How can contemporary art help Christians better understand ancient truths? Museums affiliated with three Midwestern Jesuit universities are seeking to provide some answers to that question in a new exhibition currently showing at the Museum of Contemporary Religious Art, or MOCRA, at St. Louis University.

The exhibit, “Double Vision: Art from Jesuit University Collections,” contains 28 works of art curated in a way that mirrors the Stations of the Cross, a traditional way of praying by contemplating the final moments of Jesus’ life. The traditional 14 stations are reimagined with themes such as justice, solidarity and honesty, and two works of art—from MOCRA, the Haggerty Museum of Art at Marquette University and Chicago’s Loyola University Museum of Art—accompany each station.

“We’re taking different works of art and seeing them through all sorts of different lenses,” said Lynne Shumow, the curator for academic engagement at the Haggerty Museum, who came up with the idea for the exhibit. “I’m always trying to make it clear to our students that art is a way of seeing the world and that it’s not just about making things. It’s about understanding all sorts of different cultures and reflecting on history and thinking about contemporary issues.”

How can contemporary art help Christians better understand ancient truths? Museums affiliated with three Midwestern Jesuit universities are seeking to provide some answers to that question.

Ms. Shumow said she was surprised at how little collaboration has existed among museums affiliated with Jesuit colleges and universities. When a faculty member at Marquette suggested that an exhibit inspired by the Stations of the Cross would be a helpful teaching tool, she contacted her colleague at the MOCRA, David Brinker, and the pair began brainstorming about how to draw from multiple collections.

“The aim was to explore the ways that Jesuit university museums in particular can collaborate and discover the ways that our collections are complementary and quite diverse,” Mr. Brinker said. This exhibit, he added, is “intentionally grounded in Ignatian imagination, spirituality and the ethos of an Ignatian education.”

Mr. Brinker said some of the contemporary pieces call to mind more traditional religious works that might immediately be evident to some observers, which he said is a chance to consider the messages of both pieces more deeply.

Two pieces in the exhibit evoke artifacts that are familiar to many Christians: Veronica’s Veil, a piece of cloth said to be used to wipe the face of Jesus; and the Shroud of Turin, a fabric with the imprint of the face of man who has been crucified, which some Christians believe was used to wrap the body of Jesus and depicts his face.

Daniel Goldstein’s “Icarian XI/Leg Extension” is made from a leather cover of an exercise bench from a gym in San Francisco’s Castro neighborhood. Created in the 1990s, when AIDS was hitting the gay community hard, the worn leather resembles a face, which might call to mind the shroud. That is also true for “El Santo Sudario,” an image by the Guatemalan photographer Luis González Palma showing a piece of linen with an image of a Mayan elder wearing a crown of thorns.

“This is not an idealized or generic face of Christ,” Mr. Brinker said. “This is a portrait of an actual person.”

He said the photo “takes us beyond the Gospel story into our present day and the lived realities of other people” and called the experience of viewing the photograph “a challenge to see the face of Christ in the people we encounter.”

In the traditional Stations of the Cross, the second station depicts Jesus being made to bear his cross. The Double Vision exhibit focuses on the theme of courage, with two works that explore trauma and resistance.

Artist Kara Walker’s piece “no world” is taken from her series “An Unpeopled Land in Uncharted Waters,” which, according to the exhibit catalog, “addresses the history of the transatlantic slave trade and its associated violence.” Displayed with Ms. Walker’s piece is “Red Sea” by the Trinidadian-American artist Gary Logan. “Red Sea,” with hues of deep red and bright orange, is meant to evoke reflection on the shared salinity of blood, sweat and the ocean, perhaps calling to mind the 19th-century painting “Slave Ship” while also calling attention to the warming of the oceans.

Many of the stations utilize modern pieces to depict the themes, but a handful rely on a juxtaposition of old and new.

For the ninth station, traditionally showing Jesus falling for the third time, two works are selected to convey wisdom, each depicting women and their role in passing along memory and insight from one generation to another. Jean Bourdichon’s 15th-century oil painting “The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne” shows the two women seated, each holding an open book, suggesting that Anne is teaching Mary how to read.

Opposite that is “Reunion,” a collage created by Romare Bearden in 1974.

Writing in the catalog, art historian Paula Wisotzki describes the piece: “Reunion unites a frail, seated female figure with a robust, standing woman. The younger person leans down to tenderly embrace her elder as they greet one another in the yard outside a humble, weathered home.” Mr. Bearden draws on his own life, growing up in an African American community in rural North Carolina. “Reunion” is one of six collages Mr. Berden created and is meant to evoke, according to Professor Wisotzki, “the wisdom and experience [that] passes from older woman to younger woman, from mother to child, the debt warmly acknowledged by the younger figure.”

The final station, when Jesus is laid in the tomb, is represented in the exhibit by hope.

