El sueño americano. The American dream. Terrifying, promising and elusive, it pulls us from our native lands. We leave behind families and careers; many of us leave to survive, escaping countries shrouded in violence and death. This dream tells us that no matter our circumstances elsewhere, in America we can make it. In America, the land of opportunity and democracy, anything is possible. El sueño americano.It is this dream that is at the center of the 2007 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao.

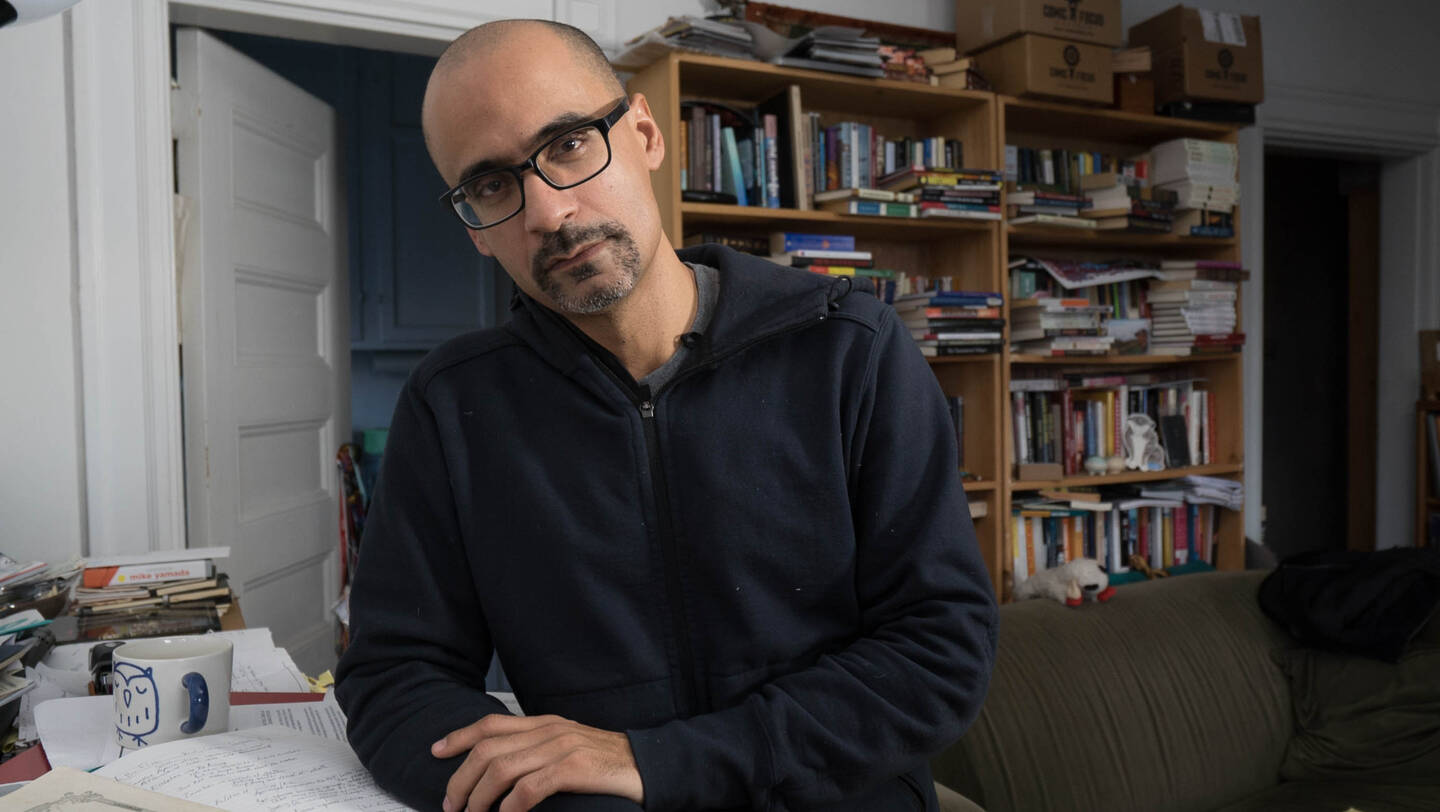

It is a cold Monday afternoon in early January, and I am in Cambridge, Mass., to discuss the novel, which turns 10 this September, with its author, Junot Díaz. As immigrant children, I begin, we learn at a very young age to view America as a kind of utopia, a place to be lauded. Díaz nods in agreement, settling into the chair across from where I am seated.

