When future generations look back on the career of Anthony Burgess (1917-93), they may well decide that his many earthly attainments—as novelist, critic, broadcaster, linguist, composer, educator, social provocateur and sometime morale problem to the British Army—pale into insignificance next to a far more important legacy: Burgess’s contribution to the debate about man’s proper relationship to his Creator and especially his own troubled but enduring connection to the Catholic Church.

The church obsessed him. I know this because Burgess himself (who once remarked of his church-going neighbors, “I want to be one of them, but wanting is not enough”) both denied this and proceeded to talk about little else when I met him in 1987, while he was visiting London from his tax exile in Monaco to promote his autobiography Little Wilson and Big God.

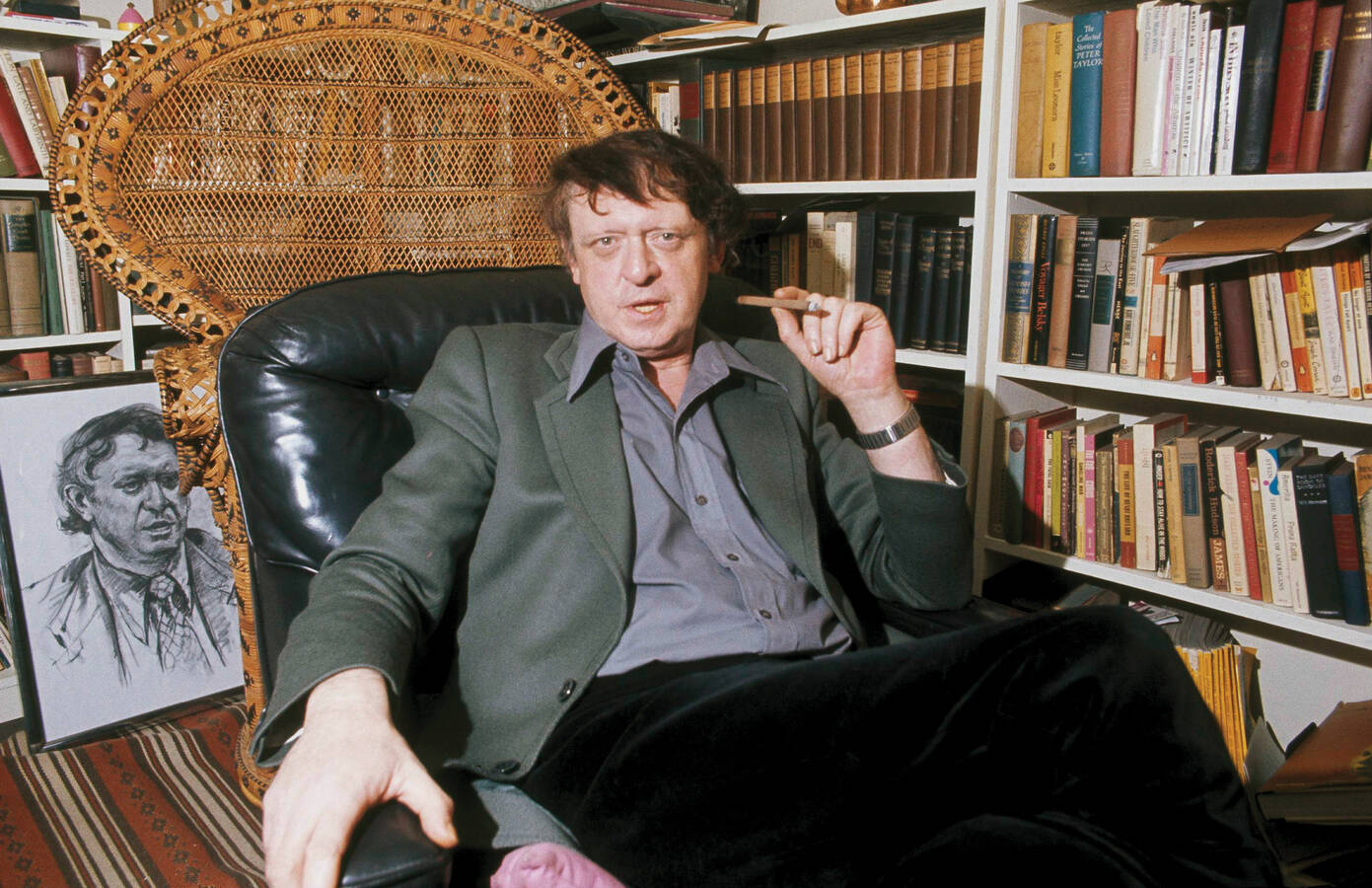

Burgess, perhaps still best known for his dystopian novel A Clockwork Orange, had a Chestertonian love of paradoxical aphorism: “Only when things are pulled apart may they be connected” is one I recall. Or: “Music may best be judged by the resonance of its silence.” Add Burgess’s mad-scientist demeanor, the twin headlamps of his eyes bulging out from the shock of snowy hair, and the amount of booze he put away during our hour together, and you can see why hardened Fleet Street journalists spoke in awe of his frequent mood swings and occasional tantrums. For all his harrumphing admonishments, however, I have to say he was kindness itself during our time together—effusively signing my copy of his 1982 fantasy, The End of the World News.

