Ernest Hemingway was a terrible person.

He was selfish and egomaniacal, a faithless husband and a treacherous friend. He drank too much, he brawled and bragged too much, he was a thankless son and, at times, a negligent father. He was also a great writer.

This is the argument in a nutshell of “Hemingway,” the new documentary by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick and the most recent installment in the revered PBS “American Masters” series. Over the course of six hours, the three-part series insists that viewers hold in tension this seeming contradiction without trying to resolve it. We are forced to face the troubling fact that the gods of art often use the least worthy among us to be their vessels, and despite the constant barrage of evidence revealing our hero’s awfulness, hour by hour, we are expected to get over it. “Hemingway” raises the provocative question, Is it possible to admire the art produced by a writer whom the reader dislikes, disdains, perhaps even despises? The answer, according to Mr. Burns, is an emphatic Yes.

We are forced to face the troubling fact that the gods of art often use the least worthy among us to be their vessels.

The documentary succeeds admirably in its quest to uphold the value of Hemingway’s work and confirm his literary legacy, even as it mercilessly exposes the author’s weaknesses. By no means is this an easy thing to do. Each of the writers and critics who testify to his greatness as a stylist and a storyteller acknowledges, at some juncture, a breaking point—an episode in Hemingway’s life that is repellent, reprehensible, unfathomable and unforgivable. For Tobias Wolff, it is the sadistically cruel letter Hemingway writes upon reviewing the manuscript of From Here to Eternity, a 1951 novel by newly-discovered young writer James Jones. After a series of vicious comments and brutal criticism of the book (mostly unfounded), Hemingway concludes, “I hope he kills himself”—piercing words that made the hair on the back of my neck stand up, knowing what the future holds for Hemingway. In response to this same letter, in which Hemingway employs some scurrilous racial insults and epithets, the African-American critic Marc Dudley responds to his interlocutor, “I’m not sure what to say about this to explain it away. You can’t explain it away.”

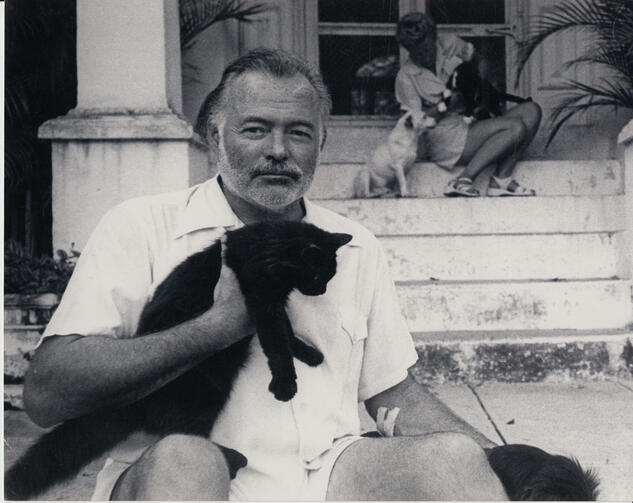

This pattern continues throughout the documentary: praise and admiration for Hemingway’s writing, along with some judicious criticism, followed by painful facts and character flaws that cannot be “explained away.” So much of what Hemingway loved and valued is considered distasteful in our current culture: his admiration for the art of bullfighting, his passion for big game hunting (the photographs of dead lions and now nearly-extinct rhinos—a smiling Ernest posing above their lifeless carcasses—are hard to look at). And yet from his childhood Hemingway was enchanted by the natural world, and as an adult he admired the beauty and power of wild animals, the bravery of the bull. He wrote about them with extraordinary sensitivity and precision. “The pleasure in killing,” Tobias Wolff admits, “is a mystery to me.”

What we as viewers come up against again and again is precisely this—what Flannery O’Connor calls “the mystery of human personality.” Despite six hours of footage, testimony by family members, friends, biographers and scholars, as well as Hemingway’s own admissions of his failings, the man remains an enigma.

One cannot—and should not—pluck out the heart of another human being’s mystery. We know this, and yet Hemingway himself invites the prying eye.

This, of course, should not surprise us. One cannot—and should not—pluck out the heart of another human being’s mystery. We know this, and yet Hemingway himself invites the prying eye, having created a larger-than-life version of himself for public consumption, a mythos meant to identify him with the similarly larger-than-life characters he wrote about. In part two of the series, Wolff states that like a lot of famous people, Hemingway created “an avatar of himself.” The problem is that “eventually your avatar will consume you.” Edna O’Brien counts among Hemingway’s failings the fact that “he loved an audience—and in front of an audience he lost the best part of himself trying to impress them.” Within the mythology Hemingway invented for himself were the seeds of his own destruction.

