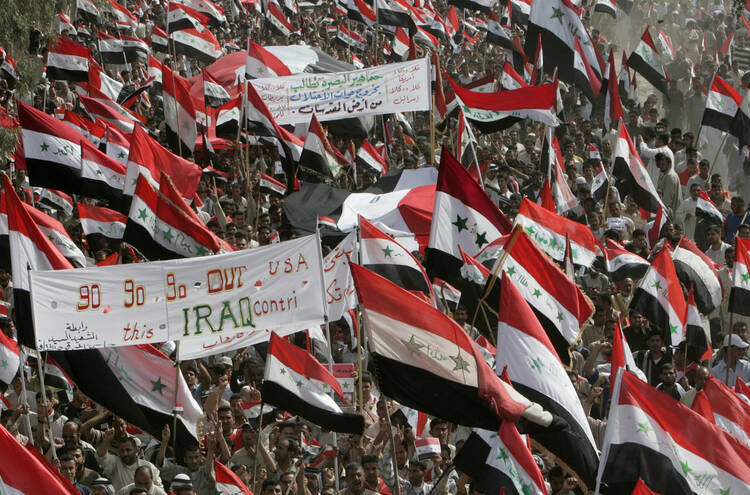

In March 2013, I visited Iraq to attend the installation of Monsignor Louis Sako as the new Chaldean Catholic Patriarch. During that visit, I had a brief, yet startling, introduction to the country in the aftermath of dictatorship, invasion, occupation and civil war. The comments of my Iraqi interlocutors are engraved in my memory. Many insisted "the Americans ruined Iraq" and "the Americans ruined the church."

The tragedy of Iraq today could have been predicted given U.S. policy decisions in 2003. Many warned that the invasion would lead not only to the death and destruction inevitable in war, but to wider economic, political and social tragedies for Iraq, the United States and the global community. The Holy See and U.S. bishops were prominent among those voices, basing their concerns on the church's moral teaching on war, peace and international relations.

This review of the church's engagement with U.S. policy in Iraq is meant to help ensure that the moral obligations and limits on our nation’s conduct in the world will not again be ignored. In the future, we must ensure that our foreign policy is morally sound, cognizant of the consequences of U.S. action and thus better able to advance security, stability and a just peace.

Before March 2003, certainly, Iraq was a country in crisis. Its government was a threat to its own people and its neighbors. While decrying the harmful impact of U.N. economic sanctions on innocent Iraqis, the bishops wrote in November 1998: "The Iraqi government has a duty to stop its internal repression, to end its threats to peace, to abandon its efforts to develop weapons of mass destruction, and to respect the legitimate role of the United Nations in ensuring that it does so."

The Morality of Going to War

The first grave U.S. failure was to ignore how complex, demanding and enduring its responsibility to Iraq would be after the overthrow of Saddam Hussein, and to plan accordingly. Despite warnings, senior U.S. leaders failed to meet their moral obligation to plan for, as far as possible, a successful occupation. The church was prominent among cautionary voices. In September 2002, Archbishop Wilton Gregory, then president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, wrote President George W. Bush:

The use of force must have "serious prospects for success" and "must not produce evils and disorders greater than the evil to be eliminated" (Catechism of the Catholic Church, no. 2309). War against Iraq could have unpredictable consequences not only for Iraq but for peace and stability elsewhere in the Middle East. Would preventive or preemptive force succeed in thwarting serious threats or, instead, provoke the very kind of attacks that it is intended to prevent? How would another war in Iraq impact the civilian population, in the short- and long-term? How many more innocent people would suffer and die, or be left without homes, without basic necessities, without work? Would the United States and the international community commit to the arduous, long-term task of ensuring a just peace or would a post-Saddam Iraq continue to be plagued by civil conflict and repression, and continue to serve as a destabilizing force in the region?

Beyond deposing Saddam Hussein, the United States government seemed to give little thought to real and lasting success in Iraq. On the eve of invasion, in February 2003, Archbishop Gregory reiterated the concerns of the bishops and made explicit the requirements for a morally valid policy: "A post-war Iraq would require a long-term commitment to reconstruction, humanitarian and refugee assistance, and establishment of a stable, democratic government at a time when the U.S. federal budget is overwhelmed by increased defense spending and the costs of war."

