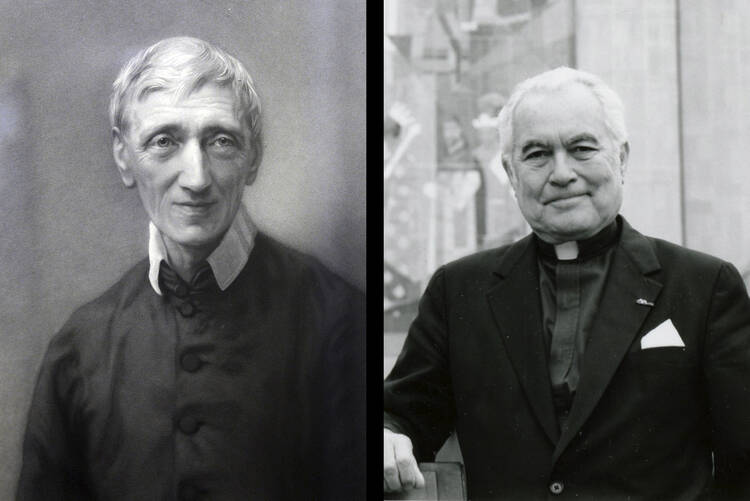

When anyone writes about the idea of a Catholic university today, or any other day out of the last century, there is always the temptation to repeat in substance what Cardinal Newman said in his incomparable classic on the subject. To suggest that there is something new or important to be said is to lay oneself open to plenty of criticism and even denunciation.

I am about to take this risk, but before I do, let me say clearly that Newman happens to be one of my heroes, too. I cannot recall how many times I have read and admired his great essays on the idea of a university. Yet it did occur to me recently, while harried by the many developmental and administrative problems that face a university president today, that Newman, in fact, never did create the university he wrote about, nor did he have to administer it.

There are many historical reasons to explain this, but it remains a fact that it is easier to write about what a Catholic university should be than to create and administer one in reality—to bring the total idea into being.

There is another cold fact that is often overlooked by those content to concede the last word to Cardinal Newman. Think of what our world is today in comparison with the world in which Newman wrote. Newman foresaw trouble, but hardly could have imagined all the trouble that actually occurred. Politically, the Pax Britannica has been followed by two devastating world wars, and by a militant philosophy antithetical to all that Newman’s world accepted. This same perverse philosophy now ruthlessly governs one-third of mankind and covets the rest. We have also seen another third of the world come to new political independence and strong nationalistic autonomy, with the revolution of rising expectations strong in the souls of millions. Then there is the Cold War, another modern reality that constantly erupts in local volcanic action, as widely separated as Cuba, the Congo and Vietnam.

Economically, we have had the Industrial Revolution and all of its aftermath. Scientifically, there has been yet another revolution which might successively be categorized as the motor and electric age, the nuclear and electronic age, and now, most recently, the space age. Space has shrunk, time is compressed: “around the world in eighty days” becomes around the world in eighty-odd minutes. Now for the first time in human history—again viewed not as a few thousand, but some hundreds of thousands of years—man can liberate himself from those ancient evils of ignorance, disease, grinding poverty, homelessness and hunger—or he can utterly destroy himself and all that he has created in the name of culture and civilization.

Let us not chide Cardinal Newman for writing in the middle of the 19th century instead of the middle of the 20th. But also let us not assume that what he had to say then, about a human institution in a particular historical situation, had absolute and unconditioned validity for all such institutions in all times.

Let us not chide Cardinal Newman for writing in the middle of the 19th century instead of the middle of the 20th. But also let us not assume that what he had to say then had absolute and unconditioned validity for all such institutions in all times.

Am I saying that the substance of the Catholic university changes from age to age? By no means. But I am saying that the mission of the Catholic university is also redemptive, and that what needs redeeming today is quite a different kind of world from Newman’s. The man to be educated is the same, but what he must be prepared to face is a world unimagined in Newman’s day. Newman is still with us, however, for he portrayed the university as “not a convent, not a seminary; it is a place to fit men of the world for the world.”

Teaching and learning were most essential to Newman’s university. They are still essential today, but what has been learned in certain areas since Newman would fill a new library with millions of volumes yet unwritten in his day. Research has grown by a factor of hundreds of thousands, if not millions. Over ninety percent of all the scientists who have lived during the course of human history are living today. And practically all of the behavioral scientists in the world’s history are still alive. Many legitimate new academic disciplines are born each decade, such as astrophysics and cybernetics.