“From the moment I could remember, it was made very clear to me that I was going to the United States,” he says. “There was already the shadow of the United States over all of our lives. There was a sense that the world that we were inhabiting, the people that we were connected to, the neighborhood that was more or less my entire universe, that all of these things would soon vanish.”

Born in 1968, Díaz spent the first six years of his life in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. “La Capital” is one of the oldest cities in the Caribbean and home to over three million people. The country shares its home—and complicated history—on Hispaniola with Haiti. Christopher Columbus landed in Santo Domingo in 1492, making it the first city to come under Spanish rule. During this time, the country was populated by Taino Indians. Under Spanish rule, men were used as cheap labor, women were raped, and lands and resources were pillaged. The effects of Spanish colonization were so severe that by 1548 the Taino population had dropped from over 1 million to just 500.

As a result, the Spanish began importing African slaves to the Dominican Republic. The introduction of a new culture directly affected the country, especially its religious practices. Over 90 percent of the country identifies as Christian, half as Roman Catholic. It is not, however, the Roman Catholicism found in the United States or Europe. “In the Dominican Republic, it was very hard to escape the sort of syncretic, Africanized Catholic faiths, plural, that are to be found across the island,” Díaz tells me.

Describing this faith in Oscar Wao, the author writes, “We postmodern plátanos tend to dismiss the Catholic devotion of our viejas as atavistic, an embarrassing throwback to the olden days, but it’s exactly at these moments, when all hope has vanished, when the end draws near, that prayer has dominion.” The Christian faith of our viejas, our mothers and grandmothers, is one shrouded in folklore. “I think that a lot of what I was raised to think of as Dominican was inflected by both religious and supernatural complexes,” Díaz tells me.

For the young Díaz, leaving this culture was not easy. “I grew up in this barrio where there’s a ton of kids, where all we did was play all damn day. My experience in the Dominican Republic in those years was living in this wonderland,” he says. Six years later, he and his family left for the United States, joining his father in Paterson, N.J. The transition was difficult. “I immigrated to central New Jersey. I immigrated to an area where there weren’t a lot of Dominicans,” he tells me. “I was not a huge fan of the American experience for my first few years. It wasn’t until I discovered books that I began to feel any fondness toward this adventure that I was on, this adventure called immigration.”

His readers see Díaz’s love of books in what he describes to me as “Oscar’s nerdology” in Oscar Wao. In the author’s home in Cambridge, this fondness is more than apparent. There are books everywhere: stacked by the door, on coffee tables, window sills, mantels and on various piles throughout the apartment he shares with his partner Marjorie Liu, the New York Times best-selling author and comic book writer.

He speaks a dialect I know, one born in the streets of Paterson, the Bronx, Washington Heights, a language born out of our diaspora.

Reading Díaz’s books was the first time I saw myself reflected in literature. Like Díaz, I was born in Santo Domingo, where I would remain for three years before my parents would fly me out to New York City in the winter of 1992. He speaks a dialect I know, one born in the streets of Paterson, the Bronx, Washington Heights, a language born out of our diaspora. It is the language we learn, fluently, in the various American pockets we fill when we leave the Island—a mix of English and Spanish, that eclectic mix of “dimelo!” and “what’s good.” It is the bridge between our motherland and this land, a blending of two countries.

It is this language Díaz perfects in his literature.

Junot Diaz’s first book was Drown. Published in 1996, it is a collection of 10 short stories that first introduced his readers to Yunior de Las Casas. The stories are narrated through the perspective of an adult Yunior, touching on themes related to patriarchal abandonment, homosexuality, immigrant poverty and migration from the Dominican Republic for the United States. The idea for the collection began when Díaz was studying for his M.F.A. at Cornell University. “I was really interested in this idea of telling a story that’s a linked group of stories about, basically, how a certain kind of Dominican male subjectivity is formed,” Díaz tells me. “I conceived of this family, this narrator, who was simultaneously brilliant and profoundly stupid around women and around intimacy. And once I had Yunior as a concept, as a strategy, the book began to come together.” I tell him that Drown was the first time I read his work and saw Dominican characters reflected in American literature. “It is a typical coming of age story, from the point of view of our community’s craziness,” he tells me.

