At Citi Field today in Flushing, N.Y., the Los Angeles Dodgers will make a rare appearance in the Big Apple with a doubleheader against the Mets. In first place in the National League West, the Dodgers bring their latest superstar, Shohei Ohtani; they also tend to draw a large (and hostile) crowd in New York. In the interest of not having a beer dumped on my head, I am not wearing my Dodgers jersey to today’s games. (Also, it doesn’t fit me anymore.)

I have argued much about my beloved Dodgers with fellow America editors and the occasional Jesuit who grew up cheering for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Many had never forgiven Walter O’Malley for moving the team to Los Angeles in 1958. One was James “Deej” DiGiacamo, S.J., who taught for many years at the now-closed Brooklyn Prep. (Alums of Brooklyn Prep are even madder about that than they are about the Dodgers leaving.) Among Deej’s accomplishments: teaching a young John Sexton, later president of New York University from 2001 to 2015, to memorize “Meet the Mets”...in Latin. A sample, as related in a New Yorker profile of Sexton published in 2013, less than two weeks before Deej died:

Occurrite Mettibus, occurrite Mettibus

Veniamus, occurramus Mettibus…

I accompanied Deej to the first game in the new Yankee Stadium in 2009, for which he had somehow procured tickets in the second row. He was 84 at the time. Deej was a great seatmate for baseball, as he had an encyclopedic memory of a sport he had been watching for the better part of a century. Still a high school teacher at heart, he also spent much of the game ordering the finance bros in the first row to sit down and stop blocking his view. It was a spicy afternoon.

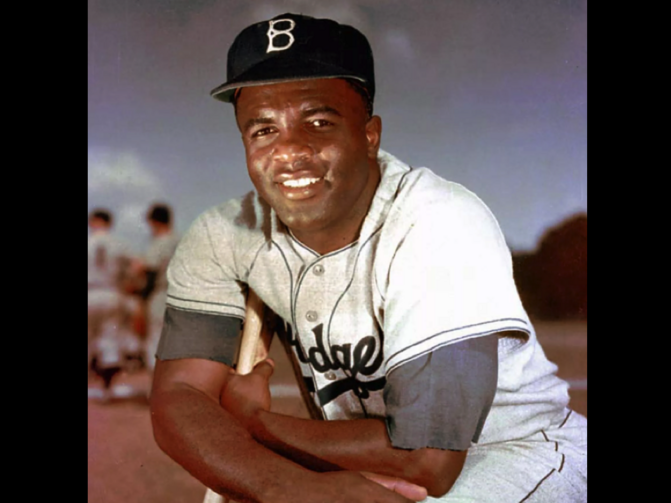

In 1998, Father DiGiacamo reviewed Arnold Rampersad’s biography of Jackie Robinson, the Dodgers phenom who broke the color barrier in Major League Baseball in 1947. “The struggles, the hits and runs, the championships won and the victories and defeats experienced on the ball field are depicted on a larger canvas as one man’s untiring quest for justice for his people and of a nation’s attempt to realize its own ideals and to be true to its best collective self,” he wrote in America. “To read the life of Jackie Robinson is to relive the story of an entire people, black and white, in their stormy, still unfinished struggle to achieve justice and reconciliation. His great achievement was not only that he was a part of that struggle but that he even helped make it happen.”

Born in 1919 in Cairo, Ga., Robinson grew up in Pasadena, Calif., and was a four-sport star at U.C.L.A. He was drafted into military service after college and commissioned as a second lieutenant. Court-martialed for refusing to move to the back of an Army bus, he was later acquitted and received an honorary discharge. After briefly flirting with a football career (his best sport at U.C.L.A.), he was signed by the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro Leagues in 1945.

The next year, Branch Rickey, the general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, signed Robinson to play for the team’s minor-league affiliate, the Montreal Royals. He intended to make Robinson the first Black player in modern Major League Baseball, which had been segregated for more than six decades. According to reporters, Rickey asked Robinson if he would be willing to endure the racial abuse sure to come, and told him that he needed a player “with guts enough not to fight back.”

