A Jesuit friend and I stood in a snow-covered field near Midland, Ontario, and we were silent. It was very cold. In the distance, through swirling snowflakes, we could see a tall wooden cross. We were at St. Ignace, the site of a settlement founded by French Jesuit missionaries in the 17th century. We were also standing where two of these Jesuits, Sts. Jean de Brébeuf and Gabriel Lalemant, were martyred. It was intensely moving to stand with a Jesuit friend on the spot where two other Jesuit friends met their death.

I was visiting in Toronto to speak at Regis College, the Jesuit theology school, and the next day my friend and I decided to drive to the Martyrs’ Shrine, a place I had wanted to visit ever since entering the Jesuits. There are, in fact, two such shrines, built on or near the places where the North American Martyrs were killed during their ministry among the Huron-Wendat peoples in New France. In addition to the shrine in Ontario, there is another shrine in Auriesville, on the site of a village founded by the Jesuits in upstate New York. This shrine commemorates the martyrdoms of Sts. Isaac Jogues, Jean de la Lande and René Goupil. The three were killed by Mohawks, who at the time were enemies of the Hurons.

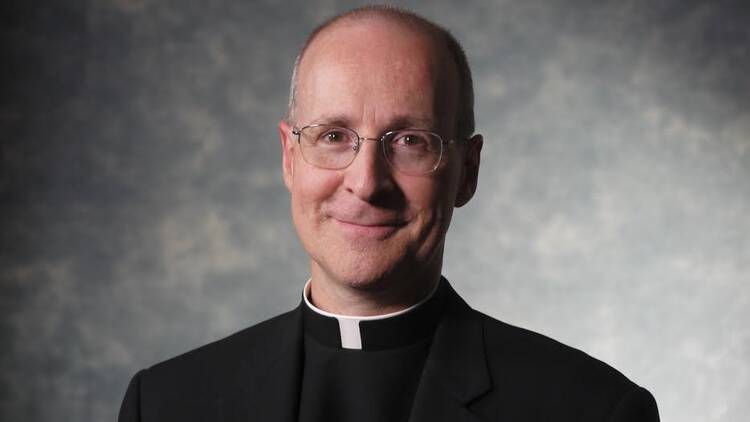

As Bernard Carroll, S.J., the director of the Canadian shrine, reminded us as we toured the grounds, it was not only Jesuits who were martyred; many Hurons who had converted to Christianity were also killed. So the Martyrs’ Shrine, which includes a reconstruction of the Jesuit village Sainte-Marie Among the Hurons, marks the legacy and martyrdoms of the native peoples as well. One of these, Joseph Chiwatenhwa, a catechist among his people, was the first non-European to make the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius in North America.

Today there is a tendency to downplay, criticize or even condemn missionaries of old. The argument mainly goes like this: Missionaries came to impose their Eurocentric ways on an unsuspecting people who would have been happier without Christianity. As tools of the brutal colonialist oppressors, the legacy is one of domination. As a result, as Emma Anderson, a history professor, opines in her highly critical history, The Death and Afterlife of the North American Martyrs, Catholic martyrs in the United States have become mainly “symbols of Catholic doctrinal purity and intransigence.”

Some of that reading is true: Sometimes missionaries supported, either wittingly or unwittingly, some of the more baneful practices of the colonial powers. But much of that reading is inaccurate. The Jesuit Relations, the collection of letters sent to France by the missionaries, paints a striking portrait of the lengths to which the Jesuits went to inculturate themselves. Learning the local languages was only the first hurdle. The Jesuits also needed to eat what to them was unpleasant food, sleep tightly packed next to one another in longhouses and endure uncomplainingly the biting cold and, later, torture. (The letters also note that one must never flag when paddling in a canoe with the Hurons.)

From the Relations one also receives a vivid picture of the Jesuits’ deep love for the people among whom they lived: “We see shining among them some rather noble moral virtues,” wrote St. Jean de Brébeuf. “You note, in the first place, a great love and union, which they are careful to cultivate….Their hospitality to all sorts of strangers is remarkable; they present to them, in their feasts, the best of what they have prepared, and, as I said, I do not know if anything similar, in this regard, is to be found anywhere.”

They suffered the severest privations to minister to people whom they both loved and admired. St. Isaac Jogues had his fingers either chewed or burned off, returned to France and then asked to return to New France. When people harshly criticize missionaries, I want to ask: Would you be willing to leave everything you know and travel across the world to live among people you’ve never met to share the good news of the Gospel with them?

As I stood in the cold, snowy field that day, I thought: Why were the North American Martyrs willing to face death? Not simply out of love for Christ, but out of love for the people to whom Christ had called them.