In 1959, Pope John XXIII redesignated the Diocese of Galveston as the Diocese of Galveston-Houston, and elevated Houston’s Sacred Heart parish to the unusual status of co-cathedral, shared with the St. Mary cathedral basilica in Galveston. As the population of Houston boomed, more than doubling in the second half of the 20th century, the diocese outgrew the space, and in 2002 Pope John Paul II approved the design of a new co-cathedral of the Sacred Heart. Ground was broken for the new building in April 2005, just three months after the death of John Paul II.

This year on the Second Sunday of Easter, or Divine Mercy Sunday, the day these two popes were recognized as saints, I visited the co-cathedral of the Sacred Heart, a structure that was in a special way touched by and even embodies their pontificates. For this is a church of the Second Vatican Council, a church of liturgical reform in—if I may say so—the spirit of the council fathers, and certainly in the spirit of St. John XXIII and St. John Paul II. It is a church of aggiornamento, built not according to a hermeneutic of discontinuity, but rather—as Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI characterized the program offered in St. John XXIII’s opening speech at the council—a “hermeneutic of reform.”

Every detail is somehow both classical and contemporary. The clean, angular edifice, rising in straight, unembellished lines, does not look out of place beside the skyscrapers of downtown Houston. And yet the luminous limestone facade, the large center window and the white marble entryway all exude a warm and gentle peace amid the clamor and rush of city life. The simple gold cross rising against a big blue Texas sky proclaims a serene and confident victory. Here is a place that is in the world—but not of it.

Three tall, wooden doors are the only dark accents on the building. Against the stone, they seem soft. Standing as they do among the white and gold, their darkness beckons the passerby, almost as a secret pathway into whatever mystery is contained within.

As one approaches the entryway, three relief sculptures become visible in the limestone above the doors, with Christ enthroned in the center, surrounded by a moon, sun and stars of gold. On either side are saints adoring the majestic Lord of all creation. Upon entering, one sees the cruciform shape of the co-cathedral in expansive depth. The high windows, in sets of three, are clear but for a solitary stained-glass angel in each middle window; the result is that the interior limestone walls glow, and the space is filled with natural light.

The angular lines are broken only by the arches of the sanctuary, set off in light red marble. Underneath the high center arch, Christ hangs on the crucifix, towering majestically above the altar, against a background of rippling gold. The effect is wonderfully paradoxical and mysterious: there hangs Christ, shining victoriously in death.

Below is the marble altar, in a darker hue than the arches, giving it a gravity that draws the eye and makes it the clear center of the sanctuary, the blood red color reflecting its history and meaning. Above the sanctuary is a dome, remarkable in its simplicity. It cascades upwards in white steps, ringed with mostly clear stained-glass windows, and at its apex is a window with a dove descending. For all the open light in this co-cathedral, it is clear that it is no ordinary sunshine, but the light of God.

As one approaches the sanctuary, nothing prepares the visitor for the glorious moment in which the transept walls come into view. On the right side is a sculpture of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, on the left a sculpture of the Blessed Virgin, both wrought in soft white stone, backlit and suspended, as if floating, against the same rippling gold backdrop as the sanctuary crucifix. In an instant, one is surrounded by white, gold and light. It is more than an image; it is an experience of the church as body of Christ and communion of saints.

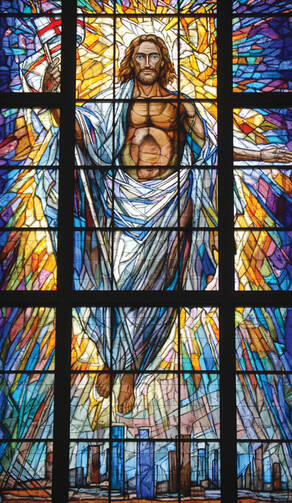

And then, in the opposite direction, there on the front wall is a vast rectangular stained-glass window of the Resurrection. All the white and gold, which until this moment seemed complete, now pales before the kaleidoscopic Christ, enrobed in massive organ pipes, bursting upon you. It brings to mind the passage in St. Augustine’s Confessions in which, after marveling at the light before him, he finally turns around to find that Christ, the source of the light, was behind him the whole time. There is surprise and delight, but also intelligibility and clarity. The Resurrection window shines as an answer to a question we did not even know we were asking—like God’s grace.

All this is so familiar and yet so new. Everything that you expect to find in a cathedral is here, but not in the way that you expect to find it. The Stations of the Cross stand out in silver bass relief. There is nothing sentimental or pietistic about them; they are real, rugged works of art that confront you and demand that you meet them on their journey. The statues of the saints along the walls are executed at the precise meeting point of mannerism and realism. They are stylized, but they are real. They are both like and unlike us. And among their ranks are many of our day’s beloved saints: St. Thérèse of Lisieux, St. Elizabeth Ann Seton and, perhaps most fittingly and beautifully for a diverse city, St. Juan Diego, depicted with the apparition of the Virgin of Guadalupe on the front of his cloak. The message is clear: their holiness is attainable; their holiness is our holiness.

This is a church of “the new people of God” described in the “Dogmatic Constitution on the Church.” But it is also a church of the “Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World,” which recognizes, meets and invites all people in the universal metaphor and shared language of light. It is humble and glorious, simple and sublime.

It was a fitting place to celebrate Mass on this particular Divine Mercy Sunday. For, architecturally and liturgically, the Sacred Heart co-cathedral embodies the spirit of the two great saint-popes, whose pontificates began and completed its construction.