Something else has taken place in recent years, almost without university people realizing it. The university has been drawn, through its faculty, administrators and students, into this new world in which we live. University people from America are scattered everywhere in the world today—founding new universities in Asia, Africa and Latin America; planning the ancient city of Calcutta’s new development; beginning the first systematic research in rice in the Far East; testing the depth of the ice in Antarctica and the composition of the earth’s crust in the ocean depths; studying native languages in New Guinea; planting new breeds of corn in Mexico, Colombia and Chile; digging up subhuman fossil remains in Tanganyika; advising a new Nigerian government on its legal system; and doing myriad other domestic and foreign tasks undreamed of in Newman’s age.

Should we say that this is bad, that the ivory tower has been defiled, that the government should send all the university people back home? And when they get home, should they be forbidden to confront their students with the monumental and unprecedented problems that face modern man all across the world? Should we keep the university isolated from the changing times and restrict ourselves to developing the idyll of knowledge for knowledge’s sake envisioned by Newman?

I am sure that there are some who would answer: “Yes, by all means.” If you do not answer yes, then you have the difficult problem of balancing the university and the times without losing the university in the balance. If this can be done, then the university, especially the Catholic university, becomes one of the most important institutions of our day.

To justify this last statement, I must reveal at least one assumption about the Catholic university with which Newman would heartily agree, as would some of his Anglican contemporaries, especially Dr. Pusey—and, it might be added, the present president of Harvard, who bears the same name. This assumption is that somehow, some way, theology and philosophy must effectively play an important role in the intellectual life of a university in our times.

Many ask in our day: Why a Catholic university? What unique contribution has it to offer? It is no mere chance that Newman, faced in his time with this same question, began to consider, first of all, three key subjects: theology as a branch of knowledge, the bearing of theology on other knowledge, and the bearing of other knowledge on theology. I shall not repeat what he had to say on these matters, but I do say that his remarks are relevant today, indeed even more relevant than they were in his own day, a century ago.

Someone asked me recently: “What is the great problem for the Catholic university in our modem pluralistic society?” I was obliged to answer that the modern Catholic university faces a dual problem. First, because everything in a pluralistic society tends to become homogenized, the Catholic university has the temptation to become like all other universities, with theology and philosophy attached to the academic body like a kind of vermiform appendix, a vestigial remnant, neither useful nor decorative, a relic of the past. If this happens, the Catholic university may indeed become a great university, but it will not be a Catholic university.

The second problem involves understanding that while our society is called religiously pluralistic, it is in fact, and more realistically, secularistic—with theology and philosophy relegated to a position of neglect or, worse, irrelevance. Against this strong tide, the Catholic university must demonstrate that all the human problems which it studies are at base philosophical and theological, since they relate ultimately to the nature and destiny of man. The Catholic university must strive mightily to understand the philosophical and theological dimensions of the modern problems that face man today, and once these dimensions are understood, it must show the relevance of the philosophical and theological approach if adequate solutions are to be found for these problems.

It goes without saying that the Catholic university cannot fulfill this essential function in our day unless it develops departments of philosophy and theology as competent as its departments of history, physics and mathematics. We cannot adequately understand philosophical and theological dimensions unless we have in the university talented philosophers and theologians, fully skilled in their science, as cherished as other scholars on the faculty, and deeply involved in the full range of university intellectual endeavor. At this point, we might recall with gratitude that Newman did write a book on the development of dogma.

It has been alleged that the university is cheapened by contact with modern reality in all its complexity. I would agree, if this means that the university is looked upon as a kind of service station to train people in superficial skills like hair-dressing, fly-casting and folkdancing. There are, however, modern realities that fully challenge the university as an institution dedicated to teaching and learning, in the context of the age in which it lives.

Can the university, its faculty, students or administrators be indifferent to such problems as racial equality, demography, the world rule of law, the deteriorating relationship between science and the other humanities, the moral foundations of democracy, the true nature of communism, the understanding of non-Western cultures, the values and goals of our society, and a whole host of other human problems that beset mankind caught in its present dilemmas of survival or utter destruction, life or death, civilized advance or return to the Stone Age? These are real problems—of intellectual content, of urgent consequence, of frightening proportions. Where are they going to be studied in all of their dimensions, and where are truly ultimate solutions to be elaborated, if not in that one institution that is committed to the mind at work, using all the disciplines and intellectual skills available?

The truest boast of the Catholic university is that it is committed to adequacy of knowledge, which in effect means that philosophy and theology are cherished as special ways of knowing, of ultimate importance. If, then, philosophy and theology do not in fact give special life and vigor to the Catholic university of today, we will not be faithful either to the ideal that Newman so well enunciated, or to the very special challenges of our times. They are times which provide an unparalleled opportunity for the Catholic university really to come of age.