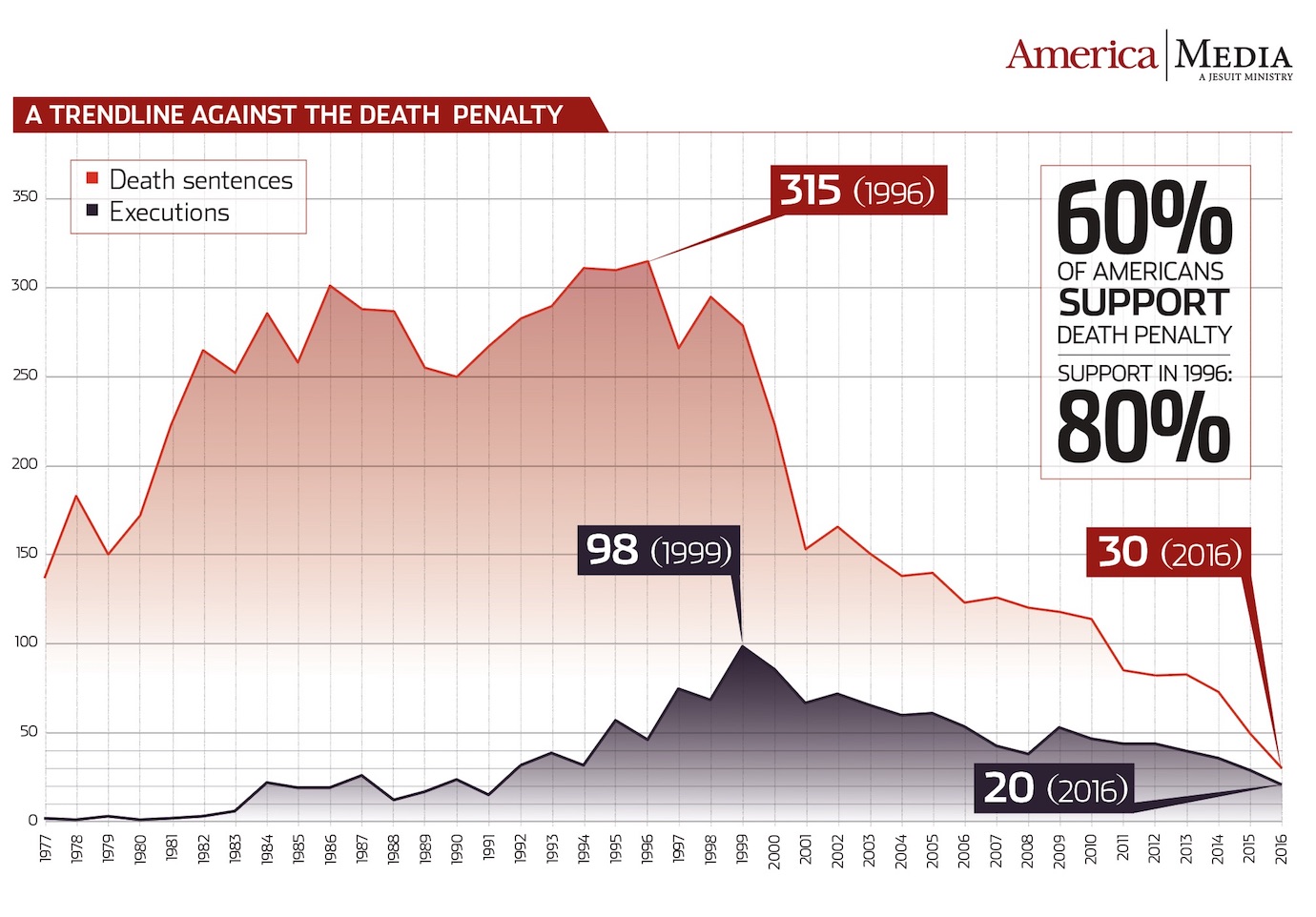

Opponents of the death penalty got some good news at the end of 2016. A year-end analysis from the Death Penalty Information Center finds that the use of the death penalty fell to historic lows across the United States with 20 inmates executed in 2016. That is the lowest number of executions since 1991, when 14 inmates were executed.

