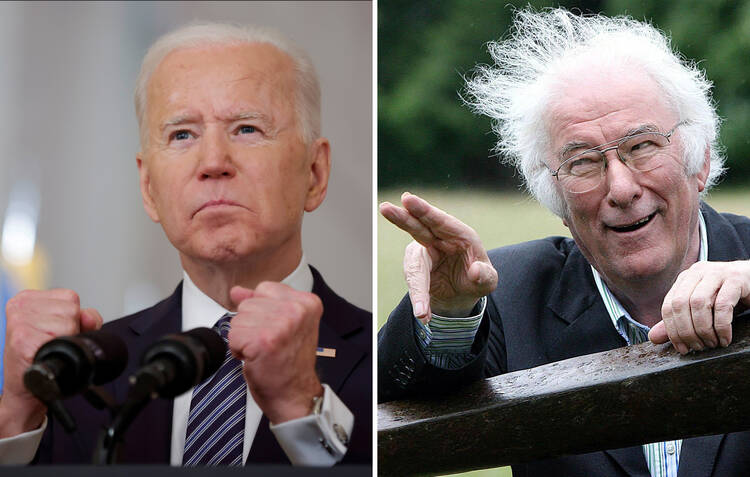

Upon the occasion of his acceptance of the Democratic nomination for president on Aug. 20, President Joe Biden quoted a poet’s words with which we are all now familiar: “The Irish poet Seamus Heaney once wrote: ‘History says/ Don’t hope on this side of the grave/ But then, once in a lifetime/ The longed-for tidal wave/ Of justice can rise up/ And hope and history rhyme.’”

In many ways, these words have charted the highs and lows of President Biden’s recent career. He used them as far back as his failed presidential campaign in 2008, and he paraphrased them on the evening of his inauguration in January. Indeed, Joe Biden has gone to the Heaney well so many times that he has made fun of himself for it. “My colleagues always kid me about quoting Irish poets all the time. They think I do it because I’m Irish,” he told Chinese officials in 2013. “I do it because they’re the best poets.”

In this season of discontent, Heaney’s words have become emblematic of President Biden’s greatest challenge: to act as healer-in-chief.

So why Heaney again now? Heaney’s vision of the moment when “hope and history rhyme” can easily be dismissed as rhetorical window-dressing, the poetry of the campaign trail that inevitably gives way to the pragmatic prose of governance. In this season of discontent in American society, however, Heaney’s words have become emblematic of President Biden’s greatest political challenge: to act as healer-in-chief for a nation traumatized by domestic partisanship and global pandemic.

A Christian Hope?

If Healer-in-Chief Biden proposes his presidency as the moment that “hope and history rhyme” for a damaged American nation, the question arises: what kind of hope? And hope for whom? The post-Trump reset heralded by Biden’s Democratic presidency might well prove historic, but this political key change does not necessarily ring of hope for the 74 million Americans who voted against it in the ballot box. To project his victory as a politically destined “end of history” moment—of the sort envisioned by Francis Fukuyama in his 1992 book The End of History and the Last Man—might appeal to sentimental Democrats, but it would constitute a shallow vision of hope for President Biden.

It would also ignore the true depth of partisan division in the United States and fatally undermine his attempts to lead America into a time of healing. The hope to which Biden appeals with Heaney’s iconic lines needs to be more than hope for political retribution. Addressed to the very “soul” of America, Biden’s vision needs to transcend the political realm and achieve a more profound, spiritual dimension. On closer inspection, the prayerful idiom of Heaney’s words suggests that the spiritual hope on which Biden’s mission as healer-in-chief rests could, in important ways, be a Christian one.

The societal landscape to which Heaney raised his great paean of hope in 1990 was as divided as America is today.