Writing for The New York Times the year of Drown’s publication, David Gates compared Díaz to Raymond Carver, one of America’s finest short story writers. Like Carver, Díaz “transfigures disorder and disorientation with a rigorous sense of form,” Gates wrote. In “How to Date a Browngirl, Blackgirl, Whitegirl, or Halfie,” Diaz presents a story written like a how-to manual. The protagonist, listing a variety of ways to “date a browngirl, blackgirl, whitegirl, or halfie,” says, “Clear the government cheese from the refrigerator”; “Shower, comb, dress”; “Get up from the couch and check the parking lot.” Díaz’s prose is methodical, efficient and beautiful. In one of the most poignant lines in this story—and arguably all of Drown—Díaz commands, “Run a hand through your hair like the whiteboys do even though the only thing that runs easily through your hair is Africa.”

Writing was not the author’s first career choice. He attended Rutgers University in New Jersey in the early 1990s, and, unlike many of his peers, he had no career path. “I didn't know what in the world I wanted to be. I loved books to death, I loved history to death. What was I gonna do with that?” At Rutgers, he found himself immersed in the works of Gloria Naylor, Alice Walker, Gloria Anzaldúa and Toni Morrison. “I came of age surrounded in college by these brilliant women of color and their radical epistemologies.” Díaz would later name several of these writers as influences. By his junior year, his focus on writing grew,and every night Díaz spent at least two hours writing. “I was able to do that for a couple of years,” he tells me, “it proved to me that there was more to this dream than just kind of a desire. There was something beneath it.” Ten years after the publication of Drown, Díaz would introduce readers to what some have called the greatest novel of the 21st century.

“How long did it take you to write Oscar Wao?” I ask. Díaz groans and laughs. “I’m a terribly slow writer. It took about 11 years from those early beginnings to finally getting the last chapter written.”

The first inklings for the book began in 1996. Growing up, Díaz, like most Dominicans, knew of Rafael Leónidas Trujillo Molina. Known as “El Jefe” or The Boss, Trujillo ruled over the Dominican Republic from 1930 until his assassination in 1961. Thirty-one years of the Trujillato, Trujillo Era, left over 50,000 people killed, including over 10,000 Haitians in the Parsley Massacre. “I had a father who was in the post-Trujillo military apparatus, a father who grew up inside of the Trujillato, and was very supportive of it,” Diaz says. “My father had a very romantic vision of who Trujillo was. I did not.”

Díaz’s obsession with the dictator was one of the themes he wanted to include in the novel, along with the “nerdology” of the protagonist, Oscar De León. “As I wrote the book, I began to shape both of these projects. They did not emerge fully formed in my head. I didn’t have the idea of what was joining these two narrative strands.”

In Oscar Wao we are presented with Oscar, an overweight Dominican boy living in Paterson. He is obsessed with science fiction, falling in love and “getting laid” and the fukú, the curse that has plagued the De León family for generations. The story is told through a seemingly ambiguous narrator we eventually realize is Drown’s Yunior. Touching on depression, womanhood, death and violence among other issues, Díaz presents three stories of the De León family. We encounter characters who must deal with what it means to be Dominican in a new country, struggling to live out el sueño americano.

Díaz captures the tension felt by many immigrants. It is difficult to form one’s identity between two countries, two cultures. This tension is present in Oscar. He does not show the qualities he has been told are those of the archetypal Dominican man. He is a virgin who doesn’t want to be one, a voracious reader immersed in the worlds of J. R. R. Tolkien and Oscar Wilde. He wants to fit in, whether with the students at his college or with the people he meets when he visits the Dominican Republic. In one of Oscar’s most distressing moments, Díaz writes, “The kids of color, upon hearing him speak and seeing him move his body, shook their heads. You’re not Dominican. And he said, over and over again, But I am. Soy dominicano. Dominicano soy.”

Then there is Beli, Oscar’s mother, who grew up in the Dominican Republic while Trujillo was in power. Her father is sent to prison by the government, and her mother commits suicide. She is then shuffled from one distant relative to another, until she is finally sold as a child slave. One day, while she's attempting to go to school, Beli’s “father” drops hot oil onto her back.

Beli is scarred, emotionally and physically. She is eventually found by her aunt, known as La Inca, who dedicates her life to helping Beli make the most of her post-trauma life. But Beli’s struggles do not end there. As a teenager, she falls in love with and has an affair with a married man, whose wife is Trujillo’s sister. As a result, she is kidnapped and tortured, “beat...like she was a slave. Like she was a dog.” It is in this character that we see the grisly legacy of the Trujillato. While the story of this family is fictional, the effects of Trujillo’s dictatorship are not. “I wanted to understand and capture this phenomena, the political, social, cultural phenomena that was Trujillo,” Díaz says.