According to D.P.I.C.: “States imposed the fewest death sentences…since states began re-enacting death penalty statutes in 1973.” It adds, “New death sentences are predicted to be down 39 percent from 2015’s 40-year low. Executions declined more than 25 percent to their lowest level in 25 years, and public opinion polls also measured support for capital punishment at a four-decade low.” In every other year since 1992, at least 28 people have been executed in the United States.

Diann Rust-Tierney, executive director of the National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty, said the numbers reported by D.P.I.C. were “consistent with what we’ve been seeing—steady momentum away from the death penalty, an increasing number of people opposing it and a declining number who are expressing support for it.”

She added, “We are moving in the direction of the rest of the world” on the death penalty.

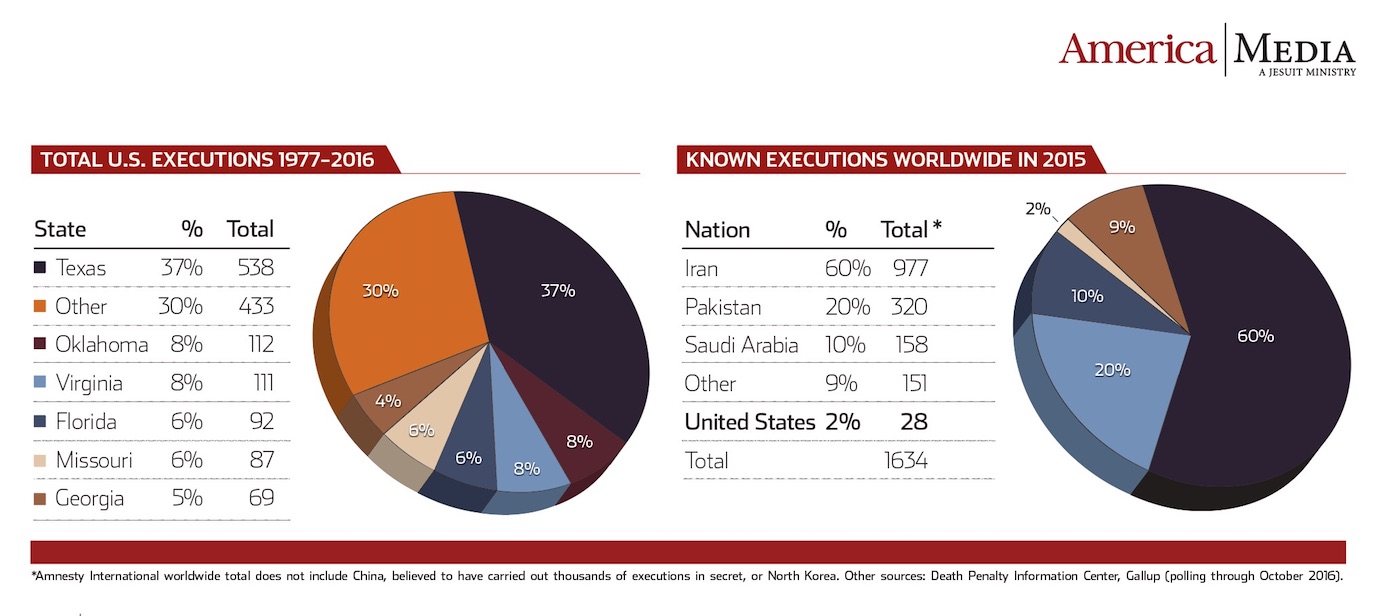

The United States is one of 58 nations, China, Pakistan, Iran,India and Saudi Arabia among them, that have not abolished or otherwise declined to make use of capital punishment. Ms. Rust-Tierney believes the public sentiment away from the death penalty in the United States reflects a growing appreciation that “we don’t need it and the troubles it creates.”