Called up to the Brooklyn Dodgers to start the 1947 season, Robinson immediately became the target of open and vicious racism from players and fans alike. When players from the St. Louis Cardinals threatened to strike rather than play against Robinson, National League Commissioner Ford Frick responded vigorously:

If you do this, you will be suspended from the league....I do not care if half the league strikes. Those who do it will encounter quick retribution. All will be suspended, and I do not care if it wrecks the National League for five years. This is the United States of America, and one citizen has as much right to play as another. The National League will go down the line with Robinson, whatever the consequences.

In a 1947 editorial, America’s editors praised Frick’s outspokenness. “Mr. Frick’s words will hardly, of course, work any change of heart in the disgruntled ball players. But they do ensure that the gate of opportunity, opened by the Brooklyn Dodgers, will remain open,” they wrote. “They enlist the whole strength of the National League in the cause of justice and equal opportunity. They go a long way towards making our national game even more representative of our true national spirit.”

Robinson won the 1947 Rookie of the Year award as the Dodgers took the pennant before losing to the New York Yankees in the World Series. He endured both physical and verbal abuse throughout the season. While the arrival the next year of several more Black players in the majors as well as Robinson’s sterling play (he was the National League’s Most Valuable Player in 1949) ameliorated the situation to some degree, Robinson and others reported continued racist commentary and segregated accommodations in many cities for years to come.

Indeed, Robinson earned many enemies who had no interest in baseball at all. William F. Buckley Jr., who attended only two baseball games in his life, nevertheless had very strong opinions about Jackie Robinson, calling him a “pompous moralizer who whines his way through life as though all America were at Ebbets Field cheering him on against the big bad racist St. Louis Cardinals.” He said far worse in 1968 when Robinson, who had previously supported Richard Nixon's presidential bids, publicly criticized Nixon and the Republican Party, but you can look that up yourself.

Led by Robinson and a growing cadre of young stars (including numerous Black players), the Dodgers continued to fall just short of triumph throughout the early 1950s, finally winning the World Series in 1955 over the hated Yankees. Suffering from ill health, Robinson retired from baseball after the 1956 season to become an executive with the Chock full o’Nuts coffee company, where he became the first Black person to serve as vice president of a major American corporation. The Dodgers departed for the West Coast two seasons later.

In 1962, Robinson was inducted into baseball’s Hall of Fame. In 1972, the year he died, he published an autobiography, I Never Had It Made. In 1997, Major League Baseball retired his jersey number, 42, for all of baseball.

“It seems like only yesterday that Jackie Robinson dashed wildly down the third-base line to steal home against the Yankees in the opening game of the 1955 World Series,” remembered the editors of America in 1977 (another year when the Yankees and Dodgers faced off in the World Series). “As a player he could beat the other team by his hitting, bunting, fielding and stealing. His baserunning would unsettle the opposition and excite the crowd. His fierce competitive drive spurred on his teammates. His brilliant play assured him a place in baseball’s Hall of Fame,” they wrote of Robinson, who had died five years earlier:

But for all that, Jackie Robinson will live on in memory as a man who withstood brutal pressures both within himself and from hostile players and fans to ensure that Branch Rickey’s noble experiment would succeed. Succeed it did. For most athletes, Housman’s somber warning that the name dies before the man proves true. For Jackie Robinson, it is just the opposite. The man may be dead, but the name will live on as a vivid reminder of our bigoted past and as a symbol of hope for racial harmony.

Go Dodgers!

•••

Our poetry selection for this week is “Arise,” by Marjorie Maddox. The author of Rules of the Game: Baseball Poems among many other books, she is also the great grandniece of Branch Rickey, who first signed Jackie Robinson. Readers can view all of America’s published poems here.

Also, news from the Catholic Book Club: We have a new selection! We are reading Norwegian novelist and 2023 Nobel Prize winner Jon Fosse’s multi-volume work Septology. Click here to buy the book, and click here to sign up for our Facebook discussion group.

In this space every week, America features reviews of and literary commentary on one particular writer or group of writers (both new and old; our archives span more than a century), as well as poetry and other offerings from America Media. We hope this will give us a chance to provide you with more in-depth coverage of our literary offerings. It also allows us to alert digital subscribers to some of our online content that doesn’t make it into our newsletters.

Other Catholic Book Club columns:

The spiritual depths of Toni Morrison

What’s all the fuss about Teilhard de Chardin?

Moira Walsh and the art of a brutal movie review

Who’s in hell? Hans Urs von Balthasar had thoughts.

Happy reading!

James T. Keane