Though ‘lapsed,’ Anthony Burgess was obsessed with the church.

Burgess was raised as a Roman Catholic in the austere world of post-World War I northern England. He described his background as lower middle class and “of such character as to make me question my worth to God, and his to me, from an early age.” Burgess’s mother, Elizabeth, died when he was only a year old, a victim of the global flu pandemic, just four days after the death of his 8-year-old sister, Muriel. Burgess believed that he was resented by his father, Joseph, a shopkeeper and pub pianist, for having survived. “I was either distractedly persecuted or ignored,” he wrote of his childhood.

He attended local Catholic schools and went on to read English at the University of Manchester. He graduated in 1940 with a second-class degree, his tutor having written of one of his papers, “Bright ideas insufficient to conceal lack of knowledge.”

“As an English schoolboy, I came to reject a good deal of Roman Catholicism, but instinct, emotion, loyalty, fear, tugged away.”

A watershed occurred in Burgess’s already chaotic adolescence when, at the age of 16, he read James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. In fact, he told me, it was one of the three “emotional rips” of his early years. (The other two involved young women.) Joyce’s Künstlerroman proved to be the defining moment of a life Burgess himself never grew tired of laying bare, even if the psychological striptease was performed with more insight and aplomb than that of the average celebrity narcissist.

Writing of this period in 1965, Burgess recalled his discussions with the Jesuit priests at the Church of the Holy Name near his home in Manchester. “With me,” he wrote, “at an age when I could not counter the arguments of the Jesuits, [life] was unavoidable agony since it was all happening, it seemed, against my will. As an English schoolboy brought up on the history of the Reformation, I came to reject a good deal of Roman Catholicism, but instinct, emotion, loyalty, fear, tugged away.”

A ‘Lapsed’ Catholic Obsessed With the Church

Endless problems arose when Burgess began his wartime service in the British Army, a period that further fueled his lifelong sense of being utterly different from everyone else. Of his three-year posting to the British Mediterranean outpost of Gibraltar, he wrote: “I was not quite an agent of colonialism, since I was a soldier. I was not quite one of the colonised, since I was English. But, being a Catholic, I had a place in the Corpus Christi processions of the Gibraltarians. I was part of the colony, and yet I would always be outside it. But I could resolve my elements of new and different exile in my art.”

After a belief in his own cleverness, this sense of being aloof or apart was Burgess’s central conviction about himself and a lifelong theme. He was always looking for it—whether as an “unreconstructed High Tory” in 1960s Swinging London or as a “robust English patriot” who chose to live the last half of his life in exile. Burgess’s idea of a good holiday was to sit on the sun-kissed grounds of a Tuscan villa writing fondly of Manchester in the winter. “I am a contrarian,” he admitted.

Nowhere was Burgess’s impressive ability to annoy both ends of the spectrum on a particular subject better demonstrated than in his religion. Although he proudly identified himself as an “unbeliever” from the age of 16, he continually returned to spiritual themes, whether in his novels, his poems or his screenwriting of the acclaimed 1977 miniseries “Jesus of Nazareth.” Burgess told me in 1987 that this aspect of his life was “an endlessly scratched itch.” Not that he ever for a moment identified with other prominent Roman Catholic authors of his generation (again shunning the lure of the club), telling The Paris Review in 1973 that he felt himself to be “quite alone...the novels I’ve written are really medieval Catholic in their thinking, and people don’t want that today.”

Unlike him, Burgess continued, even the greatest of English Catholic writers “tend to be bemused by the Church’s glamour, and even look for more glamour than is actually there—like [Evelyn] Waugh, dreaming of an old English Catholic aristocracy, or [Graham] Greene, fascinated by sin in a very cold-blooded way.... I try to forget that Greene is a Catholic when I read him. Crouchback’s Catholicism weakens [Waugh’s] Sword of Honour in the sense that it sentimentalises the book. We need something that lies beneath religion.”

About 50 years ago, the British comedian Peter Cook performed a sketch about the doggedly reclusive Greta Garbo in which, adorned by a blonde wig, he stood up in the back of an open-topped car shouting “I vant to be alone!” through a megaphone. Burgess gave the same impression of wanting it both ways when he insisted that he was not the least bit obsessed with the subject of religion.

“I am very far from consumed by curiosity about man’s proper relation to his Maker, let alone the eschatological sanctions of the Roman Church,” he told me when we met, in language that perhaps suggests the opposite was true. In February 1967, when he turned 50, Burgess felt moved to write a syndicated essay that he titled “On Being a Lapsed Catholic.”

