What’s the best book ever written about Jesus?

Zero points for answering “The New Testament,” like this is a “Peanuts” cartoon circa 1966. Plenty of our readers might point to Jesus: A Pilgrimage, by America’s editor at large, James Martin, S.J., but Father Martin has his own opinion on the subject. He’s backed up by the G.O.A.T. when it comes to New Testament studies, the late Daniel Harrington, S.J. Father Harrington, who forgot more about the Bible than most of us will ever learn, had a definitive ruling that Father Martin shared: The best book ever written about Jesus is Jesus of Nazareth: What He Wanted, Who He Was.

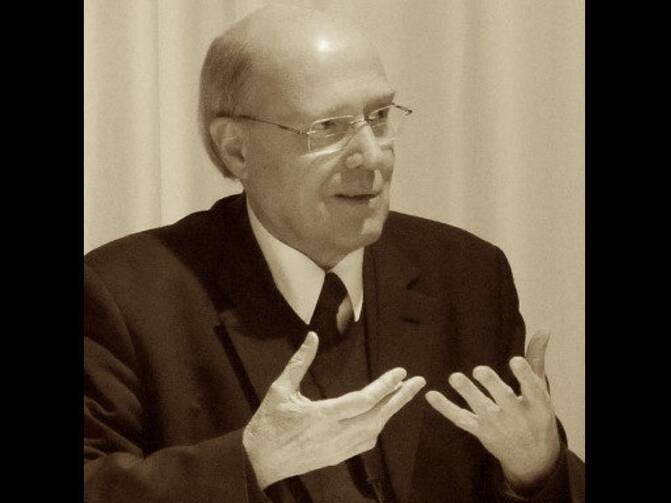

The author, Father Gerhard Lohfink, died last week in his native Germany at the age of 89. He leaves behind an impressive legacy of faith-informed scholarship on the New Testament and Christian discipleship. Among his best-known works on this side of the pond are translations of Jesus of Nazareth, Is This All There Is? On Resurrection and Eternal Life, The Forty Parables of Jesus,No Irrelevant Jesus and Does God Need the Church? He died after a short illness on April 2, 2024.

I was working for Orbis Books when Liturgical Press came out with an English translation of Jesus of Nazareth in late 2012—just in time to make quite a splash at the American Academy of Religion’s annual meeting—and it is safe to say we at Orbis were a little jealous.

For Father Martin, part of the appeal of Jesus of Nazareth was that Lohfink didn’t fall into the easy trap of contrasting the “Jesus of history” with the “Christ of faith,” a trope of sorts in New Testament scholarship in a previous generation. Lohfink, Martin wrote in an appreciation for America last week, “saw no contradiction between the two, and a good deal of the book not only reflects on what the Gospels mean for contemporary Christians, but reminds readers of the historicity of the one in whom we believe.”

In a 2013 America column, Martin also noted how refreshing he found Lohfink’s refusal to accept smug contemporary views of the Gospels. “How often have you heard, for example, that the multiplication of the loaves and the fishes was simply an example of sharing? Or that the resurrection was simply a ‘shared experience’ of the disciples’ remembering Jesus?” Martin wrote. “Lohfink has little sympathy for this: ‘It is a way of currying favor with the Enlightenment mentality, which wants to explain away everything unusual.’ That no one has stilled storms before or since is not an argument against the authenticity of the Gospels so much as an example of Jesus as someone who was, as Lohfink says, ‘irritatingly unique and therefore can surpass all previous experience.’”

In a 2013 review for America, the New Testament scholar Thomas Stegman, S.J. (who passed away last year), offered further praise. “Lohfink’s portrait of Jesus is very much worth reading. Because he looks to the Gospels with a sympathetic yet critical eye, he gives a faithful interpretation of Jesus,” wrote Stegman, who also reviewed Lohfink’s 2018 book on the afterlife, Is This All There Is? “And because he is faithful, Lohfink offers a portrait that is challenging—especially for the church today.”

Born in 1934 in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, Lohfink was ordained in 1960 and earned a doctorate in theology in 1971. From 1973 to 1987, he was a professor at the University of Tübingen—where he was involved in a controversial decision to exclude the theologian Hans Küng from the faculty after the Vatican revoked Küng’s canonical status to teach theology in a Catholic school in 1979. In 1987, Lohfink left Tübingen and joined the Catholic Integrated Community, an association of lay Catholics based in Bad Tölz in what was then West Germany, but continued to publish and lecture on theology until his death.

In 2018, Jesus of Nazareth was a selection of America’s Catholic Book Club (you know, in case the first two articles we published didn’t take). In his introductory essay on the book, Kevin Spinale, S.J., used a curiously timely analogy for us this week (🌖) in describing Lohfink’s theme: He compared it to the total solar eclipse in the United States in August 2017—and specifically to the word “totality.” That notion, he wrote, “seems to characterize Lohfink’s portrait of Jesus in several ways. First, Lohfink emphasizes that Jesus’ life is a historic event: visible and tangible, as dramatic and concrete as an eclipse. Second, Lohfink argues that Jesus’ life and the way he understood himself need to be interpreted through the totality of the canonical Scriptures, particularly the texts of the Old Testament.”

In 2012, Lohfink himself appeared in America with “Everyday Disciples: The many ways to be called,” an edited excerpt from Jesus of Nazareth. He drew parallels between Jesus’ calls to discipleship in the Gospels and the current diversity of ministries and vocations in the church. “The more closely we read the Gospels, the clearer it appears, over and over again, that the various ways of life under the reign of God do not arise out of accidental circumstances but are essential to the Gospel,” Lohfink wrote. “We have to look deeper. Ultimately, the variety of callings is a precondition for the freedom of every individual within the people of God.”

Lohfink also had strong words for those Christians—of any ideological stripe—who see themselves as the “true believers.” Jesus, he wrote, wouldn’t have had much time for such nonsense:

The division of the church into perfect and less-than-perfect, into better and ordinary, into radical ethos and less radical ethos, ignores the unity of the people of God and the organization of all its members toward the same goal.

•••

Our poetry selection for this week is “That Early-Eastering Crocus,” by Paul Mariani. Readers can view all of America’s published poems here.

Also, news from the Catholic Book Club: We have a new selection! We will be reading Norwegian novelist and 2023 Nobel Prize winner Jon Fosse’s multi-volume work Septology. Click here to buy the book, and click here to sign up for our Facebook discussion group.

In this space every week, America features reviews of and literary commentary on one particular writer or group of writers (both new and old; our archives span more than a century), as well as poetry and other offerings from America Media. We hope this will give us a chance to provide you with more in-depth coverage of our literary offerings. It also allows us to alert digital subscribers to some of our online content that doesn’t make it into our newsletters.

Other Catholic Book Club columns:

The spiritual depths of Toni Morrison

What’s all the fuss about Teilhard de Chardin?

Moira Walsh and the art of a brutal movie review

Who’s in hell? Hans Urs von Balthasar had thoughts.

Happy reading!

James T. Keane