This essay is a Cover Story selection, a weekly feature highlighting the top picks from the editors of America Media.

In literature, the anxiety of influence always dies hard, but a beautiful wake—worthy of the Irish—sometimes follows its passing. Once we confess how much we owe to an inheritance we did nothing to earn, we can celebrate with greater lucidity and appreciation that which is newly invented.

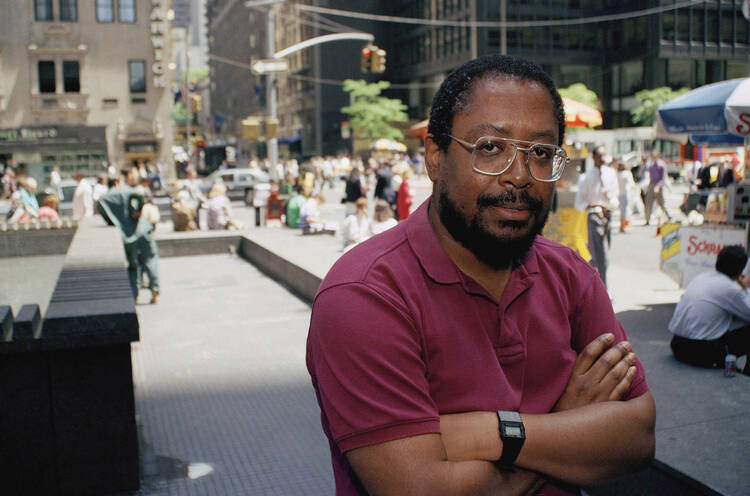

In the years after Edward P. Jones garnered acclaim for his debut short story collection Lost in the City, he buried James Joyce’s Dubliners under an appreciative but faded pall—a “(nearly) nothing to see here” nod. In 1993, when Jones’s collection was a wee year old, an interviewer alleged: “Some reports discuss the fact that you were inspired by Joyce’s Dubliners when you wrote Lost in the City, but you exchanged Dublin for Washington D.C., and you interchanged Irish denizens for African-Americans.” Jones confesses to having “read Dubliners when I was a sophomore at Holy Cross and I liked it very much,” but he insists that “Lost in the City is not patterned after Joyce’s book.” No, “None of them are patterned on stories in Dubliners.”

By 2012, Jones’s circumspection eased. At the College of the Holy Cross, he studied under Maurice Geracht, who, Jones wrote in Lost in the City, “pointed across the ocean to the east where dwelled Joyce’s Dubliners.” Jones admitted that year to “admiring Joyce’s bold and evident love of his Dublin people; I knew all the people in that book because they weren’t doing anything different than what black people in Washington, D.C., were doing.”

The grandness of Dubliners mingled with what Jones called “the ignorance of the whites at Holy Cross” in Lost in the City. Jones turned on the stove of his “secret room”—the Washington, D.C., of his soul—and he began to percolate the stories that would become Lost in the City. Dubliners “planted a molecular seed of envy in me, made me later want to follow Joyce and do the same for Washington and its real people.” He even arranged the stories so that, like Dubliners, they begin with younger characters; as the collection unfolds, increasingly older characters inhabit the stories.

Edward P. Jones is rarely read as a “Catholic writer,” perhaps because shortly after he won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction for his novel The Known World in 2004, he stated, “I’m not a religious man at all.” But when Lost in the City was named a finalist for the National Book Award, Jones declared, “I am Catholic.” It shows. Like the haunted Dublin of his forebear James Joyce, Jones’s Washington, D.C., is visited by spiritual powers left off the tourist maps. Both Joyce’s and Jones’s stories move us through tragic epiphanies that leave the soul, pained by paralysis, on the threshold of conversion. Both ask us to peel our eyes open with pity for their people.