Beyond probability of success, there were failures related to other principles of the just war tradition:

- Right Intention/Last Resort: While there was legitimate concern about the threat Saddam Hussein posed, the admitted absence of a specific and imminent threat and ability to use weapons of mass destruction (WMD) against our nation or others raised questions about the urgent pursuit of war. Invasion was clearly not a situation of "last resort."

- Just Cause: Our government posited a long-term self-defense rationale, resting on the proposition that WMD in Iraq would pose a threat to core U.S. interests and that, even if the threat was not imminent, the nature of WMD was such that a new standard—preventive war—was justified. The church has rejected this innovation to the just war tradition. As Archbishop Gregory stated clearly in February 2003: "To permit preemptive or preventive uses of military force to overthrow threatening or hostile regimes would create deeply troubling moral and legal precedents."

- Right Authority: All states may use force unilaterally in self-defense. Absent attack (or a pre-emptive strike in response to imminent attack), the obligations of Chapter I, Article 2 of the U.N. Charter apply, and argue strongly for the application of the terms and procedures of Chapter VII of the Charter. Archbishop Gregory stated in a September 2002 letter to the President: "… in our judgment, decisions of such gravity require … some form of international sanction, preferably by the UN Security Council."

- Proportionality: Proportionality requires that "the use of arms must not produce evils graver than the evil to be eliminated (Catechism, no. 2309)." This includes not only death, injury and material damage, but also the social, political and moral damage war inevitably causes. The various statements and letters of the U.S. bishops repeatedly raised questions of proportionality.

Weighing all these considerations, Archbishop Gregory’s September 2002 letter ended:

We conclude, based on the facts that are known to us, that a pre-emptive, unilateral use of force is difficult to justify at this time. We fear that resort to force, under these circumstances, would not meet the strict conditions in Catholic teaching for over-riding the strong presumption against the use of military force. Of particular concern are the traditional just war criteria of just cause, right authority, probability of success, proportionality and non-combatant immunity.

“Regime change” was too facile a goal and did not take account the unintended consequences and grave moral responsibilities of invasion and occupation.

The Morality of Occupation

In the wake of the U.S.-led invasion, as the depth of Iraq's needs became undeniable, leaders in the United States committed another moral error by failing to respond responsibly. The rejection of a direct U.S. police role, the disbanding of Iraqi military and police and the indiscriminate dismissal of Ba'ath party members from the Iraqi administration left a vacuum of governance, permitted lawlessness to spiral out of control, undermined Iraqi trust and confidence in the United States and its coalition partners and alienated many of the country’s Sunnis.

In January 2006, Archbishop Thomas Wenski, then Chairman of the Committee on International Justice and Peace, issued "Toward a Responsible Transition in Iraq," a statement setting forth the moral framework and many specific requirements for the occupation:

The intervention in Iraq has brought with it a new set of moral responsibilities to help Iraqis secure and rebuild their country and to address the consequences of the war for the region and the world. The central moral question is not just the timing of the U.S. withdrawal, but rather the nature and extent of U.S. and international engagement that allows for a responsible transition to security and stability for the Iraqi people.

The benchmarks for a responsible transition were based on longstanding church teaching on what was necessary for true peace and justice. Peace is more than the absence of war. As the Catechism teaches: "Finally, the common good requires peace, that is, the stability and security of a just order. It presupposes that authority should ensure by morally acceptable means the security of society and its members” (no. 1099).

On behalf of the bishops’ conference, Archbishop Wenski and later Bishop William Skylstad, then president of the U.S.C.C.B., spelled out the elements of a “responsible transition.” These included:

- Achieving Adequate Levels of Security: From the massive looting following the occupation of Baghdad until the 2007 "surge," U.S. forces at first did not intervene to secure order and thus never re-established basic security. The consequences were soon apparent. Civilian deaths rose from roughly 610 per month in the first six months after May 2003 (the end of major combat operations) to over 1,200 per month by mid-2005 and exceeding 3,000 per month prior to the surge (Iraq Body Count). Material damage rose in tandem. Critically, the violence and lack of effective occupation and governmental response led Iraqis to fall back on older sources of security—sectarian and/or tribal militias. Security remains elusive today, except in the Kurdish region where its more homogenous ethnic makeup and access to resources has allowed a different trajectory of recovery.

- Establishing the Rule of Law: Justice, a founding principle and primary social good in Islam as in Christianity, should have been a core policy goal. Securing justice required dealing justly with wartime wrongdoers, establishing a functioning police and judicial system and establishing a more just society for all. The first of these was accomplished, albeit imperfectly, by Iraqi authorities seeking to apportion responsibility individually and punish the guilty accordingly. But other justice-related goals were only partially met, in large part because of the absence of the security and social trust needed to build necessary institutions.

