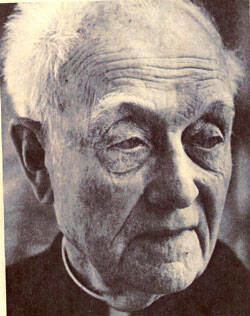

A major debate began in the U.S. Catholic Church with the publication 40 years ago by Msgr. John Tracy Ellis of his essay on "American Catholics and the Intellectual Life." In 1955 the 50-year-old Ellis was already a well-known figure as professor of church history at The Catholic University of America in Washington and managing editor of The Catholic Historical Review. Only three years earlier he had published a two-volume life of James Cardinal Gibbons that set new standards for clerical biographies and won wide respect among historians. Ellis's brief essay on American Catholic intellectual life, however, brought him more attention and created far more controversy than his magisterial biography of Gibbons. Forty years later the debate provoked by Ellis among U.S. Catholics still goes on, with results that are sometimes difficult to assess.

Ellis's 1955 essay was controversial because it was largely a criticism of U.S. Catholic universities and colleges for their failure to make a recognizable contribution to American intellectual life. Ellis took as his starting point a comment by Denis W. Brogan, the Cambridge political scientist who was an expert on both modern French and American history. Brogan had said in 1941 that "in no Western society is the intellectual prestige of Catholicism lower than in the country where, in such respects as wealth, numbers, and strength of organization, it is so powerful." More in sorrow than in anger, Ellis commented: "No well-informed American Catholic will attempt to challenge that statement."

Anti-intellectualism and Bigotry

Ellis offered a number of explanations for the backwardness of American Catholic higher education. Some of the reasons he mentioned were beyond the control of American Catholics, such as the anti-intellectualism of Americans in general, the persistence of anti-Catholic bigotry in the United States and the long-standing need of the American bishops to devote their limited financial resources to the elementary education of poor immigrants. But Ellis touched a more delicate nerve when he focused his attention on the intellectual shortcomings of the American Catholic community itself and criticized American Catholic scholars for their failure to cultivate a love of learning for its own sake.

Ellis took his fellow American Catholics to task for what he called "a betrayal of that which is peculiarly their own." As an example, he pointed to the irony that certain secular universities, such as the University of Chicago and Princeton University, were making a notable contribution to the revival of scholastic philosophy, while many Catholic universities "were engrossed in their mad pursuit of every passing fancy that crossed the American educational scene." At the other extreme, according to Ellis, were those Catholic educators who regarded the Catholic school almost exclusively as "an agency for moral development" and placed "an insufficient stress on the role of the school as an instrument for fostering intellectual excellence."

One of Ellis's most persistent criticisms of U.S. Catholic higher education was aimed at the multiplication of small and under-funded colleges with low academic standards. In 1955 there were over 200 Catholic colleges in the United States, and Ellis regarded the number as a liability rather than as an asset. Even more alarming, from his point of view, was the fact that the process seemed to be repeating itself on the university level. Ellis called this "our betrayal of one another." "By that I mean," he said, "the development within the last two decades of numerous and competing graduate schools, none of which is adequately endowed, and few of which have the trained personnel, the equipment in libraries and laboratories, and the professional wage scales to warrant their ambitious undertakings." The result of this proliferation of competing Catholic universities, said Ellis, "is a perpetuation of mediocrity and the draining away from each other of the strength that is necessary if really superior achievements are to be attained."

Still another theme that Ellis sounded was the failure of Catholics--and not only American Catholics--to support their scholars. One of the most poignant passages in Ellis's essay relates to the Rev. Philip Hughes, the English church historian. In 1954 the American Catholic Historical Association awarded Hughes its John Gilmary Shea prize for his three-volume history of the Reformation in England. Hughes told Ellis: "It is the first recognition I have ever had, and it is from my own. It touches me too deeply for me to find words to say all I feel about it." Ellis may well have been thinking of his own experience in America, when he added: "How many American Catholic scholars, both living and dead, could tell a similar tale of the failure of their own to recognize their scholarly accomplishments and to lend them their support?"

