By noon the parade was over, and the revelers had gathered in a park on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. They shared cigars, gave speeches and drank from kegs of lager “mounted in every conceivable place.” The occasion was the first Labor Day parade, held on Sept. 5, 1882, and though police feared riots, the day passed without incident. The lively crowd of union workers and supporters represented a burgeoning force in American public life.

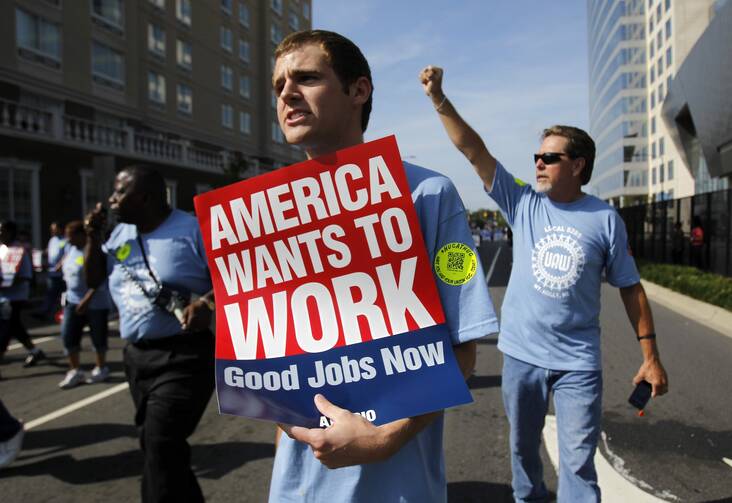

This year, Labor Day festivities are likely to be more muted. Given its well-reported setbacks, the labor movement can seem hardly worth celebrating. In addition to a steady decrease in union membership, labor leaders face formidable opponents in Congress and statehouses across the country. In June the Supreme Court ruled that home health workers employed by the state did not have to pay union dues, a decision some worry will lead to nationalizing state-level “right to work” laws. Meanwhile, many people are having difficulty finding full-time work as more employers use part-time workers to reduce costs.

Still, the labor movement is far from moribund, and the past year saw signs of hope for the American worker. These developments may not herald a new birth for unions, but they are evidence that the campaign for just economic and labor policy can bear fruit.

The economy. American businesses saw an increase of 209,000 jobs in July. This marks the sixth straight month of job growth above 200,000. Meanwhile, the unemployment rate is at 6.2 percent, far below the 10 percent mark hit as a result of the Great Recession. The news is not all good: the average work week is less than 40 hours, and job rates among young people are near historic lows. This is a critical long-term problem. As the U.S. bishops write in their statement for Labor Day 2014, “Meaningful and decent work is vital if young adults hope to form healthy and stable families.”

Fast-food ruling. A one-sentence ruling by the National Labor Relations Board in July could mark a major breakthrough for labor organizers. Commenting on 43 labor suits filed against McDonald’s since 2012, the board’s general counsel held that the chain was jointly responsible for employment practices along with its franchise owners. For years McDonald’s and other large retailers have sought to distance themselves from the labor practices of their local operators. The long-term effects of the ruling are unclear, but they could help fast food workers who are seeking to unionize. It will be more efficient and potentially more fruitful to bargain collectively with a multinational company than with multiple franchise owners.

“Ban the box.” Many public and private employers have adopted a practice of requiring job applicants to check a box if they were ever convicted of a crime; in many cases, this means immediate disqualification for the position. The ban-the-box movement has challenged this screening practice in courts across the country. More important, it has persuaded many states and cities to adopt ban-the-box laws as good public policy. Leaders in both red and blue states are interested in ensuring that ex-offenders have a practical opportunity for employment and rehabilitation. Employers are still permitted to review criminal records later in the process, but banning this initial screening practice gives many applicants who made a mistake in their youth a fairer chance at consideration.

Minimum wage hikes. Though Congress failed to pass an increase in the minimum wage, 10 states passed increases in the 2014 legislative session. Nearly half the states have now implemented a minimum wage higher than the federal level of $7.25. Meanwhile, in February President Obama issued an executive order requiring federal contractors receiving taxpayer dollars to pay workers a minimum of $10.10 per hour. Some economists point to an increase in the earned income tax credit as a better way to help lower income families. We agree, and this increase should be pursued in Congress. But minimum wage increases on the state level are a healthy sign that local governments are responding to the needs of working families in their communities. Meanwhile, some American businesses, like Gap, are raising their hourly wages in an effort to lure more qualified workers.

In “Economic Justice for All” (1986), the U.S. bishops wrote about the challenges facing workers in a globalized economy: “In these difficult circumstances, guaranteeing the rights of U.S. workers calls for imaginative vision and creative new steps, not reactive or simply defensive strategies.” The positive developments outlined above are the fruit of creative thinking on the part of national and local labor leaders. Reliable, middle-class jobs may be hard to come by, but new networks of solidarity are taking root. A celebratory parade may not be necessary, but our support is. There is still work to be done.