Karen Clifton, executive director of the Catholic Mobilizing Network to End the Death Penalty, commented on the reduced number of executions in 2016 via email. “This is a clear sign that the death penalty is coming to an end,” she said.

“This trend is thanks in part to the continued efforts of Catholics across the country who advocate for the dignity of all life. Through education and prayer, Catholics throughout the country have served a great role in our work to bring about an end to the use of the death penalty and promote a more restorative criminal justice system.”

According to the Pew Research Center, just five states—Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Missouri and Texas—accounted for all U.S. executions in 2016. That represents the fewest states to carry out executions in any year since 1983.

One major reason for the overall national decline was a decrease in Texas, which executed seven inmates this year, a 20-year low, Pew reports. A declining homicide rate in recent years may have contributed to the reduction in capital sentences in Texas, but the state's highest criminal court also sent multiple cases back to trial courts in 2016 because of faulty evidence.

The D.P.I.C. reports that the 2016 numbers nationally depict “the geographic isolation of the death penalty and its disproportionate overuse by a handful of jurisdictions.” The number of state and federal jurisdictions imposing death sentences fell by more than half—“from 60 counties and the federal government in 2012, to only 27 counties this year.”

The report adds, “More than 60 percent of those sentences came from a 2 percent segment of U.S. counties that [have] historically produced more than half of all death sentences.” That hyper-concentration begins to feel a lot like the “capricious and arbitrary” problem that led the Supreme Court to strike down the death penalty in 1972’s Furman v. Georgia decision.

But 2016 was not without setbacks for opponents of the death penalty. November referendums in a handful of states approved or restored the use of the death penalty, while a proposal to end the use of the death penalty in California was turned back by voters. Those same voters approved another measure to expedite capital punishment in the Golden State.

Ms. Rust-Tierney was not concerned that these scattered losses represented a significant shift in public sentiment.

“There is a distinction between momentum and inertia,” Ms. Rust-Tierney said, “and in my mind those [referendum results] represent the work we still have to do.” She attributes the losses to the “difficulty of addressing this complicated, historically entrenched issue in the shortened, frenetic environment of a ballot issue.”

She anticipates that a “two steps forward, one step back” progression may continue in the debate over capital punishment, but she said the momentum against the death penalty was clear, recalling Martin Luther King Jr.’s observation that “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.” Ms. Rust-Tierney remains confident that given the proper factual preparation and time to consider the matter from all sides, most members of the U.S. public will decide against capital punishment.

She assigns a lot of the credit for the public turn against capital punishment to the organizing and moral mettle of the U.S. Catholic Church, which has taken a more prominent role in efforts to abolish the death penalty.

“The energy that is in the Catholic Church [against the death penalty] is really important to our efforts,” she said.

While she is happy to make a practical cost-benefit social and economic case against capital punishment, Ms. Rust-Tierney believes it is the moral arguments made by figures such as Pope Francis that “should carry the day.”

She explains, “We are not just about changing the law; we are about changing the hearts and the minds of the public to a new and better way of relating to each other.”

While the numbers were dramatically down, “unfortunately, the 20 executions that took place demonstrate some of the problems with our criminal justice system,” Ms. Clifton said. “This year’s executions were geographically isolated, and many of the executed prisoners had serious mental illnesses or did not receive adequate representation or court review.”

According to Ms. Clifton, at least 12 of the 20 people executed and 11 of those sentenced to death had evidence of serious mental health problems. She points out that the U.S. Supreme Court has banned the execution of juveniles and people with intellectual disabilities because they have a reduced understanding of the consequences of their actions, “yet those affected by severe mental illness can still be executed.”

Looking ahead to 2017, Ms. Clifton said that the Catholic Mobilizing Network will focus on pressing for the prohibition of the execution of people with mental illness.