It was almost as though annoying his fellow Catholics was a solemn Christian duty.

It was not that Burgess had become any less worthy, charitable or compassionate, he insisted in his essay, after ceasing to believe. Far from it. “The desire to be good...has attained a sharp relish through being more an end in itself,” he wrote. “I have sinned against the Commandments of the Church, but so has the greater part of mankind.” It was almost as though annoying his fellow Catholics was a solemn Christian duty. After condemning the church for its intransigence and vowing never to return, Burgess then rebuked the church for the loosening of its traditional moral guardrails in the 1960s.

“Indeed, I tend to be puristic about [this],” Burgess wrote, “even uneasy about what I consider to be dangerous tendencies to slackness, cheapness, ecumenical dilutions. My cousin is an archbishop; when I went to his enthronement I was appalled at the pedestrian nature of the English liturgy, the demotic sickliness of ‘Soul of My Saviour’, which I had thought the Church to have long discarded as a shameful bit of cheap sugar, and the general weakening of the nobility of the Mass—once either gorgeously baroque or monastically austere.”

The fact that he had once called on the Catholic Church to become more “relevant,” Burgess seemed to be saying, was no reason to assume he actually wanted it to happen. As he once wrote, “I’m a Jacobite, meaning that I’m traditionally Catholic, support the Stuart monarchy and want to see it restored, and distrust imposed change even when it seems to be for the better.” Asked about his religious views later in life, Burgess said: “I don’t think the kingdom of heaven is a real location. I think it is a state of being in which one has become aware of the nature of choice, and one is choosing the good because one knows what good is.”

Characteristically, Burgess added, “If it was suddenly revealed to me that the eschatology of my childhood was true, that there actually was a hell and a heaven, I wouldn’t be surprised.”

‘I Will Opine on Almost Anything’

Something of this same casuistry can be seen in the pages of Burgess’s published canon, most famously his panoramic novel Earthly Powers. The book’s decidedly unreliable narrator, 81-year-old Kenneth Toomey (the Burgess alter ego) is essentially agnostic, in contrast to his friend Carlo Campanati, who sees life as part of a cosmic jest of unfathomable cruelty and who goes on to be elected pope. “A saint,” Campanati says, “has to modify the world in the direction of being more aware of the presence of God in it.” An author, Toomey’s priorities are different: “I can’t accept that a work of fiction should be either immoral or moral. It should merely show the world as it is and have no moral basis.”

Some critics saw Earthly Powers as a profound rumination on good and evil and, more particularly, a satirical tour d’horizon of everything from the Nazis to gay marriage as seen through the eyes of Campanati, the dates of whose papal election and death correspond to those of Pope John XXIII. Might it be, however, that the book is less of a scholarly meditation on sin per se and more an occasion for Burgess to indulge in the sort of verbal fireworks he did better than any other contemporary writer?

When I politely asked him about this, he exhaled a great cloud of cigarillo smoke and laughed at the question. “My dear boy,” he said at length, “I will opine on almost anything to pay the bills.” Indeed, I found that in the years immediately before publishing Earthly Powers, Burgess had gone into print with a Time-Life guide to New York City, a verse novel about Moses and a book review that dwelt at length on the minutiae of car maintenance in winter. “It is all one to me,” he announced. There was no particular merit to writing about the papacy as opposed to “discussing the optimum brand of antifreeze for the family Ford.”

That, I think, was Burgess all over. He wanted it both ways and every way—the lapsed Catholic who, like one of his characters in 1962’s The Wanting Seed, takes “a sort of gloomy pleasure in observing the depths to which human behavior can sink” and the overgrown schoolboy who reveled in his own powers of invention, which frequently veered toward the parodical or even cartoonish, and for whom the great questions about man’s purpose on earth were merely another occasion for the pyrotechnic display of his fabulous literary gifts.

“I confess that I want pagan night—una nox dormienda,” Burgess wrote in 1967 in On Being a Lapsed Catholic. “Not solely, however, because nothingness is better than the prospect of pain, even terminable pain. It is more because I want Anthony Burgess blotted out as a flaw in the universe.”

It is another paradox about a man who professed to be totally indifferent to his birthright religion and yet rarely avoided an opportunity to expound on it that he clearly saw himself as anything but a mere “flaw” in God’s plan.

The impression I got of Burgess was one of enormous jollity and zest for life. He may have been from time to time exhausting to listen to—certainly he can be exhausting to read—but for anyone interested in exploring the heady mixture of a wonderfully good spy story couched in a metaphysical debate about God’s creation, I recommend Burgess’s 1966 novel Tremor of Intent. It comes as close as possible to giving us the essence of the man himself in all his coarse, humorous, restless, tragic glory.

Yawn

The whole of life is a pilgrimage. It is a tapestry because our sins of pride always tangle with our wisdom.

A. B.: a vastly lesser Joyce.