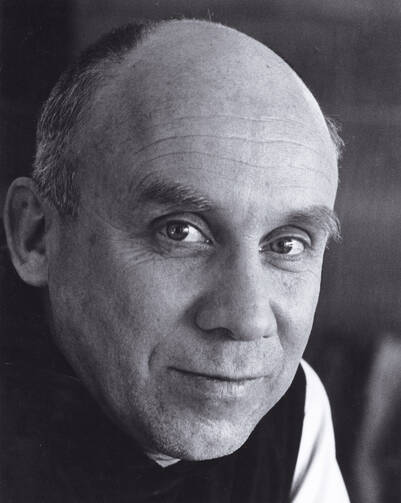

Jan. 31, 2015, would have marked the 100th birthday of the American Trappist monk and author Thomas Merton. But having died suddenly in Thailand on Dec. 10, 1968, while overseas to speak at conferences for Catholic monastic communities in Asia, Merton never lived to see a birthday beyond his 53rd. Yet his wisdom, writing and model of Christian engagement with the world continue to be relevant and timely.

Though Thomas Merton’s life was short, his output in terms of writing, poetry and correspondence was extraordinarily productive. The diversity of his work makes abundantly clear his importance in a number of areas related to Christian living, creative expression and social action. His continued popularity is confirmed by his perennial status as a best-selling author, a rare accomplishment. Many of his books have never gone out of print. The depth of his thought and spiritual genius is confirmed by the ever-growing bibliography of new articles and books written about Merton by scholars in diverse fields from theology and spirituality to American history, literature and peace studies.

While a general consensus appears to affirm the enduring status and legacy of Merton’s life and work, there are detractors who claim he is outdated and his appeal overstated. Among the most recognizable critics of Merton’s legacy and relevance is Cardinal Donald Wuerl, the current archbishop of Washington, D.C. In 2005, when Cardinal Wuerl was bishop of Pittsburgh, he chaired a committee that oversaw the production of a new United States Catholic Catechism for Adults, which was aimed particularly at young adults. Each chapter was to include a profile of an American Catholic whose life and work could serve as a model for Christian living. As the author and peace activist Jim Forest recalls in an afterward to his biography of Merton, Living With Wisdom, Cardinal Wuerl decided that the profile of Merton originally planned for the catechism should be removed from the draft text. Among the reasons given was that “the generation we were speaking to had no idea who [Merton] was.”

As both a member of the millennial generation and a professional scholar of Merton’s work, I take Cardinal Wuerl’s remark very seriously. In a sense, he is right. Not many of my peers—let alone people younger than I—know Merton in the same way that previous generations have, many of whom read Merton’s spiritual autobiography The Seven Storey Mountain and recognized Thomas Merton as a household name.

Yet in another sense Cardinal Wuerl’s reported view discounted the power of Merton’s true legacy. Merton does, in fact, resonate with the young adults who are introduced to his work, and it is the responsibility of the American church to remedy precisely what the cardinal was diagnosing. We must pass on to the next generation the wisdom and example of Merton so young Catholics can know him too.

As we celebrate the centenary of Merton’s birth it seems fitting to take a closer look at some of the ways Merton can continue to speak to us today. Several themes are especially timely, particularly for us millennials.

The Original ‘Slacktivist’

Conversion is arguably the most significant theme in Merton’s life. Those who came to know Merton first through The Seven Storey Mountain would recognize it as the thread that drives the narrative. Born to creative but largely unreligious parents, both of whom died before Merton turned 16, Merton grew up in an environment mostly devoid of religious practice or reflection. From the time of his memoir’s publication onward, Merton was hailed as a contemporary St. Augustine, whose “modern-day Confessions” highlighted how God’s grace breaks through an all-but-atheistic young man’s self-centeredness to inspire conversion to Christianity and eventually religious life. This is how Merton presented his story, which concludes with his entrance into the Trappist Order at the Abbey of Gethsemani in Kentucky.