The societal landscape to which Heaney raised his great paean of hope in 1990 was as divided as America is today. Delivered through an adaptation of Sophocles’s ancient Greek tragedy, “Philoctetes,” and addressed delicately in 1990 to an Ireland beset by the wounds of sectarian violence, they are an act of supreme ventriloquism. Over the years, they have become literary shorthand for a societal vision of hope that, in Heaney’s words, chooses “the civic, sober path of adjustment...over the intoxication of defiance.”

As Biden chose Heaney to deliver his message of hope, so Heaney chose Sophocles to deliver his. Heaney decided to translate and adapt the story of “Philoctetes”—with its themes of struggle, suffering, justice and pride—to deliver a message of hope that would resonate across the violent sectarian divides of Northern Ireland in 1990. Philoctetes, bitten by a snake on the way to Troy, is abandoned by his fellow Greeks on a deserted island, only to be called back into service after many years of agony. The Greeks need his magic bow to finally conquer Troy, but in a struggle between integrity and duty, between pride and compromise, the stubborn hope of Philoctetes for revenge on his fellow Greeks threatens to extinguish the possibility of anything greater. In the character of Philoctetes we are confronted, as Heaney himself later put it, by the familiar partisan conviction: “a sense that the pride in the wound is greater than the desire for the cure.”

A Poetic Prayer

In order to produce a hope that would have meaning for every side of this damaged society—“innocent in gaols...the hunger-striker’s father...the police widow”—Heaney addresses ideas of suffering, divinity and love in fundamentally different ways from Sophocles. Heaney’s methods bear the mark of the Christian upbringing that, by his own admission, had “totally shaped” his own life. Heaney’s adapted economy of hope in “The Cure at Troy” is geared toward the “the humdrum and caritas of renewal,” as the poet later put it. Even in the minutiae of translation, Heaney’s project is visible. He has Philoctetes appeal for “pity for those less fortunate than yourself.” It is a version of social justice that is more Samaritan than Sophoclean, and one that does not appear in the Greek of “Philoctetes.”

Heaney’s vision is addressed to the nitty-gritty of daily human life, with its anticipating, its suffering, its hoping for something better.

The extended choral speeches at the beginning and end of the play bear most closely the fingerprints of Heaney’s project. These excerpts do not have equivalents in the Greek original: They are Heaney’s own. At the very beginning of the play, the poet wastes no time in outlining the destruction wrought by those whose desires extend no further than the self.

All throwing shapes, every one of them

Convinced he’s in the right, all of them glad

To repeat themselves and their every last mistake,

No matter what.

Later, in the “hope chorus” from which Biden quotes, Heaney proposes a remedy: an interdependent hope that extends beyond the self. The “tidal wave of justice” (an image Biden has drawn on) envisaged by Heaney carries with it the protagonists on both sides of the Northern Irish divide, including the aforementioned hunger-striker’s son and the police widow. Nothing short of a “great sea-change” in our thinking, we are told, will achieve the sort of interdependence that is constitutive of real hope.

Indeed, with the very final words of his “The Cure at Troy,” Heaney leaves ringing in his audience’s ears the fragile suggestion that love of neighbor—that most Christian of concepts—is the path forward toward the vision of hope he has conjured in his work: “I leave/ Half-ready to believe/ That a crippled trust might walk/ And the half-true rhyme is love.”

Heaney’s vision in the hope chorus addresses itself to the nitty-gritty of daily human life, with its anticipating, its suffering, its hoping for something better. In the Christian tradition, this is the same fragility toward which prayer addresses itself. In his Summa Theologiae, Aquinas describes prayer as “the idiom of hope.” (ST, 2.2ae 17, 4.) It is humanity’s attempt to articulate the great uncertainty of its existence and the content of its desires. It is in this sense that Heaney’s great hope chorus can be understood as a sort of poetic prayer.