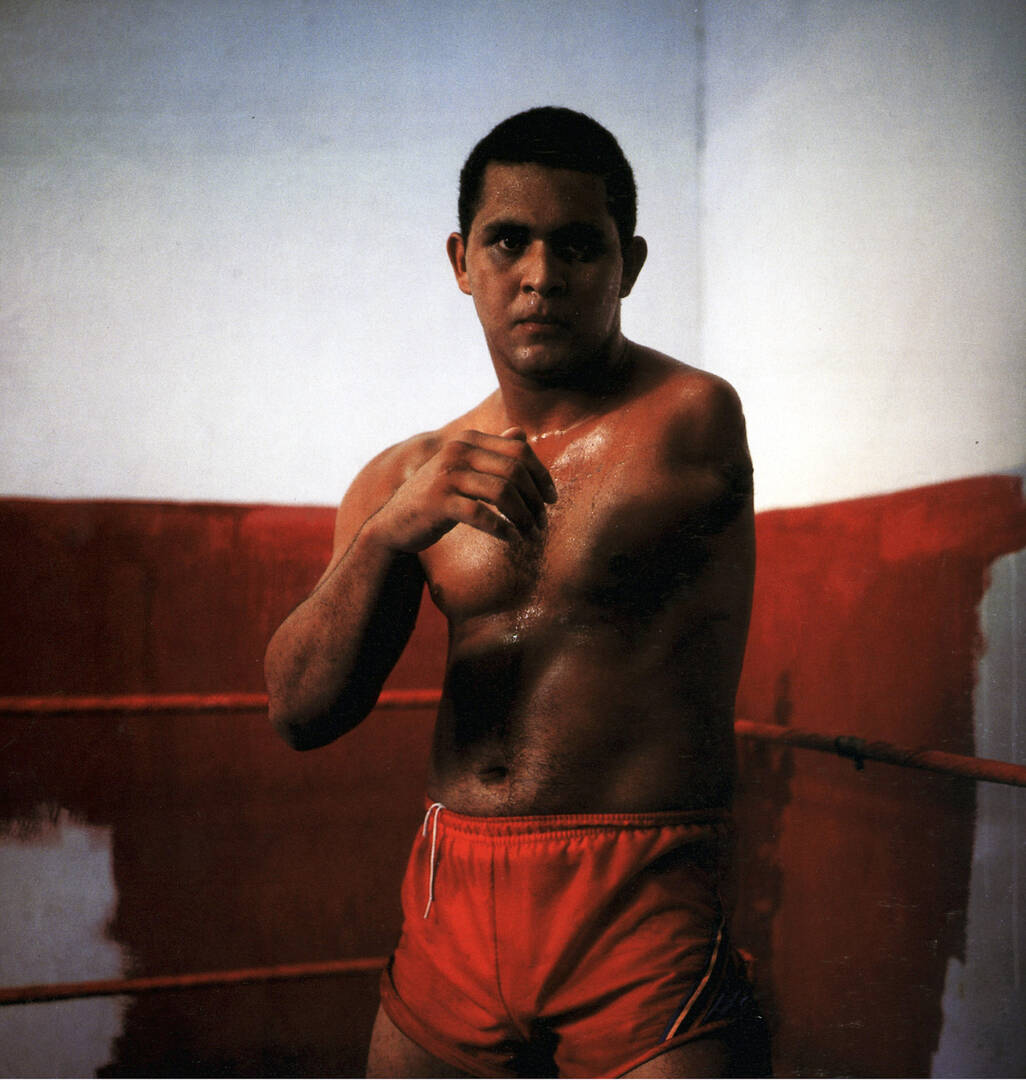

One piece, “The Harrowing of Hell,” by an unknown artist, dates back to the 16th century. It is made of silk threads on linen, showing the gates of Hell opened and Christ pulling a figure up from the flames. Opposite that is a photograph by the Brazilian photographer Miguel Rio Branco, called “Sem.” A description in the catalog, written by Linda Piacentine, an associate professor of nursing at Marquette University, says the photo shows “a one-armed boxer vibrantly alive, in contrast with the lifeless and incompletely painted background. The man appears poised for action.”

Ms. Shumow said visitors to the exhibit are invited to consider how the art speaks to them without being told what it means.

“We gave students a lot of opportunity to look at how we paired these works and draw different conclusions, for themselves, [about] what the meaning may be,” she said.

She recalled one student who had grown up deeply involved in his faith until he came out as gay to his parents. That experience had distanced himself from the institution.

“He long associated Catholic institutions with not being welcoming or not understanding who he was, who he is,” she said. “And coming here and seeing the exhibition...was really a major sort of experience for him. He felt welcome. He felt understood.”

Double Vision ran at the Haggerty Museum last fall and is on display at MOCRA through May 22.