But Merton’s conversion did not end there. Real conversion never ends. In fact, like Augustine’s Confessions, Merton’s memoir bears the marks of what literary critics call the “unreliable narrator.” We are presented with a compelling narrative, undoubtedly grounded in truth, but one that nevertheless emphasizes certain elements and overlooks others. With time on our side, as well as the resources of Merton’s journals, correspondence and the impressive official biography by Michael Mott, we know that his young adult life was probably much like the experience of the average college student. He questioned his beliefs, experimented with political associations, including Communism, developed his creative and artistic side, made lifelong friends, got into trouble and was shaped by his undergraduate mentors. If anything, Merton suffered most acutely from a closed worldview and lack of awareness of the needs of others, especially those outside his immediate circle.

This introspective worldview followed the young Merton into the monastery and can be seen in his early writings. It is not that he was misanthropic or dismissed those who suffered, but that he was preoccupied with his own spiritual journey. The 1940s and early 1950s saw the publication of books and essays by an enthusiastic young monk who wanted to share his faith with others, but the themes verged on the solipsistic: solitude, contemplation, asceticism, the monastic vocation. If we take Merton at his narrative word in The Seven Storey Mountain, then the conversion we are left with is one from the self-centeredness of “secular life” to the navel-gazing of “religious life.”

But as Lawrence Cunningham of the University of Notre Dame has written, “The period of the 1950s was a time of deep change in Merton’s thinking, a change radical enough to be called a ‘conversion’ (or, perhaps better, a series of conversions).” Merton’s experience of graced conversion did not end with his profession of religious vows and the donning of a Trappist habit. Rather, the shifts in Merton’s outlook on the world and God’s presence in it powerfully influenced his writing style and subject matter. It was as if a veil was lifted or his eyes were opened to the realities of violence, injustice and suffering around the world. He began to correspond with civil rights activists, world leaders and artists. He established what he would later describe in a letter to Pope John XXIII as “an apostolate of friendship” that allowed him to reach out to so many through his writing and correspondence.

Merton’s turn toward the world and the prophetic shift in his priorities seems to offer a timely lesson for today’s young adults. The neologism “slacktivism” has gained currency recently to describe the minimal efforts people engage in, often by means of social media, to “support” an issue or cause, but that have minimal or no practical effect. These produce mostly a sense of self-satisfaction from having done “something good.”

In an age of hyperconnectivity and rapid communication, young women and men are instantly aware of what is happening around the globe. The result is something like a preliminary conversion, a move toward awareness of something beyond oneself. But the slacktivism of today is not unlike the religious interiority of Merton’s early conversion. Over time Merton came to realize that he was (to be anachronistic) a slacktivist, someone who thought he was doing good for others but without taking the risk of putting himself in relationship with those he sought to help. Millennials can look to Merton as a model of someone who remained open to continual conversion, open to the challenge of God’s spirit, open to doing something more and risking much for the sake of another. He used his social location within the monastery, on the margins of society, to critique the injustices of his time—racism, nuclear armament, poverty—and then reach out to support, comfort and guide his readers and help to organize change.

Reading across Merton’s corpus, beyond The Seven Storey Mountain into his social criticism of the 1960s, can offer young people today a model for moving from slacktivism toward solidarity, from Tweeting about an issue toward doing something real about it.

Interreligious Dialogue

In October 1968, near the end of his life, Merton concluded a talk to a group of monks in Calcutta and with these now famous lines: “My dear brothers, we are already one. But we imagine that we are not. And what we have to recover is our original unity. What we have to be is what we are.”

Merton’s ongoing conversion opened him up to a variety of encounters and relationships that traversed the boundaries of the early 20th-century insular world of American Catholicism to engage in dialogue with people of different faiths and those with no affiliation at all. As early as the 1950s, Merton anticipated one of the monumental shifts that would emerge from the Second Vatican Council. Even today Merton is criticized by some who hold to a naïve reading of the patristic saying, Extra ecclesiam nulla salus (“Outside the church there is no salvation”) and believe that Merton overstepped his bounds as a Catholic priest by participating in dialogue with Muslims, Jews, Buddhists and Christians of other denominations. Some have even gone so far as to claim that Merton had “abandoned his faith” for some syncretic religious view. This could not be further from the truth.