Oscar Wao also features the juxtaposition of two seemingly different cultures: the Caribbean and science fiction. Reviewing the novel for The New York Times, A. O. Scott wrote that Oscar Wao is immersed in “magic realism, punk-rock feminism, hip-hop machismo, post-modern pyrotechnics.” I tell Díaz I am surprised at how well he connected these two worlds. He tells me that the connection is more discernible than it may seem at first. “To read science fiction and fantasy is to encounter within it resonances and echoes of the history of the New World, of Dominicans specifically,” Díaz says. “Science fiction and fantasy stories are obsessed with these questions of power. They’re obsessed with racism. They’re saturated with the political unconscious, with the dark energy of colonialism. And it was only when I was writing the book that I became aware of their affinities.”

To read science fiction and fantasy is to encounter within it resonances and echoes of the history of the New World, of Dominicans specifically.

In 2008 Oscar Wao was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in Fiction. Díaz humbly shrugs when I bring up this honor and instead emphasizes that he is grateful for the spaces it has created for communities of color, particularly Dominicans. “I’m glad it’s opened spaces for the Dominican community at a literary level. I am constantly humbled and gratified that this book continues to speak to anyone.”

My parents arrived from the Dominican Republic in New York City in the winter of 1991. For that first journey here, they left me behind for a year while they settled in America; the island, however, they left behind, essentially, forever. They left a world that made them happy and comfortable, por el sueño americano, they have told me repeatedly throughout my life. Like immigrants before and after them, they struggled. It wasn’t until years later that I would learn how difficult it truly was. They arrived with just $90 in their pockets; the uncle on my mother’s side who promised to pick them up at John F. Kennedy International Airport was nowhere to be found for almost two weeks; and they had no steady jobs or home for months. It wasn’t until years later that I would see these experiences represented in literature, in Díaz’s work. And at a time when our political leaders employ harsh anti-immigrant language, reading experiences like the ones described in Oscar Wao takes on even more importance.

During a Senate floor debate on immigration reform in 2006, Republican Senator Jeff Sessions said, “Fundamentally, almost no one comingfrom the Dominican Republic to the United States is coming here because they have a provable skill that would benefit us and that would indicate their likely success in our society.” Eleven years later, Sessions is now the U.S. attorney general, and this attitude, fueled by the blistering rhetoric of President Trump, has made immigrants something like the national bogeyman.

I bring this up in my conversation with Diaz. I mention the fear among immigrant communities, people of color, women. “This election has revealed this country in ways that little has,” he says. “And for me, Trump is not even the worst of it—the worst of it is the culture that could make Trump possible. We just live in a society that is so addicted to xenophobia, to blind bias.”

So does this change the role of the writer, I ask. Díaz tells me that the role of the writer is the same it has always been, to continue pushing boundaries. “As artists, we’re not here to comfort anyone. If you want to have your back rubbed, you don’t come to the arts for that,” he says. “We’re as artists here to point out the things that we don’t like to point out. We’re the anti-politicans,” he proclaims, “We’re actually trying to make the country better.”

I taught in a NYC public school around the corner from the tenement in which I grew up and in which I still lived when I began my teaching career. The neighborhood and the tenement had already begun to be inhabited by Dominican immigrants to the United States long before I had started teaching.

Many of the children whom I taught were undocumented, as were their parents. My experiences of 25 years teaching in that school, however, revealed a culture and people with a dynamism, an exuberance, and a joy for life and for other people and for NYC and the United States.

I have always referred to Dominicans as the immigrant wave closest to the Irish in the immigrant experience. Dirt poor in most instances, willing to do work that native-born citizens refused, they made an economic and cultural mark on the neighborhoods which they inhabited, all of northern Manhattan, large sections of the west Bronx extending to the edges of Riverdale, and in other boroughs of the city, ironically some of the same neighborhoods of Irish immigration.

Too many of the children whom I taught fell victim to the vices and poisons of the city. That too is part of the immigrant experience in the USA. (There is some poetic justice however in realizing that the same drug dependence now befalls the children of many of those citizens who so roundly support the removal of the undocumented.)

Most of the children whom I taught were thoroughly “Americanized” by this USA culture which is overwhelming and unstoppable. Yet they retained qualities of warmth, joy, exuberance, and openness to others that too many previous immigrant groups never had or have forsaken.

Unlike Sessions, the Attorney General of the United States, Dominicans bring to the nation, to the American dream, something that he and his ilk never possessed, decency, hospitality, and humanity towards any and all whom they encounter. Not a bad contribution to USA!