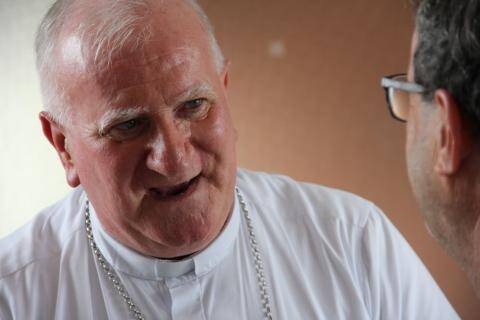

A delegation representing Jesuit ministries in the United States and Canada met with Bishop Michael Lenihan, O.F.M., of La Ceiba, Honduras, on Sept. 10, 2013. Bishop Lenihan worked in Honduras from 2000 to 2009 and then returned in 2012, when he was made a bishop. Luke Hansen, S.J., participated in the group conversation and edited the transcript for clarity and length.

What can you tell us about the expansion of mining interests in Honduras?

The Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace recently published a document on the love of creation and the need to protect mother earth and not to abuse and exploit it. There has to be dialogue and respect for the people. In this region there has not been any respect or dialogue with the people. Armed people pressure the landowners to sell their land. That is the big problem here.

We entered into dialogue with some of the miners in [the state of] La Atlántida. We brought the community together and had two meetings, but we did not succeed in stopping a prominent miner in the region. At one stage, he told us that if he could not win peacefully, he would bring people to help him enter by force. He said that to us privately at the meeting, but I think it is publicly known now. There is a lot of tension in the area. It is a very difficult situation. We have spoken with the people and tried to show solidarity with them. At times, in the face of the machinery of the state, it is hard to succeed and convince them not to exploit the land.

Could there be an independent environmental assessment?

We offered to have the universities do a detailed environmental impact study, but the mining companies produced a huge document saying they have already done this. But it is not very detailed. I would not trust the studies they have done.

The people are very, very worried because there are places where mining has already taken place, and they have done certain studies about the damage the mines have done to the water and the people. There certainly is a connection between the mining and the sicknesses the people have, but all of that is very, very quiet; it is not published. Obviously, if it were published, it would be very damaging for the mining company.

We have heard that the police have been very aggressive.

Yes. There were never police in that area and then, all of a sudden, the police came there. They said they were there to protect the people, but really their interest is very much against the people; it is protecting the interest of the miners. From what we can gather, there has been aggression, and they have treated people badly.

How did the diocesan statement about mining come about? Have you had any positive response from the average Catholic about this?

The letter came after a lot of debate. We let the ideas mature. We took out certain things, added certain things, and in the end we felt it was the right moment to publish something. We decided that we will do something to support Father César [Espinoza] and denounce what we believe is unjust and support the people and be a sign of solidarity to the people who are suffering in the midst of that.

Overall, the response was quite positive and a lot of people congratulated us on the letter. One of the bishops down in Choluteca said he had a meeting with antimining groups, and he used some of our thoughts and reflections to speak to the people. The politicians, however, would be negative because they do not want the church getting involved on that level. There have not been threats to our lives or anything because I believe it was very balanced, very much based in the Gospel, church teaching and the Franciscan charism of love for creation. But when you touch people’s interest, there will be a negative response.

Have the church-sponsored political forums made a difference?

They have been very, very successful. We had a diocesan synod where we invited politicians and listened to them and also presented the voice of the church. We also asked them as party leaders whether they were willing to respect and work for the defense of the environment. Afterward we got them to sign a pact. The signing is one thing; in the end, it depends on who wins the election.

The politicians are very much aware of what the church thinks, so what has happened has been very, very good, because the church and other groups have spoken out and opposed the mining concessions. We need more and more groups to do the same. We are one voice in the midst of a very powerful group, so what can we do? But we do not give up hope. The hope is that the struggle to defend nature continues. As a Franciscan, I feel very much obliged to defend nature. St. Francis was a lover of nature. He is the patron of ecology, so I would be a traitor if I did not try to help the people and speak out against abuses and exploitation. This is why we went ahead with the letter. We hope the reaction will be positive at the end.

Is there any way that people in the United States can be in solidarity?

The main thing is to come and see and have an interest, to visit the people and listen to the people and see how they feel and how they think at the moment. I don’t really know, politically or diplomatically, how we can convince the government. The government says China has already given money in advance, so legally the country has to say, “This is yours,” and there is no way of stopping it at the moment. It was frightening and alarming when a person said “a thousand acres here and a thousand acres there.” The whole of Atlántida will become a mine. I don’t want to be a pessimist about everything. We don’t lose hope, and the fight continues to try to prevent them.

Why does Honduras have the highest murder rate in the world?

A lot of the violence would be related to drugs and gangs, though there is also common delinquency. Extortion is very strong in Honduras, and it results in a lot of businesses closing down. It is not good for the country. Another big factor is the lack of employment. There are two million unemployed people. When you have this many unemployed, they can use different methods to try to survive and live.

There has also been a lack of effort on the part of the government to improve the security of the country. There doesn’t seem to be any desire. Or is the government simply incapable? Has it gotten to the stage where it is out of control and nothing can be done? The police force is very, very corrupt. Are they part of the problem instead of being part of the solution? All of these factors do not help.

I just share from my experience of what I have lived and what I hear and see. I hope something can be done to stem the tide, because it seems that Honduras has been completely sold over to the miners. We hope this is not the case.

Editor's Note: Read more about what the Jesuit delegation learned in Honduras in "Down to Earth," by Luke Hansen, S.J., and see photos from the trip here.