Jones’s own aesthetic could be encapsulated in Joyce’s praise of art that strengthens our “sense of mercy for all creatures who live, die, and yield to their illusions.” The clearest connection across the collections is between Joyce’s “The Dead” and Jones’s “Gospel,” both of which have crucial scenes that feature falling snow.

Joyce and ‘The Dead’

The end of “The Dead” features some of the most famous, most sublime sentences in modern English literature. Gabriel Conroy, a middle-aged husband given to self-absorption and rationalized snobbery, is impatient to exit a dinner party, but something is detaining his wife, Gretta, from leaving. This con of a king (Conroy) champions the hostess’s charity as a “princely failing”—unwittingly providing us with a portrait of himself.

At last, Gabriel finds a woman “standing near the top of the first flight, in the shadow also,” listening to a singer who, in spite of bad congestion, is beautifully belting out “The Lass of Aughrim.” Startled, he sees that the woman “was his wife…. There was grace and mystery in her attitude as if she were the symbol of something.” Caught up in the romance and in her beauty, he dubs her “Distant Music,” setting off a series of ironic reversals that propel him toward a final snowfall anticipated by the snowflakes stuck to his galoshes from the first page:

…snow was general all over Ireland. It was falling on every part of the dark central plain, on the treeless hills, falling softly upon the Bog of Allen and, farther westward, softly falling into the dark mutinous Shannon waves. It was falling, too, upon every part of the lonely churchyard on the hill where Michael Furey lay buried. It lay thickly drifted on the crooked crosses and headstones, on the spears of the little gate, on the barren thorns. His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.

Before this communion with the dead and after his romanticized vision of his wife, Gabriel followed Gretta to their hotel room thrilled by a “keen pang of lust,” only to find her falling to the bed in tears. The catharsis leads her to confess a secret she had kept from her husband until now: Her childhood sweetheart Michael Furey, doomed to die young from consumption, threw a stone at her window and sang, sickly, “The Lass of Aughrim” before, she says, “he died for me”—for the chill he catches while standing outside singing results in his death. Her romantic interpretation of Michael’s passing is a knife in the portrait of “Distant Music” Gabriel was caught up contemplating.

Gabriel receives an epiphany that reveals to him the core of his being as a “well-meaning sentimentalist, orating to vulgarians and idealising his own clownish lusts.” Michael (named, like her husband, after an archangel) may arrive, like the furies of Greek tragedy, to take revenge on the protagonist’s sins, but even if Gretta’s image of the dead 17-year-old may be mingled with a sentimentality that protects her against her husband’s spiritual and emotional impotence, the ghost has something holy about him: “He had never felt like that himself towards any woman, but he knew that such a feeling must be love.”

How can we help but connect Michael’s death with Christ’s maxim of martyrdom: “Greater love has no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends” (Jn 15:13)? As “generous tears” wet his eyes, Gabriel sees in the “form of a young man standing under a dripping tree” a goad to love, reversing his familiar insecurity and self-justifying paralysis.

Jones and ‘Gospel’

From the start, Jones’s “Gospel” is a clear grandchild of Joyce’s “The Dead,” but the genes are rearranged with such freshness that it is far from being a derivative pastiche. The story emerges as a perfect embodiment of the paradox insisted upon by T.S. Eliot: “We shall often find that not only the best, but the most individual parts of his work may be those in which the dead poets, his ancestors, assert their immortality most vigorously.” Preserving the central power of music as seen in “The Dead,” Jones writes the story from the viewpoint of a Black gospel singer named Vivian L. Slater, whose husband, Ralph, is so handsome and apparently healthy that no one suspects he is dying of cancer.

Vivian and her fellow “Gospelteers” perform their typical Sunday singing duties with an interior spiritlessness akin to Gabriel’s—never mind the applause they summon. On the way home from church, her friend Diane stops the car and makes tracks across “an inch or so of snow,” which has fallen all across D.C. A man in a car—her own Michael Furey?—appears to be waiting. We remember, suddenly, that earlier that morning Diane “gave her husband a passionate kiss on the lips, a kiss that Vivian thought was too much for a Sunday morning at the kitchen table,” and as Diane leans in “the kiss came in the dark, the two figures silhouetted against the dull light in the area behind the car.”