There is nothing in Merton’s published works, nor in his private journals and correspondence, that would indicate interest in leaving the Catholic Church. In his 1966 book, Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander, Merton wrote:

The more I am able to affirm others, to say “yes” to them in myself, by discovering them in myself and myself in them, the more real I am.... I will be a better Catholic, not if I can refute every shade of Protestantism [or other faiths], but if I can affirm the truth in it and still go further.

At the root of Merton’s engagement with people different from himself was the sense of “original unity,” which he recognized bound all people together as children of God. He understood that he could not have an authentic conversation about faith with others if he did not have a firm commitment and deep love for his own tradition. Before Vatican II promulgated “The Declaration on the Relationship of the Church to Non-Christian Religions,” Merton already understood that “the Catholic Church rejects nothing that is true and holy in these [other] religions” (No. 2).

There is much that can be said about the still timely insights Merton presents to us about engaging other religious traditions. Perhaps the most pertinent is the need to live honestly in the tension between maintaining one’s own faith commitments and humbly learning from the experiences of others, all the while holding onto the belief that we are indeed, somehow, “already one.”

The Dalai Lama wrote in an op-ed in The New York Times in 2010, “While preserving faith toward one’s own tradition, one can respect, admire and appreciate other traditions.” He went on to explain that it was none other than Thomas Merton, with whom he met personally in 1968, who offered him this insight. “Merton told me he could be perfectly faithful to Christianity, yet learn in depth from other religions like Buddhism. The same is true for me as an ardent Buddhist learning from the world’s other great religions.” For Merton then, as for the Dalai Lama today, compassion for and personal encounter with people of other faiths does not diminish one’s own religious convictions—if anything, it strengthens them. Merton shows us as much by living out what he came to realize was his “vocation of unity,” to borrow a phrase from the Merton scholar Christine Bochen.

The Potential Appeal

Merton continues to speak a prophetic word to us today, but who is listening? Cardinal Wuerl may be correct that Merton is not as popular as he once was, but it is not because Merton does not appeal to young adults. Courses on Merton’s life and work are taught at colleges and universities around the United States today. The International Thomas Merton Society (on whose board of directors I currently serve) established the Robert E. Daggy scholarship program in 1996 to fund young adult participation at the society’s biennial conference. Set up by the late Rev. William Shannon, a renowned Merton scholar and the first president of the Merton Society, the scholarship has helped hundreds of young women and men delve more deeply into the popular and scholarly discussions about Merton’s life and work. My own travels speaking around the country and abroad offer anecdotal confirmation that when young adults are exposed to Merton’s writings and thought, they are captivated and often can relate to his experience of conversion, his openness to the diversity of others and his radical commitment to social justice and peace.

Merton’s writings are having an impact in a variety of locations and among diverse populations. There are currently 43 local chapters of the Merton Society and more continue to spring up, especially in Europe. But perhaps the most unexpected chapter is the one in the Massachusetts Correctional Institution in Shirley, Mass. Founded in 2013 by the retired educator and Merton enthusiast John Collins, the chapter is an outgrowth of a talk he gave about Merton at the inmates’ request. In an interview with The National Catholic Reporter, several of the incarcerated men—some who have been in prison for decades—spoke about the significance of reading Merton. Joseph Labriola recalled being in solitary confinement, discovering a copy of Merton’s New Seeds of Contemplation in his cell and reading out his cell’s window to other convicts. One prisoner, Timothy Muise, said that the Merton group “affords men the opportunity to change, to re-evaluate their life in God’s light.”

The increasing diversity of Merton’s readership is clear evidence that he is neither outdated nor irrelevant. It would seem that a century after his birth, Merton still has much to offer the church and world, and there is no indication that his reflections on peacemaking and interreligious dialogue will be outdated anytime soon. His wisdom speaks deeply to the hearts of those who encounter it. One can only imagine the possibilities that another century of his influence may have in bringing us all closer to that “original unity” about which he speaks, helping to lead us to recognize that “what we have to be is what we are.”