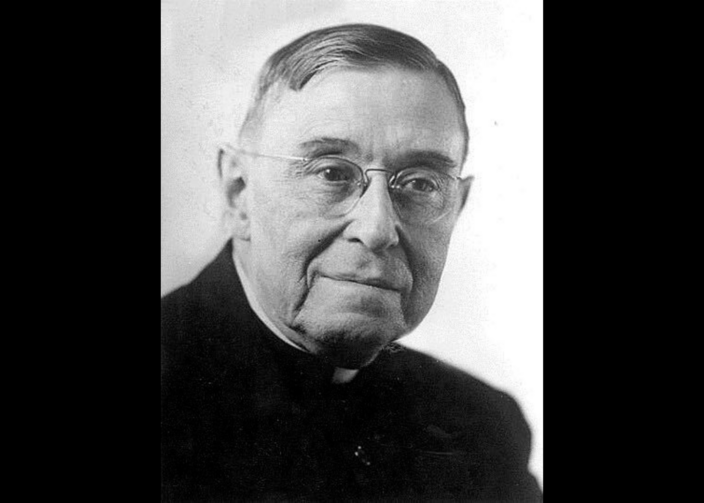

When America was celebrating its centennial year in 2009, Jim McDermott and I wrote a series of articles on notable figures in the magazine’s history, including one on John LaFarge, S.J., a longtime editor (including a four-year stint as editor in chief from 1944 to 1948). Soon after the article’s publication, I received a note from a former Jesuit who had lived with Father LaFarge at America House while pursuing doctoral studies at Columbia University.

He had an embarrassing story to tell. In August of 1963, the rector of the Jesuit community had asked him to accompany the elderly LaFarge to Washington for a civil rights protest. He begged off on the grounds that he had too much academic work to do. A few days later, the front page of The New York Times featured a photo of Martin Luther King Jr. delivering his famous “I Have A Dream” speech at the March on Washington. Among the dignitaries sharing the steps of the Lincoln Memorial with Dr. King? John LaFarge, S.J.

Writing about his experience at the March on Washington, LaFarge called it “as tranquil and inevitable as God’s providence itself, with the majesty and power of an apocalyptic vision."

The erstwhile graduate student admitted in his note that he had spent the next 46 years kicking himself for his foolishness: His studies could have waited for another day, but instead he had missed out on one of the most momentous occasions in modern American history.

LaFarge’s presence with Dr. King made a certain amount of sense; from the 1930s through the 1960s, he was one of the nation’s most recognizable advocates for racial justice, penning hundreds of articles and numerous books on the subject, including 1937’s Interracial Justice: A Study of the Catholic Doctrine of Race Relations. That book inspired Pope Pius XI to ask LaFarge to help write an encyclical on racism, “The Unity of the Human Race” (“Humani Generis Unitas”). The encyclical was never released, likely because the pope feared it would further intensify the persecution of the Catholic Church in Nazi Germany.

Born in 1880 into one of the nation’s most distinguished families (his father, also John, was a renowned artist with stained glass; two of LaFarge’s siblings, Oliver Hazard Perry LaFarge and Christopher Grant LaFarge, became famous architects, and his nephew Oliver LaFarge won the 1929 Pulitzer Prize for his novel Laughing Boy), John LaFarge graduated from Harvard in 1901 and was ordained a priest in 1905, joining the Jesuits shortly after. Though he wanted to become a professor, he suffered from poor health during the course of his formation; as a result, instead of being sent to graduate studies, LaFarge was assigned to be an assistant pastor in various parishes.

LaFarge was sent in 1911 to St. Mary’s County, Md., a rural area with a large population of African Americans where the Jesuits had first established mission churches in 1634. (For many years, the Jesuits of the region had themselves owned a number of slaves.) The economic and social struggles of his African American parishioners had a powerful impact on LaFarge, and working for racial justice would become his primary ministry when he came to America in 1926.

Pope Pius XI asked John LaFarge to help write an encyclical on racism, “The Unity of the Human Race” (“Humani Generis Unitas”).

In 1934, LaFarge founded the Catholic Interracial Council of New York; by 1960, there were 42 Catholic Interracial Councils around the United States, and they were popular with political activists and college students as an avenue for interracial dialogue. LaFarge was frequently sought out as a lecturer; he also published several more books, including The Race Question and the Negro (1943) and Race Relations (1956).

By the time of the March on Washington, LaFarge’s influence in the Civil Rights movement had waned, in part because of his advanced age but also because he promoted a more gradual, moderate approach to civil rights issues than many of his peers in the movement. He died just a few months after the march at the age of 83.

Writing in America in 1963 about his experience at the march, LaFarge called it “as tranquil and inevitable as God’s providence itself, with the majesty and power of an apocalyptic vision. This was the only expression that occurred to my mind, as I gazed over the immense throng stretching all the way from the Lincoln Memorial to the distant Washington Monument—a humbly yet proudly rejoicing multitude of Negroes and whites, responding magically to speakers and singers alike.” Attendees at the march, LaFarge wrote, were certain of two things:

that the demonstration’s aims were completely reasonable, in line with the nation’s oldest and best traditions; and that these aims were certain of fulfillment. The certainty was born of American pride in our country and its heritage. And the marchers were claiming their heritage. As in ancient Israel, their hope was in the God of justice and love.

The march, he concluded, “was but a beginning, a summons to unceasing effort. The hour is bound to come—and the less delay the better—when North and South alike will set a final seal upon its simple goal of jobs and freedom for all citizens—yes for all.”

"The hour is bound to come—and the less delay the better—when North and South alike will set a final seal upon its simple goal of jobs and freedom for all citizens—yes for all.”

•••

Our poetry selection for this week is “Elegy, Written in a Soccer Field,” by Lynne Viti. Readers can view all of America’s published poems here.

In this space every week, America features reviews of and literary commentary on one particular writer or group of writers (both new and old; our archives span more than a century), as well as poetry and other offerings from America Media. We hope this will give us a chance to provide you more in-depth coverage of our literary offerings. It also allows us to alert digital subscribers to some of our online content that doesn’t make it into our newsletters.

Other Catholic Book Club columns:

Theophilus Lewis brought the Harlem Renaissance to the pages of America

William Lynch, the greatest American Jesuit you’ve probably never heard of

The spiritual depths of Toni Morrison

Leonard Feeney, America’s only excommunicated literary editor (to date)

Joan Didion: A chronicler of modern life’s horrors and consolations

Happy reading!

James T. Keane