Pablo Picasso spent the summer of 1910 in Cadaqués, Spain. Among the paintings he did there were several that took his cubism to an almost entirely abstract extreme. In “Woman With a Mandolin,” for example, both the figure and the instrument are scarcely legible. His dealer found the work “unfinished,” and Picasso never again flirted so daringly with abstraction. “There is no abstract art,” he later said. “You always have to begin with something. Afterwards you can remove all appearances of reality, but there is no danger then, anyway, because the idea of the object will have left an indelible mark.”

Early in January of the next year, Vasily Kandinsky and his new friend Franz Marc attended a concert of Arnold Schoenberg’s radically atonal music. Both were exhilarated by the daring of the performance, though most of the audience was entirely baffled. “Can you imagine a music,” Marc wrote to a fellow artist, “in which tonality (the adherence to any key) is completely suspended?” In it he heard deep resonances with Kandinsky’s work and thought. Kandinsky had hesitated to embrace the elimination of the object, but after hearing Schoenberg he painted his feeling for the evening in “Impression III (Concert),” an exuberant riot of color with only faint suggestions of gathered figures.

By the end of the year he had exhibited the entirely abstract “Composition V,” a major visual statement of his view that “the most advanced art offers emotions that we cannot put into words.” “Since that time,” he wrote, “I know what undreamed-of possibilities…color conceals within itself.”

The following summer (1912) the French painter Francis Picabia took a long road trip with the musician Claude Debussy and the poet Guillaume Apollinaire. While returning to Paris, the three friends fell to discussing the possibilities of nonfigurative art. Taking up the challenge, Picabia pressed the point: “Are blue and red unintelligible? Are not the circle and the triangle, volumes and colors, as intelligible as this table?” Back in his studio he set to work on a large canvas of arching russet, brown and black forms springing up wildly from a barely suggested planar ground. The colors recalled Picasso’s Rose Period, but the rough handling of the paint and the pure abstraction were Picabia’s alone. He exhibited “La Source” (“The Spring”) that October in the Salon d’Automne, in which František Kupka and Fernand Léger also showed canvases that were purely abstract. It was the public début of abstraction in Paris. Early on, Kandinksy, Apollinaire and others spoke of it as “pure painting.”

The story of this startling shift as it spread through Europe and the United States as well is being presented in the exhibition Inventing Abstraction, 1910-1925, which runs through April 15 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Well over 350 works by 84 artists are gathered. At the entrance a large diagram indicates how the artists interacted with one another, with 13 of them having over 24 “connections” within the network. “Network thinking,” in fact, is the hermeneutic key to appreciating how so radical a shift of consciousness was possible. What was once unthinkable and then became universal, argues Leah Dickerman, the show’s curator, arose from social interaction, “a distinctly modern interconnectedness.” She draws on sociology to propose that “many investigators converging on the same finding [is] a common pattern of scientific discovery.” The art, moreover, is by painters and poets, sculptors and musicians, photographers, choreographers and filmmakers. Abstraction, we learn, was “a cross-media imperative.”

After key works by Picasso, Kandinsky, Kupka, Picabia and Léger, the exhibition proceeds chiefly according to local associations. A wall of adventurous Americans is placed diagonally across from their compatriot Morgan Russell’s immense “Synchromy in Orange: To Form” (1913-14). Nearby, the Italian Futurists, including Giacomo Balla and Gino Severini, refuse to believe that paint on canvas and words on paper cannot move. Gathered around Wyndham Lewis in Britain, the Vorticists claimed their own mantle of leadership.