When Diane returns, Vivian greets her with fury. But she later recollects the way the mystery man took off his hat in deference to Diane. No, “she had not seen a man take off his hat in that old-fashioned way in a long, long time,” and the gesture sets off a nostalgic dream of childhood and the bygone years of her earlier marriages when men—like the snow that fell universally on the just and the unjust of the city—tipped their hats to a woman’s beauty. Obsessively, “she could still see him,” and though she first disapproves of her friend’s mystery man, Vivian’s fascination snags and she wonders: “How much more grandness, beyond the gesture with the hat, there was to him?” One of the elders is not so sentimental. She says Diane “sure is playin with fire.”

“She could see him,” we hear in near repetition, but now the “him”is her sick husband Ralph, who she’ll find “asleep in the same chair she had left him in that morning.” Likely he “peed on himself again,” and likely he is drunk, his empty bottles dirtying the TV table. Gone, suddenly, is the opening image of a husband who warned her that snow might complicate the weather, the “man who loved profoundly,” who “had not stopped looking at her since she came into the room” and who had brought her fresh ice and drinks as she relished in her ritual Sunday bath.

Unlike “The Dead,” with its epiphany of empathy wherein Gabriel’s soul finds communion with his romanticized rival Michael under snow faintly falling over imagined symbols of torture, “Gospel” announces the fate that awaits the one who will not die to self:

The snow now covered the windows of her car and all she could make out were shadows moving about. She could hear voices, but she could not understand any of what people said, as if all sound were being filtered by the snow and turned into garble.

Her idle car grows colder “and colder still, and at first she did not notice, and then when she did, she thought it was the general condition of the whole world, owing to the snow, and that there was not very much she could do about it.” She had been trying to muster the gumption to “go home to Ralph,” but her final resignation is filled with a cold-hearted reticence.

When Gabriel’s lust for Gretta is cut short and he reaches into the regions of the dead, he can only vaguely “apprehend, their wayward and flickering existence.” But unlike Vivian, whose soul dwells in garbled misunderstanding, Gabriel—guided by “generous tears”—closes the distance between him and his fellow human host. The snow in “Gospel” covers all in confusion instead of communion. Vivian’s nostalgic pangs do not serve as a salutary sentimental education. Instead, the chasm between her high illusions and her handsome, dying husband increases. He looks so good that folks cannot fathom that when she returns, “he would not be able to remember what he had seen throughout the day.”

The distance between Vivian and the dead past also increases: Her recollection of the bygone men only reinforces how irretrievable they are, even as the very memory of their “grandness” condemns all contemporary men. (Sadly, she is not entirely wrong: One of the story’s recurrent characters, Counsel, is a womanizer bereft of the manners she so misses.)

The distance between the gospel music and the women who sing it is greater than anything else in the story, which begins ironically with Vivian in the bathtub “as the House of the Solitary Savior Baptist Church burned to the ground.” Vivian’s name—meaning “life,” from the Latin vivus—bespeaks her hypocrisy. Certain that she has “outgrown a storefront like the House,” accustomed to bigger checks from marquee churches padded with money, Vivian comes back to sing there every Sunday because, back in the day, she received her first break from its founder, Reverend Saunders.

Although “Gospel” announces the storefront church fire in its opening sentence, when the event is narrated midway through the story the actual decimation is anti-climactic because Vivian is indifferent to its ruins. The contrast between the soulful and much-applauded Gospelteers’ songs and the “dead men’s bones” (Mt 23:27-28) they carry within is clearly tied to the burned-down church. Solitary, without a savior, Vivian bears away the epiphanies Jones lets the readers witness, revealing by negation the good news that links the living and the dead.