Hemingway may have been responsible, in ways both figurative and literal, for his own undoing, but there were other factors that shaped his fate. Another theme introduced at the start of the documentary is the dark shadow of mental illness. Young Ernest’s father, who would eventually die by suicide, suffered from sometimes crippling bouts of depression during the boy’s childhood. Sadly, the son inherited his father’s malady. In addition, Hemingway sustained his first concussion at the age of 18 when he was nearly killed by a mortar blast in Italy while serving as an ambulance driver in World War I. When he returned to his placid hometown of Oak Park, Ill., he suffered from PTSD, despite the air of bravado he projected. He confessed to feeling “shot to pieces” and was afraid to sleep in the dark.

He would sustain multiple concussions in the course of his life, surviving several car accidents and two plane crashes. As he aged, these injuries took their toll. He self-medicated with alcohol. His behavior became more and more erratic and abusive towards his wives and friends. Most devastating to him, he eventually lost the ability to do what he loved and did best—write. Toward the end of his life, dogged by depression and suicidal thoughts, he underwent electroshock therapy, a treatment that causes loss of short-term memory. Sitting down to his desk after these treatments, he could not write more than a single sentence in the course of four hours.

As viewers we feel this loss keenly, in part because the documentary does a superb job of reminding us, from start to finish, that what we value in Hemingway first and foremost is his identity as a writer. The first image of the opening scene is the handwritten manuscript of A Farewell to Arms. Seeing the words of that iconic novel’s beautiful opening paragraph in Hemingway’s neat hand makes the heart of any book lover beat faster. This is the stuff—this is the real mystery—the creation of a powerful work of art that tells its story, speaks its truth and stands the test of time. This was the drug Hemingway loved. This is why readers have loved him for nearly a century.

Who knows? Perhaps if Ernest Hemingway were a better man, he’d have been a lesser writer.

Throughout the film, Burns allows Hemingway’s writing to speak for itself. There are long, leisurely readings from his finest stories and novels—“Indian Camp,” “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber,” among others. The clean, incisive language of his fiction is complemented by Hemingway’s often profound words about his own work: “I’m trying in all my stories to get the feeling of the actual life across—not to just depict life or criticize it—but to actually make it alive so that when you’re reading something by me you actually experience the thing.” This desire to incarnate experience in language, to enable the reader to feel the sensation of life on her pulses—to live vicariously through the writing and through the writer, who serves as mediator, conduit and secular priest—is a reflection of Hemingway’s deep hunger for and abiding love of life. This vicarious living is what literature, at its best, does, and Burns doesn’t let us forget that this is the legacy Hemingway leaves us.

Hemingway once stated that he wanted to be a good man as well as a good writer. He also acknowledged he feared he might fail at both. He wrote some great books, books that “remade American literature,” in the words of more than one critic. He also wrote some books that trouble contemporary readers—books wherein he treats women and people of color and people of different ethnicities in unacceptable ways. We wrestle with those books, those images, those words. He also wrote books that he himself recognized as failures. Despite the misfires and the setbacks, he kept on writing and writing and writing, until he could write no more. And then there was no reason to live. The man who could survive mortar shells, car wrecks, and plane crashes could not survive this calamity.

As good as Ken Burns’s film is, there are inevitably weaknesses. Most notably among these, he seems uninterested in Hemingway’s spiritual life. He mentions in passing that Hemingway converted to Catholicism when he married his second wife, Pauline Pfieffer, who was a devout Catholic. But he neglects to mention Hemingway’s own confessions in his letters and commentaries that his conversion actually took place when he received Communion and Last Rites from the hands of a priest in Italy when he was wounded at age 18; that he was a faithful—if very imperfect—Catholic for the remainder of his life, attending Mass and supporting the church; that he raised his three sons in the faith. Burns also fails to mention the fact that a priest presided at Hemingway’s funeral.

This is a regrettable omission, as it leaves out an aspect of Hemingway’s personality and way of being in the world. It would help explain his passion for bullfighting, for instance, which he saw as a kind of liturgy; it also gives us insight into his unwavering commitment to mastering a kind of writing that is analogical in orientation and incarnational in nature. It sheds light on his own trajectory as a sinner in search of redemption working out his salvation in fear and trembling.

Ernest Hemingway may have been a terrible person, but perhaps it was his identity as a sinner that made it possible for him to understand the sinners all around him, to write about them with deep interest, commitment and compassion. Who knows? Perhaps if he were a better man, he’d have been a lesser writer.

More from America: