I dare speculate that few religion courses at Catholic universities cover “Pussy Riot’s Theology,” “Nit Grit ’Hood Theology” and the spiritual significance of pop star Lorde’s ubiquitous tune, “Royals.” These themes, however, resonate with students in a course I developed and taught at the University of Detroit Mercy.

It began in 2008, when I spent a very intellectually and musically stimulating weekend at St. John’s University in Collegeville, Minn., with some fellow theologian-musicians. We played music and talked about God and discussed how these passions fit together in our lives. It’s a topic I eventually tackled at book-length (see sidebar), and I began to think that the conversation might be a fruitful one to have with my students as well. In the fall of 2013, after my proposal for a new class had been accepted, 11 students registered for the class called “Rock, Hip-Hop and Religion.” It was the perfect number of students for a course that relied on a lot of listening, both to music and to each other during discussions.

Serious academic attention to popular music and religion has grown significantly in recent years. Some professional theology and religious studies conferences include specialty groups in this area, and several scholars have delivered papers about the intersection of popular music and the sacred. At the meeting of the Catholic Theological Society of America in 2011, for example, the theologian Michael Iafrate presented his paper, ‘“I’m a Human, Not a Statue’: Saints and Saintliness in the Church of Punk Rock.” Calvin College in Grand Rapids, Mich., holds one of the most credible and stimulating conferences on religion and music in the United States every two years, and it has attracted a wide range of important thinkers who continue to add to the ever-growing corpus of work in this field.

Figuring out which books to use for my course, which articles to read and how much I needed to dive into historical theological ideas to buttress our class discussions was a very difficult task. I ultimately chose three books for the course (see sidebar). And I supplemented readings from these texts with a variety of articles from an array of sources like Rolling Stone, America, Books and Culture and The Chronicle of Higher Education.

The students were all expected to analyze three songs. The process unfolded like this: each student played a song for the class and then offered a five-minute analysis of the theological and spiritual themes in the song. This was not simply an exegesis of song lyrics but rather a more in-depth discussion of how the various parts of the song (rhythm, timbre, tempo, instrument choices, tone and, yes, lyrics) all contribute to communicating something about the “sacred.”

The presentations were at first a bit superficial, but soon the students were able to integrate the reading material, become more facile with theological language and offer more substantive explanations. On a few occasions students became unexpectedly choked up while speaking about the songs—the emotional connection with the music could not be repressed by typical academic mores.

I soon learned which themes from the readings captured the imagination of these students. Three ideas were particularly important to them. The first was nit grit ’hood theology, as outlined by Daniel White Hodge in his book The Soul of Hip Hop. Hodge explains that in the face of racism, urban decay and diminishing opportunities for African-Americans, simplistic theological responses are not sufficient. Why ask God to bless us with more when so many have nothing? Why are innocent people being murdered while criminals are thriving?

Hodge points to the deceased hip-hop artist Tupac Shakur as one who professed a nit grit ’hood theology, even in the face of criticism from his community. He, like many in his generation, demanded a deeper analysis of complex social justice issues, showed a strong concern for those who are often forgotten and expressed an appreciation for building a sense of community in one’s neighborhood. As Hodge states, “Let’s pray about it” is an insufficient response. There must be action.

The second important theme was the role of religion and spirituality in the history of rock and roll, especially as represented by Motown records. I would have failed as a teacher of music and religion in the city of Detroit had I not organized a field trip to the Motown Museum, the home of the original Studio A, created by Barry Gordy. The young African-Americans who became the early stars of Motown came largely from an inner-city evangelical Protestant community. This is reflected in their singing style and the social justice themes of their songs—most notably in Marvin Gaye’s classic album “What’s Going On?”

The use of the tambourine, which plays a prominent role on several Motown hits, was borrowed from black church choirs. Motown also played an important role by recording numerous African-American religious and political leaders and releasing their speeches for the public. Most famous among these was an early version of Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered in Detroit in 1963.

Finally, one task of this course was to help students reflect on how their musical tastes can be integrated with their spiritual practices and religious beliefs. One tool for this is the film “Taqwacore,” a documentary about young adult Muslims who play in a punk rock band. The overarching theme of this film is the clash of cultures—immigrant parents attempting to preserve traditional customs and their “Americanized” children who explore what it means to be a part of a U.S. culture that fears them in the post-9/11 era.

These tensions result in plenty of frustration for the young Muslim-Americans, many of whom were the same age as my students, and the anger and aggression expressed in punk served as the perfect medium for them. Few if any of my students had to face the struggles of the young Muslim punk rockers portrayed in the film, but the dynamic of wrestling with the oft-competing messages of popular culture and traditional religious dogma is one they found familiar.

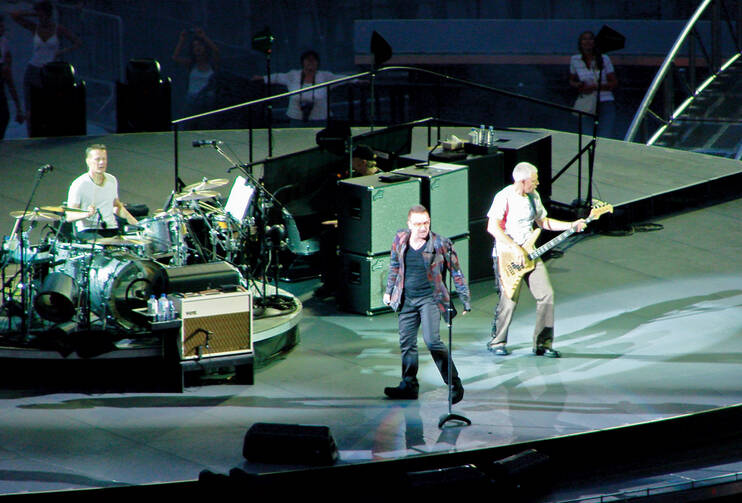

One of the persistent challenges of the course was in deciding how much historical and theological material to introduce. For example, if I play the song “Mothers of the Disappeared” from U2’s 1987 masterpiece “The Joshua Tree” as an illustration of a song that addresses a particular social justice concern, I cannot help but delve into the controversy surrounding U.S. foreign policy in Central America in the 1980s and the injustices suffered by tens of thousands in El Salvador and elsewhere. That would logically lead to the Salvadoran martyrs (the church women and the Central American University Jesuits especially) and the history and role of liberation theology in shaping the Christian perspective on God’s preferential option for the poor and suffering. Throughout the semester, my appreciation for my students’ musical taste grew. And I was pleasantly surprised by the depth of analysis each of them offered about the music they loved—and the theology they found within it.

Further Reading on Rock and Faith

Rock-a My Soul, by David Nantais (Liturgical Press)

The Soul of Hip Hop: Rims, Timbs and a Cultural Theology, by Daniel White Hodge (InterVarsity Press)

Secular Music and Sacred Theology, edited by Tom Beaudoin (Liturgical Press)

Personal Jesus: How Popular Music Shapes our Souls, by Clive Marsh and Vaughan S. Roberts (Engaging Culture)

Your Neighbor’s Hymnal: What Popular Music Teaches Us about Faith, Hope and Love, by Jeffrey F. Keuss (Wipf & Stock Pub)

Broken Hallelujahs: Why Popular Music Matters to Those Seeking God, by Christian Scharen (Brazos Press)

Call Me the Seeker: Listening to Religion in Popular Music, by Michael J. Gilmour (Bloomsbury Academic)

Resounding Truth: Christian Wisdom in the World of Music, by Jeremy S. Begbie and Robert Johnston (Engaging Culture)

Rock and Theology blog archives: www.rockandtheology.com