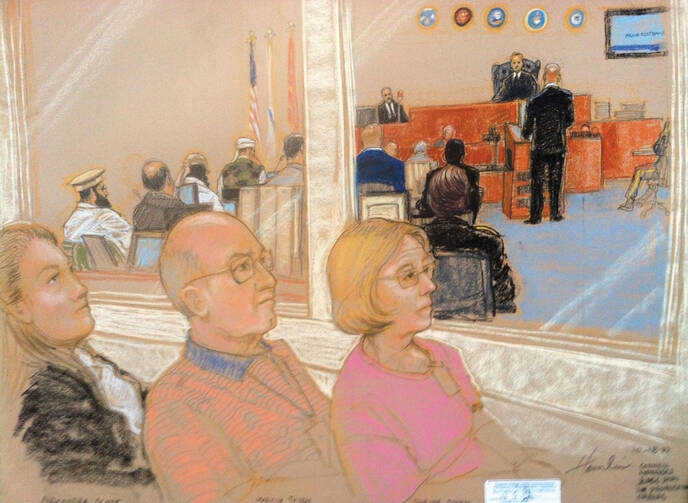

In the viewing area adjacent to the courtroom, we sat behind thick, soundproof glass. My eyes darted between the silent scenes, unfolding live, and monitors broadcasting the sights and sounds of the proceedings with a 40-second delay. A conflicted chief prosecutor, Brig. Gen. Mark Martins, defended a system of justice that military personnel, he told The New York Times, “aren’t enamored of,” adding that he still believes “there is a narrow category of cases in which reformed military commissions are the best choice to achieve justice.” Military officers passionately defended the dignity and human rights of their clients—an unpopular cause, considering that the five defendants stand trial for helping plan the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, that killed nearly 3,000 Americans. And I also saw military police and defendants simply being kind to one another, at least in the courtroom.

But nothing touched me more deeply than talking with a group of family members who lost loved ones on Sept. 11. Before this trip, I focused mainly on detention policies and human rights, and I still firmly believe that each prisoner should be tried in federal court or immediately released; the prison in Guantánamo and its counterpart in Afghanistan need to close. But that is only the beginning.

In Guantánamo, my vision of justice expanded. There is a need for healing and reconciliation that goes beyond the courtroom. Legal rights and humane treatment are important, but so is the pain and frustration experienced by family members who have waited more than a decade for this trial to commence.

Gordon Haberman, who lost his daughter Andrea in the World Trade Center on Sept. 11, expressed his desire to visit the prison camps and personally confront Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, who has claimed responsibility for plotting no less than 30 acts of violence internationally, including the Sept. 11 attacks. Mr. Haberman’s request to talk with Mr. Mohammed, however, was turned down. But why?

Our system of justice needs to move beyond the functional tasks of simply identifying the crime, the culprit and the punishment. A framework of restorative justice, promoted by many faith-based groups and human rights organizations, poses a different set of concerns: Who has been harmed, what kind of healing needs to take place, and how can every person participate in reconciliation? This creates a space not only for lawyers and judges, but for victims and their loved ones.

There have been, no doubt, countless victims related to Guantánamo: the rule of law itself; those who died on Sept. 11; Muslim men, including Mr. Mohammed, tortured by the United States; soldiers and civilians killed or injured in the Afghanistan and Iraq wars; and even those who carry out acts of terrorism, war and torture—blind to the human cost of such violence.

Guantánamo afforded me the privilege of being in conversation with a few soldiers and family members, and being in close proximity to the prisoners. Now, back home, I better understand the need to create space to share our experiences, listen to one another, repent of wrongdoing and make amends. Together we can forge a path to healing and reconciliation.