- Promoting Economic Reconstruction: The United States and other nations contributed enormous sums and technical resources to economic reconstruction. Aid funds were increasingly supplemented by Iraqi funds from oil exports. Considerable progress in the delivery of basic services was made, but a lack of skills, corruption and, above all, continued violence undermined these efforts. Iraq's economy remains plagued by high unemployment, lack of investment, corruption and the effects of crony capitalism and political interference.

- Supporting the Development of Just and Democratic Political Structures: Overcoming multiple social divisions and creating a civic culture and political system that advances the common good was, and remains, the most intractable problem confronting Iraq. Although the U.S. and other donors made great efforts to achieve this goal, the lack of security exacerbated social and political tensions. Unless the occupation forces and transitional government could enjoy something close to a monopoly of force and ensure individual security, it was doubtful that meaningful social reconciliation, economic reconstruction or political development could be realized.

The Moral Impact on the United States

The bishops warned that an attack on Iraq would have grave human, material and moral consequences for the United States as well as Iraq. In April 2007, they wrote to Congress: "U.S. policy must take into account the growing costs and consequences of continued occupation on military personnel, their families, and our nation. There is a moral obligation to deal with the human, medical, mental health, and social costs of military action." They also questioned the diversion of resources from pressing domestic needs, the impact on America's international standing and influence and a possible increase in global terrorism. Some 4,500 Americans died in Iraq; thousands more were injured. The material and financial costs of the war have diverted resources from other national priorities, to the detriment of the most vulnerable in American society. A 2013 study sponsored by Brown University has put the cost of U.S. intervention in Iraq at $2.1 trillion, with future costs (e.g., care for veterans) of perhaps another $4 trillion.

After 9/11, our nation was united in the conviction that combating terrorism required vigorous, new security measures. The Iraq war fractured this consensus and deepened and hardened fault lines in American society. The Iraq war may also have contributed to attitudes that stigmatize or burden our fellow Muslim citizens as a group and Islam as a religion. The war in Iraq has undercut America's ability to act as a force for the universal common good of the world, likely spurred terrorism, provoked greater opposition to the United States in the Islamic world and made cooperation with regional partners more difficult and dangerous.

The church teaches "the damage caused by an armed conflict is not only material but also moral" (Compendium, no. 497). Human rights concerns figured prominently in the bishops' letters and statements on Iraq: "Amidst the difficulties of building a stable, democratic Iraq, the special importance of basic human rights, especially religious freedom, should not be neglected. The inherent dignity and equal worth of all Iraqis must be respected" (“Statement on Iraq,” 2004). The moral tragedy of the invasion of Iraq is epitomized by human rights abuses at Abu Ghraib prison in 2003-05, and by official attempts to justify torture as a counter-terrorism tool. U.S. forces and occupation authorities generally sought to act in keeping with human rights norms and have prosecuted many offenders. Nonetheless, American society has to some degree been morally coarsened by human rights abuses in Iraq.

Lessons Learned

The Iraq war taught lessons we Americans must not forget. First, to ensure that the outcome of a war is "a more perfect peace," providing security is the first and essential goal. Without security, individuals and groups will seek security in extra-legal or illegal ways. In a fractured society, like Iraq's, this can quickly lead to a war of tribe against tribe. Absent security, achieving the many other goods intrinsic to a just post-war settlement is at best improbable and perhaps impossible.

Second, the use of armed force to resolve conflicts with and within broken societies is likely to fail. A just peace is not simply a matter of regime change, but must also involve the provision of security and the (re)establishment of an at least minimally just national life. Difficulties and dangers lie in the scale and scope of these tasks, and in securing the resources and maintaining the political commitment and support needed over many years to achieve them. Much more attention than was the case in Iraq must be paid by leaders to these moral responsibilities before military action is begun.

Third, the moral teaching of the church on war and peace, which also is the foundation for international law, provides a compelling and coherent guide for government action in situations of conflict. We ignore it at our peril. We risk unintended consequences. As we Americans contemplate our future engagement in global affairs, we must keep these lessons close, strongly constraining the urge to use force to right wrongs by instead robustly adhering to the moral principles of a just use of force and of the establishment of a just peace.