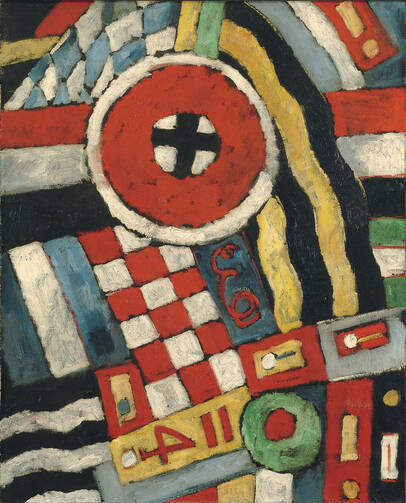

The revelatory heart of the show is a space bounded by two walls, one showing nine paintings by the Russian Kazimir Malevich, the other with three by the American Marsden Hartley. The Malevich canvases, severe geometric forms on white grounds and all from 1915, were shown that year in Petrograd (now St. Petersburg). There Malevich announced his theory of Suprematism—his “new painterly realism” that claimed supremacy over the forms of nature. Exquisitely balanced, the relatively small paintings convey an aspirational spirituality. They seem ready to rise from the wall into some boundless sky—and risk being icy. The Hartleys, on the other hand, one a glowing tribute (c. 1914) to the influence of both Delaunay and Kandinsky, the other two (about the same year) from a series painted as covert declarations of love for a young German officer, are dense, detailed and, in the case of the officer paintings, all but feverish. Between the two walls rises Constantin Brancusi’s “Endless Column, Version I” from 1918. The space throbs with the extreme possibilities of abstraction.

A visitor to “Inventing Abstraction” may wonder at this point: “Where is Mondrian?” And then he suddenly and brilliantly appears, in a beautiful, white-walled bay with 11 paintings. These works range from the still (barely) representational “Trees” of 1912 to several canvases in which figure and ground merge into an all-over pattern of interlacing shimmers (from 1913 to 1916) and on to the fully achieved Neo-Plasticism of 1920, with its reduced palette of primary colors plus black and white deployed in endlessly inventive, grid-like patterns that defined the artist’s practice for the rest of his life.

As the show draws to a close, with mesmerizing films of the choreographers Mary Wigman and Rudolf von Laban and then a choice collection of Dada reliefs by Hans Arp and equally strong pieces by his wife, Sophie Taeuber-Arp, I noted how unusually well represented women are here on the sixth floor of the museum. It was the reality of the time. In Paris, New York, Munich, Milan, Moscow, London and Zurich, the radically new way of making art was a shared one.

My one reservation about the show is not about the splendid selection of art Ms. Dickerman has made for us. What I find less persuasive is the exhibition’s accompanying narrative. With Marcel Duchamp as her most explicit critical supporter, Ms. Dickerman understands abstraction as heralding the demise of painting in its traditional form. Duchamp seemed to intuit, she writes in the catalogue, that “the emergence of abstraction spelled the demise of painting as a craft and its rebirth as an idea,” a new “understanding of art not as illusion but as idea.” The “pure” painters and musicians and poets all needed explanations of what they were about, to assure that their work still had meaning. Manifestos multiplied and advocacy ascended. (One thinks of the art critic Clement Greenberg, later, canonizing Jackson Pollock.) And so “image-making and writing emerge as simultaneous and interrelated practices with a displaced relationship to one another.” But the abstract is the ideal.

Despite all the exhilarating work offered in this show, I am still not inclined to think that Picasso and Matisse can be seen as representatives of a bygone era, nor even that contemporary painters like Gerhard Richter and Anselm Kiefer are “timely” only when they dispense with objects. It is an unfortunate disjunction to oppose abstraction and representation, not to mention an oversimplified epistemology to think that painting ever existed simply objectively for itself, without appreciative viewers. Who has ever looked for any length of time at Cézanne’s “Bather” and not realized that you are not confronting some boy from Provence but rather the very idea of a bathing boy?

And then there’s the question whether “the death of god,” briefly noted in the catalogue as one of the factors preparing the ground for “pure painting,” made representation of a created world any less compelling. Couldn’t the new art’s “constructive” celebration of color, form and space be another way of celebrating a created order’s infinite variety and value? But those are questions for another time—after you have delighted in the revelations of “Inventing Abstraction.”