Bent Rules, Lower Standards

In his 1955 essay Ellis did not criticize any Catholic college or university by name, but it is clear that he was drawing upon his own less than happy experience with Catholic higher education in the United States. Ellis was a native of Seneca, Ill., a small farming village in the heartland of the American prairies. His college years were spent in another small Illinois village 40 miles away, Bourbonnais, where he attended Saint Viator College, a small institution operated by the Clerics of Saint Viator. Just how small Saint Viator was can be gauged from the fact that in 1927 John Tracy Ellis was one of only 16 people in the graduating class. There were some fine professors among the faculty, and no institution that produced Ellis and Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen—the foremost clerical orator of his day—could be deemed a failure, but Saint Viator was too small and too poor to become a quality institution. Unable to pay its debts, it closed its doors for good in June 1938. Many years later Ellis said: "Had I the power to bring Saint Viator College back into existence, and that with a substantial endowment, for a variety of reasons I should hesitate to do so."

After graduating from college, Ellis won a scholarship to The Catholic University of America, where he earned a doctorate in history under Msgr. Peter Guilday. As a graduate student—still a layman—Ellis quickly became disillusioned with the poor quality of the history department. In fact, he was so disappointed that he applied for admission to the University of Illinois and would have transferred there if he had been able to obtain a scholarship. Ellis's mentor, Peter Guilday, was a Louvain-trained historian whose specialty was American Catholic history. He was, however, directing Ellis's doctoral dissertation in medieval history, and Ellis quickly realized that Guilday was not qualified to supervise graduate work in that field. When Walter Ullmann, the distinguished British medievalist, later asked Ellis for a copy of his dissertation, he replied that there was none available and admitted, "I really blush whenever I look back on my immature efforts of 1930 in the doctoral dissertation."

After earning his Ph.D. degree in 1930, Ellis spent four years teaching history as a layman at several small Catholic colleges, including his alma mater, Saint Viator. In 1934 he entered the seminary; he was ordained a priest four years later. He then began his career as a priest-professor at The Catholic University of America. As a teacher, he discovered that he had to prepare his courses from scratch because his graduate studies had been woefully deficient in content. In July 1941, when Ellis was asked to replace Guilday as professor of American church history at The Catholic University, he first insisted on a years leave of absence, part of which he spent at Harvard University preparing himself for his new responsibilities.

There was still another personal reason for Ellis's critical assessment of American Catholic higher education, stemming from an unusual part-time job he had during his student days at Saint Viator College. He worked as secretary to John Maguire, C.S.V., who was not only vice-president of the college, but also secretary of the college accrediting committee of the National Catholic Educational Association. Ellis often accompanied Maguire on his visits to Catholic campuses and observed at firsthand how the committee would sometimes bend its rules and lower its standards in response to emotional appeals from college presidents and deans. "It was the opening chapter," Ellis said, "in a story of gradual disillusionment that deepened with the years, a story that reached a climax of sorts in May 1955"—that is, with the address that was published that fall in the Fordham University quarterly, Thought, under the title "American Catholics and the Intellectual Life."

Credentials of Truth and Honesty

In 1955 Monsignor Ellis fired the opening shot in the debate about the quality of American Catholic intellectual life, but he was soon followed by other scholars who echoed his criticisms and expanded upon them. Ellis himself made another notable contribution to the debate in 1966 with a lecture that was subsequently published under the title "A Commitment to Truth." It was an eloquent and erudite plea for intellectual integrity in Catholic scholarship. In that lecture Ellis quoted with approval the words of a still relatively unknown German theologian, Joseph Ratzinger, that what the church needed "are not adulators to extol the status quo, but men whose humility and obedience are no less than their passion for truth." Writing in the immediate aftermath of the Second Vatican Council, Ellis warned that it would be impossible for the church to realize the wonderful aspirations of the council "unless her teaching, her intellectual apostolate, her liturgy and worship, yes, and the lives of her sons and daughters, bear a note of authenticity and carry the credentials of truth and honesty."

By the time Ellis wrote "A Commitment to Truth," he had left The Catholic University of America for the University of San Francisco where he found both the physical and intellectual climate more conducive to his health. One colleague and admirer who commiserated with him on his departure from Washington was Dom David Knowles, Regius Professor of Modern History in Cambridge University. "The university will feel it too," Knowles said of his departure, because, he explained, "for the majority of English academics, yours was the most familiar name, and indeed throughout the English-speaking Catholic world, as that of one who spoke out for true freedom, i.e., truth, whatever the opposition."

Few historians have the satisfaction of shaping history as well as writing it, but John Tracy Ellis managed to do precisely that in his deceptively brief essay of only 46 pages. Forty years ago that essay provoked a good deal of soul-searching among American Catholics. It is well worth reading today, and will continue to be so, at least as long as there are Catholics who still believe that a love of learning for its own sake is an authentic Christian virtue.