Appeal to a Christian God

To what sort of God is Heaney’s prayerful vision of hope addressed? The poet’s work offers a choice between two competing visions. The first vision of hope rests on the interventions of a detached deus ex machina, the unfeeling arbiter of the ancient Greek economy of hope. The Greek gods do not take it upon themselves to care for the humans under their control, but they possess the power and the discretion to intervene arbitrarily to resolve their difficulties. This is what ultimately happens at the end of “Philoctetes,” where Heracles appears to impose an unlikely resolution between Philoctetes and the Greek army by whose hands he has innocently suffered. This resolution seems to “fix” the suffering of Philoctetes by overriding it.

Heaney hints at another, more compassionate hope throughout “The Cure at Troy.” In fact, there have been suggestions that the poet adds a Christian God to the ancient text. Such suggestions are overblown, but Heaney’s work is a useful vantage point from which to assess the content of the Christian virtue of hope. The Christian God is one whom Pope Benedict XVI (quoting Bernard of Clairveaux) calls in his encyclical “Spe Salvi” the deus non incompassibilis: “the god who is not unable to suffer with” his people. As the Christian tradition teaches, the Easter hope offered by Jesus does not claim to minimize or override our suffering, but to transfigure it. “It is not by sidestepping or fleeing from suffering that we are healed, but rather by our capacity for accepting it, maturing through it and finding meaning through union with Christ, who suffered with infinite love,” he adds (“Spe Salvi,” Nos. 36-37).

Heaney was studiously God-shy. Joe Biden is not.

By his suffering, death and resurrection, Jesus gives meaning to our suffering. He gives us his consolation—the promise to be with us in our aloneness: “God cannot suffer, but he can suffer with. Man is worth so much to God that he himself became man in order to suffer with man in an utterly real way—in flesh and blood—as is revealed to us in the account of Jesus’s Passion,” Benedict XVI continues. “Hence in all human suffering we are joined by one who experiences and carries that suffering with us; hence con-solatio is present in all suffering, the consolation of God’s compassionate love—and so the star of hope rises (Nos. 36-37). As such, Christian hope exists by definition in the face of, indeed in the very teeth of the worst of human suffering.

Heaney’s deft adaptation across time was never so explicit as to identify the hope or the divinity of “The Cure at Troy” as overtly Christian. The state of counterpoise in which the art of good adaptation exists means that the deus ex machina of “Philoctetes” was not replaced in “The Cure at Troy” by a Christian deus non incompassibilis. The hope chorus concludes with an opaque suggestion that:

If there’s fire on the mountain

Or lightning and storm

And a god speaks from the sky

That means someone is hearing

The outcry and the birth-cry

Of new life at its term.

Interestingly, when Biden and his team released a slick recitation of the hope chorus on the eve of the election, they engaged in their own Christianizing. Heaney’s “a god” was changed to the more Christian-sounding “God.” This alteration was more literary vandalism than ventriloquism, but it suggests that Biden is keenly aware of the spiritual currency of Heaney’s lines.

Heaney was studiously God-shy. Joe Biden is not. Indeed, Christian prayer is still the idiom of hope that resonates with millions of Americans today. If indeed President Biden intends to take Heaney as the guide for his mission as healer-in-chief of a broken American nation, it is clear which of the two visions of hope in “The Cure at Troy” he must pursue. If he rules as an aloof POTUS ex machina, intervening unfeelingly to impose his resolutions on an ailing nation, these political “fixes” will likely constitute a narrow partisan hope for his own supporters.

If Biden taps into his widely acknowledged capacity for empathy (he claims to keep a running tally of America’s pandemic dead in his breast pocket), he can approach the sort of interdependent hope with which Heaney’s hope chorus sought to transcend the deep societal divides of Northern Ireland in 1990. Perhaps Biden will follow the dubious political tradition of campaigning in poetry only to govern in hard-nosed prose. But if the president wishes to make good on his mission as healer-in-chief and govern in the Christian idiom of his favourite Irish poet, he must be a leader who suffers with his people. He must be a POTUS non incompassibilis.

More from America: