Like many other films that suffered financially during the Covid-19 pandemic, Scott Loudon’s documentary on the music of the Jesuit reductions in South America stalled. But the project never died. Loudon’s faith as a Protestant evangelical and a former missionary, along with his passion for these missions, helped him focus on God’s providence even in light of setbacks.

“I may not have the resources at a given moment,” explains Mr. Loudon, a Detroit-based filmmaker and sound engineer, “but God provides.”

With financial support from friends, Loudon traveled this week to Bolivia for the 14th biennial International Festival of Renaissance and American Baroque Music “Misiones de Chiquitos,” which runs from April 19-28 in Santa Cruz and the Chiquitania region of eastern Bolivia. Filming the festival—his first—represents a culmination of musical footage he has been recording over eight years as he became more immersed and intrigued with the historic encounter between Jesuits and the Indigenous populations of the reductions.

The music festival is produced by La Asociación Pro Arte y Cultura (APAC), a nonprofit cultural organization that aims to promote and produce artistic initiatives especially related to the Chiquitos missions, which the Jesuits established between 1691 and 1760. It is the largest festival of its kind attracting 1,200 musicians from 15 countries who will perform 130 free concerts in 22 venues over the course of 10 days.

Some of the world’s most prestigious ensembles and music schools—like Juilliard and the Royal Conservatory—will perform for and alongside mission orchestras. This year, two American Jesuit universities will participate: Georgetown University’s Chamber Choir will sing selected repertoire in five of the mission churches, and Boston College’s Clough’s School of Theology and Ministry will sponsor the world premiere of the opera “San Francisco Xavier” in the San Xavier and Concepción missions, respectively.

Loudon’s research adds an important piece to the ongoing story of the Jesuit reductions made popular in part by Roland Joffé’s critically acclaimed 1986 film “The Mission.” But as Loudon clarifies, his documentary continues where Joffé’s film ends. In that final scene, where anti-Jesuit soldiers nearly massacred a community of Guaraní Indians and the local Jesuits, a surviving Guaraní girl retrieves a violin awash on the riverbank and carries it into a boat where she and other children leave for a new settlement. As the credits roll, Joffé implies that while the Jesuit effort was essentially destroyed, music would play an important part in the children’s future.

With the papal suppression of the Jesuits in 1773, many assumed that the chapter of reduction history would end. That was certainly the case for the missions in Paraguay, Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay whose ruins are now museums and tourist destinations. The Bolivian reductions, by contrast, tell a different story. With the exception of San Ignacio de Moxos in Beni where the Jesuits returned to minister more than 150 years after their restoration in 1814, other religious orders—particularly the Franciscans—have staffed these parishes, which have survived until this day. In 1990, Unesco declared six of these churches as world heritage sites, which represents a collective effort inspired in part by the Swiss architect and former Jesuit Hans Roth, who attracted international support for his quest to repair and renovate those deteriorating structures from 1972 until his death in 1999.

Also unknown to many, the musical legacy endured, though initially Westerners did not know what it sounded like. So when Ennio Morricone composed the score to Joffé’s film he was particularly mindful of reflecting the spirit of that encounter—by blending Western and Indigenous sounds—to create what has become an enduring soundtrack.

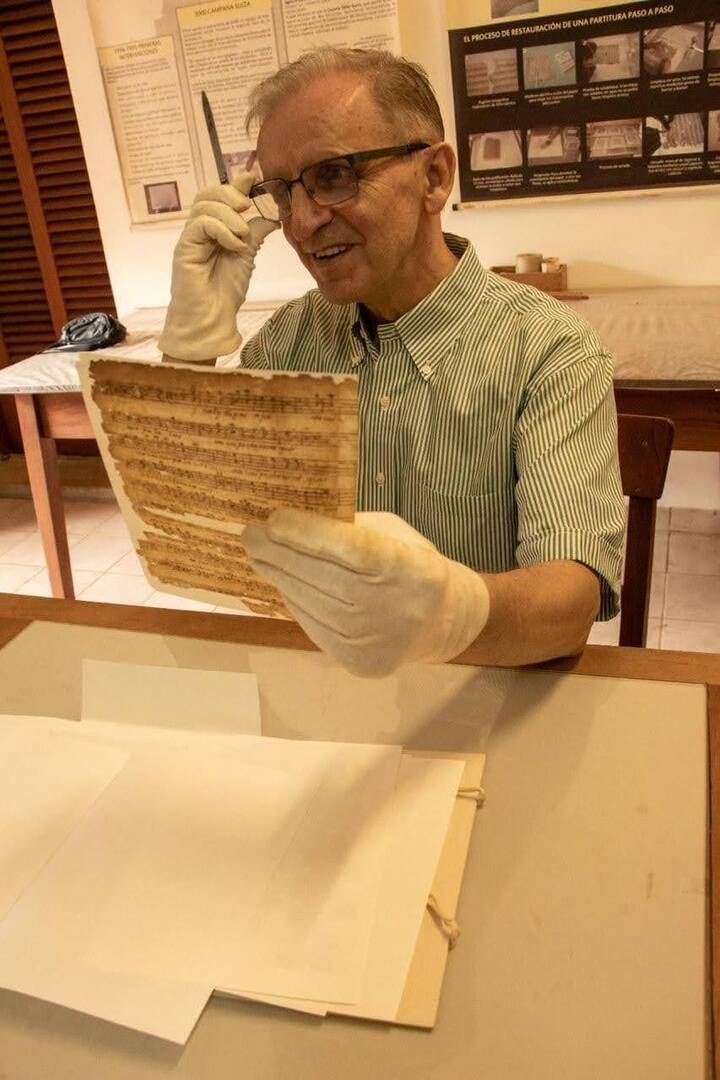

Ironically, around the release of the film, the Moxos and Chiquitano elders started sharing their music collections with Western musicologists. Among those scholars included Boston College Jesuit T. Frank Kennedy, S.J., and Piotr Nawrot, S.V.D., a Divine Word Missionary from Poland who would spend more than 30 years in Bolivia studying, restoring and promoting the music, which would eventually be housed in two archives: San Ignacio de Moxos and Concepción Cathedral in Chiquitos.

Before seeing the Moxos scores, Nawrot recalled local elders interrogating him. “For three hours they questioned me about my faith, my religion,” Father Nawrot explained. This “complete reversal of roles,” he reflects, points to the significance of music in their lives: “It was like the Ark for the Jews; no matter where they moved, they took this sacred music. For them this music is not just sound and harmony—this is the history of their sacred salvation.”

In addition to publishing more than a dozen transcriptions, Nawrot has also been a key animator for APAC’s biennial festivals for nearly 30 years. While the pandemic caused the event to hemorrhage financially, they have been able to regain footing, albeit slowly, and undertake new ventures.

One prominent example is the world premiere of “San Francisco Xavier,” a mission opera sponsored by Boston College. The score, anonymously composed and restored by Nawrot in 2000 with funding from the Guggenheim Foundation, holds the distinction of being the only surviving opera in the collection set in the Chiquitano language. Argentine conductor Gabriel Garrido recorded the work in 2017 with his Ensemble Elyma and the Coro de Niños Cantores de Cordoba—an album easily accessible online. However, this year, the opera will premiere at the mission itself, performed by the parish’s local ensemble: Coro y Orquesta Misional San Xavier. As Nawrot explains, this performance is significant because it will give a rare glimpse into how Jesuits used music for evangelization. We will witness a presentation in the space and with people for whom the opera was initially intended.

This music reflects Jesuit evangelization efforts from the 17th and 18th centuries, however, Percy Añez, APAC’s president, insists they are not museum pieces. The order’s 80-year legacy still has important lessons to teach contemporary audiences—regardless of one’s creed. Añez elaborates: The people have integrated this repertoire into their own cultural identities; for the encounter between Jesuits and the local Indians modeled a “culture of love based on God and expressed through the Christian Catholic tradition.”

In fact, as he recalls a famous homily of Pope Benedict XVI, Añez suggests that the mission music represents a sharp counterpoint to the “dictatorship of relativism” against which the former pope once preached. Where cultures breed duplicity, music reflects truth; in the face of superficiality, music offers authenticity. The suppression of the Jesuits may have changed the missionary landscape of the region, but those seeds are yielding artistic expressions of faith that still testify “that love wins.”