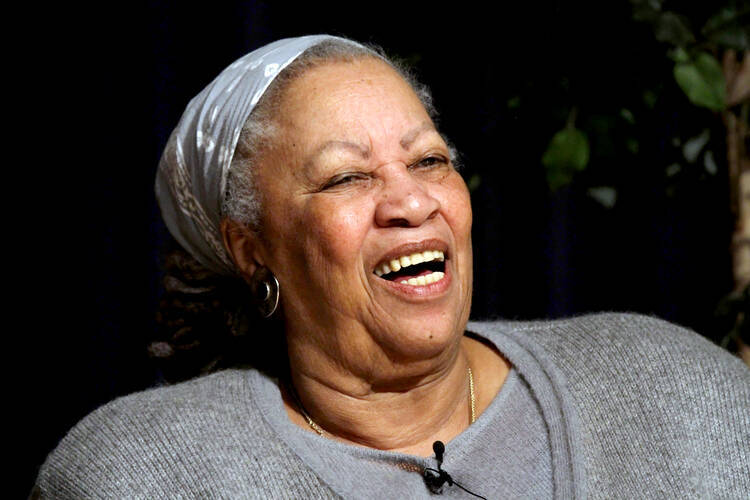

During Banned Books Week 2022 (Sept. 18-24), library employees around the country brought attention to current and historical attempts at censorship and silencing of authors. Joined by many colleagues in publishing and education, they sought to spotlight specific authors and subjects that were targeted in school districts and public libraries around the country by individuals and groups seeking to have books removed from shelves that might be offensive or indoctrinating. One author who will be familiar to many America readers came up numerous times: She has had not one, not two, but three of her books on the “most banned” lists: Toni Morrison.

Both Beloved and The Bluest Eye have been targeted repeatedly in recent years for removal from libraries and schools. The former won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1988. Another of Morrison’s novels, Song of Solomon, won the National Book Critics Circle Award in 1977, but has also been the target of challenges by school boards in three different states.

As Baby Suggs notes in Beloved, “Not a house in the country ain’t packed to its rafters with some dead Negro’s grief.”

In 1993, Morrison was honored with the Nobel Prize in Literature, and in 2012, President Barack Obama gave her the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Morrison died on Aug. 5, 2019, at the age of 88. A memorial service several months later in New York City included eulogies by Angela Davis, Oprah Winfrey, Fran Lebowitz, Ta-Nehisi Coates and Michael Ondaatje.

According to the American Library Association, the most common grounds for challenging books on school reading lists are the depiction of L.G.B.T. lifestyles, sexual material, contentious religious viewpoints, profanity and content that addresses racism and police brutality. In the case of Morrison, the criticism tends to be more vague—because the real issue seems to be that Morrison’s fiction makes white people uncomfortable.

It should. Beloved is a difficult book to read, not because the book is lurid or exploitative or crass, but because it is relentless in its depiction of the horrors white people inflicted on Black people both during and after slavery. The casual and unreflective violence of our culture comes through in almost every interaction. Morrison doesn’t tell watered-down versions of her stories. Rape, incest, pedophilia and physical violence are present in her books because they were and are present in the real lives of people very much like Morrison’s characters. As Baby Suggs notes in Beloved, “Not a house in the country ain’t packed to its rafters with some dead Negro’s grief.”

Boreta Singleton: “Toni Morrison’s characters always find faith in themselves, in God and in the circumstances of life, without always explicitly naming it as faith."

In his book Longing for an Absent God, Nick Ripatrazone examines the role of the Catholic faith in American fiction in the years since the Second Vatican Council. He posits that Morrison (who became a Catholic in her teens—“Toni” is a shortened version of her confirmation name, Anthony) makes strong connections between Black suffering and Christ’s own, especially in Beloved and The Bluest Eye. “Morrison’s theology is one of the Passion: of scarred bodies, public execution, and private penance,” he writes.

Morrison’s characters are resilient and strong, but it is because they are inevitably in a situation where the alternative is death, either of the body or of the soul. Her characters also often thrive in a liminal space between the natural and the supernatural. “A belief in a world other than one in which blacks are dehumanized and devalued helps her characters thrive, as it did for Morrison’s very own family members,” wrote Nadra Little in a 2017 America article. “She remarked during a 1983 interview that her characters are high-functioning—they are able to navigate day-to-day life in a racially stratified society while also having run-ins with the supernatural. Steeped in the African-American spiritual tradition, her characters are at ease when they encounter otherworldly or extraordinary forces. This is especially true of Beloved and Song of Solomon.”

In 2021, Little published Toni Morrison’s Spiritual Vision, in which she examined the ways in which faith, spirituality, a storytelling culture and Morrison’s own feminism intersected and complemented each other in her books. She also noted that despite the often-cruel worlds Morrison’s books explore, they all share another common theme: “Healing—through religious syncretism, racial pride and the wisdom of elders—is the crux of Morrison’s fiction,” she wrote.

“Toni Morrison’s characters always find faith in themselves, in God and in the circumstances of life, without always explicitly naming it as faith,” wrote Boreta Singleton in her review of Toni Morrison’s Spiritual Vision for America. “As Nittle notes, these discoveries lead them to new realizations and moments of deep awareness about life and love. The reader can see God in all areas of Morrison’s characters’ circumstances—in the ‘magic,’ in the pain and suffering, and in the call to healing and wholeness that leads to life.”

In a 2019 tribute to Morrison in America, Tia Noelle Pratt noted how important it was for Black readers to have a writer like Morrison, who did not center her stories from a white perspective or adopt a “white gaze” in her narration. Rather, she sought to give a hearing to the genuine experiences of people who were too often voiceless: “Toni Morrison’s work conveyed the pain, sacrifice and trauma that exemplifies so much of the African-American experience.”

Can we also consider Toni Morrison a Catholic novelist? The hosts of America’s Jesuitical podcast explored this question with Nadra Little in this 2021 episode.

Nadra Little: “Healing—through religious syncretism, racial pride and the wisdom of elders—is the crux of Morrison’s fiction."

•••

Our poetry selection for this week is “A Nun Leaves the Veil,” by Julia Alvarez. Readers can view all of America’s published poems here.

In this space every week, America features reviews of and literary commentary on one particular writer or group of writers (both new and old; our archives span more than a century), as well as poetry and other offerings from America Media. We hope this will give us a chance to provide you more in-depth coverage of our literary offerings. It also allows us to alert digital subscribers to some of our online content that doesn’t make it into our newsletters.

Other Catholic Book Club columns:

Theophilus Lewis brought the Harlem Renaissance to the pages of America

William Lynch, the greatest American Jesuit you’ve probably never heard of

The Catholic faith (and pessimism) of J.R.R. Tolkien

Parish priest, sociologist, novelist: The many imaginations of Father Andrew Greeley

Leonard Feeney, America’s only excommunicated literary editor (to date)

Joan Didion: A chronicler of modern life’s horrors and consolations

Happy reading!

James T. Keane