Adult stem cells, easily harvested from human bone marrow, umbilical cord blood and fat tissue, have a successful track record in treatments for more than 90 medical conditions and diseases, including sickle cell anemia, multiple myeloma cancer and damaged heart tissue.

Stem cells can be retrieved and used in treatments while doing no harm to donor or recipient.

So why do so many Americans, including some physicians, continue to champion research involving embryonic stem cells when this type of intervention has no documented cases of improving health and also requires the destruction of human life in its youngest form?

That question was pondered by David Prentice July 10 at the National Right to Life Convention during his presentation "Adult Stem Cells: Saving Lives Now."

Prentice, vice president and research director for the Washington-based Charlotte Lozier Institute—the education and research arm of the pro-life Susan B. Anthony List—reported that more than 70,000 patients throughout the world are receiving adult stem-cell transplants annually, with an estimated 1 million total patients treated to date.

"How many people have been cured using embryonic stem cells?" Prentice asked his audience. "Zero," he answered, noting that misinformation in the media and the Internet continues to promote "fairy tales" about the promise of embryonic stem cells in curing disease and being the elusive "fountain of youth" for mankind.

"You've got to destroy that young human being to get the embryonic stem cells," Prentice said of the over-hyped technology.

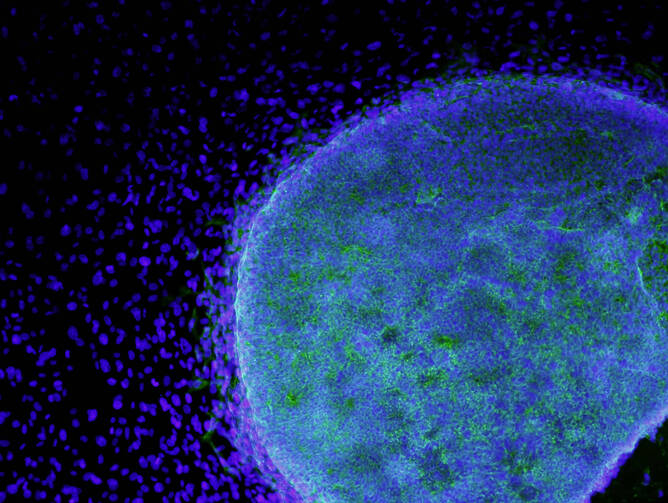

Conversely, adult cells—undifferentiated cells that already exist among the differentiated cells that make up specific tissues or organs—can be isolated and deployed to various parts of the body to regenerate and repair diseased or damaged tissue.

There is more good news about adult stem cells besides its ethical supremacy, Prentice said. Unlike embryonic stem cells, adult stem cells are readily available to the majority of patients.

Many types of adult stem cells can be harvested in relatively painless, outpatient procedures. For example, adult stem cells from bone marrow, once accessible only by deep needle extraction, can now be collected in a process akin to giving blood. Another source of stem cells - fat tissue - can be tapped via liposuction.

Also, despite being tagged as "adult," children can receive the therapy as early as the in-utero stage, and the donors of adult stem cells do not have to be adult at all.

"Babies are born with (adult) stem cells throughout their body," said Prentice, an adjunct professor of molecular genetics at the Pontifical John Paul II Institute for Studies on Marriage and Family at the Catholic University of America. "The umbilical cord that we cut off after the baby is born is rich in what we call adult stem cells."

Besides requiring the killing of human life, Prentice said, embryonic stem-cell research posed a major threat to women's health that went largely unpublicized during the height of the push for this technology in the first decade of the 21st century. Women between the ages of 21 and 35 were actively sought and handsomely paid for their eggs to keep pace with the demands of heavily funded research. To harvest a woman's eggs, the donor is given a regimen of hormones over a period of three to five days, Prentice said. Unforeseen side-effects included ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome, kidney failure and infertility.

"Some women have even died in the process," Prentice said.

Because of these and other ethical objections, France, Canada, Germany, Norway, Switzerland and about 25 other countries, excluding the United States, have banned human cloning, which uses living embryos for experimental purposes before killing them in the lab.

"We're actually behind the international curve here in the United States," Prentice said, noting that the FDA has hit a new low by looking into the possibility of approving the production of three-parent embryos -those involving cellular donations from one father and two mothers.

To offset the bad press—including public repugnance to the idea of "designer babies"—Prentice said private companies seeking funding for embryonic stem cell research have begun to refer to cloning in a less "science fiction" way—as "somatic cell nuclear transfer."

"It's kind of science run amok," Prentice said. "They're not actually correcting or treating anybody (with embryonic stem cells). They're talking about new individuals who will be genetically engineered to their specifications."

Current protections in place include the federal Dickey-Wicker Amendment, which prohibits the use of taxpayer dollars to create or destroy human embryos for experiments; and some states, including Louisiana, have banned research related to human cloning and human-animal hybrids.

As adult stem cell treatments gain credibility in science journals, insurance companies increasingly are covering the procedures, Prentice notes.

Interventions in more experimental phases of study, such as those treating spinal cord injuries, are less likely to be covered by insurance plans, he said.

"The bottom line is the adult stem cells are the ones that work—they're working now in patients," Prentice said. "I'm telling you all these (stories of success), but you're probably not seeing it in the news, right?"

Prentice said the website www.stemcellresearchfacts.org offers statistics and patient testimonials;information on current trials can be found at www.clinicaltrials.gov; and the Lozier Institute's website is www.lozierinstitute.org.