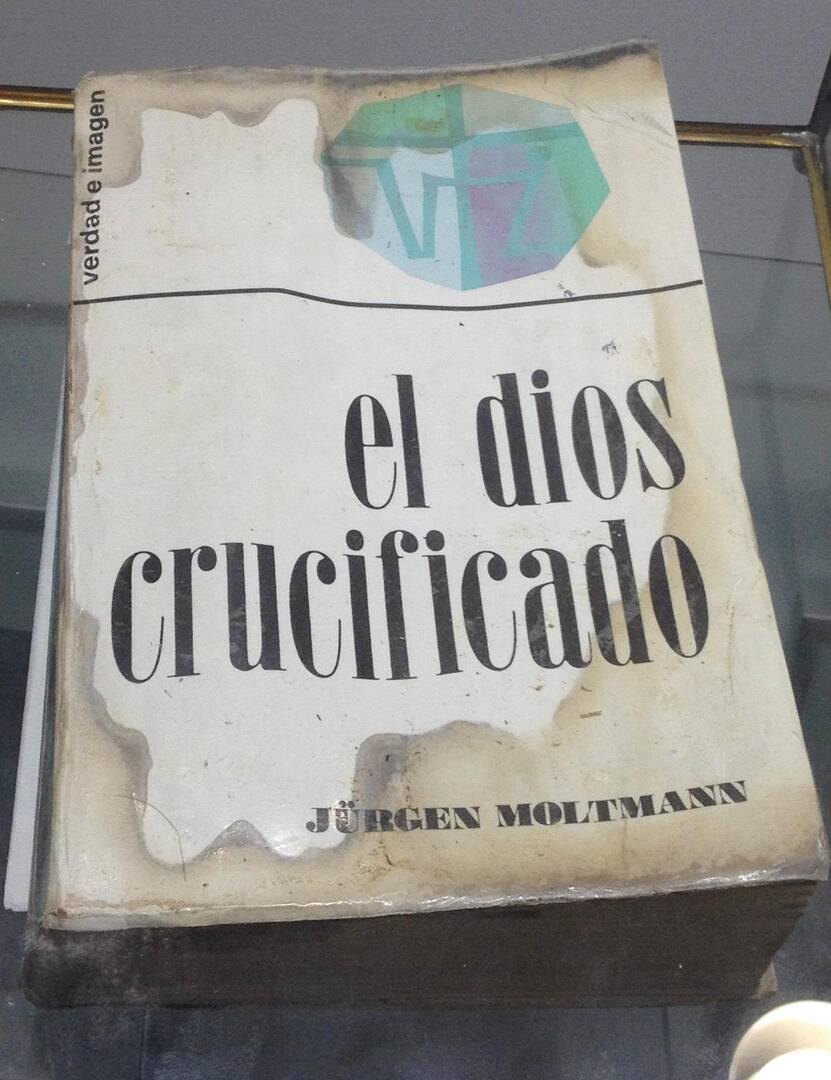

The Centro Monseñor Romero at the Universidad Centroamericana José Simeón Cañas in San Salvador includes in its museum collection a number of the belongings of the six Jesuit priests, their housekeeper and her daughter who were murdered by Salvadoran paramilitaries on Nov. 16, 1989. Among the relics is a book that belonged to one of the martyrs, Juan Ramon Moreno, S.J. It was found next to his body the morning after his murder, stained with his blood.

What’s the book? Jürgen Moltmann’s The Crucified God.

That’s no coincidence. The death of Jürgen Moltmann last week at the age of 98 was noted by both secular and religious journals, a testament to Moltmann’s enormous influence over several generations of theologians and other scholars in related fields. Moltmann was once one of the most prominent theologians in the world—in both Protestant and Catholic thought. After Moltmann’s death, one commenter said that it is “almost impossible to understand modern Protestant theology without reading [The Crucified God].” In liberation theology, he was something of a founding father.

One telling indicator of Moltmann’s importance can be found in a 1972 article in America that was largely critical of theologians of the time. “[L]ike all theory, theology is essentially derivative and secondary,” wrote Russell Barta, a professor of social science at Mundelein College at the time. “The Good News, in short, comes from the Gospel and the mouth of Jesus—not from a Rahner or a Moltmann.”

Remember: You’re nobody until somebody points out you’re not Jesus.

Moltmann was born in 1926 in Hamburg, Germany. Drafted into the German army as a teenager during World War II, he narrowly escaped death during the Allied bombings of Hamburg. He later reflected that his experiences in the war (and in various prisoner-of-war camps after) taught him much about hope and suffering—and about how humanity might find meaning in a deeply inhumane world. In one camp, Moltmann was given a copy of the New Testament and Reinhold Niebuhr’s The Nature and Destiny of Man, a book he later credited with making him want to pursue theology.

Moltmann was born in 1926 in Hamburg, Germany. Drafted into the German army as a teenager during World War II, he narrowly escaped death during the Allied bombings of Hamburg. He later reflected that his experiences in the war (and in various prisoner-of-war camps after) taught him much about hope and suffering—and about how humanity might find meaning in a deeply inhumane world. In one camp, Moltmann was given a copy of the New Testament and Reinhold Niebuhr’s The Nature and Destiny of Man, a book he later credited with making him want to pursue theology.

He received his doctorate in theology from the University of Göttingen in 1952. In 1963, he was hired at the University of Bonn; four years later, he moved to the University of Tübingen, where he would remain as Professor of Systematic Theology until he retired in 1994. He also received visiting appointments at various universities in North America and Europe.

Moltmann authored more than 40 books, including his famous trilogy Theology of Hope (1964), The Crucified God (1972) and The Church in the Power of the Spirit (1975) and a later series of “systematic contributions,” including The Trinity and the Kingdom, God in Creation, The Way of Jesus, The Spirit of Life, The Coming of God and Experiences in Theology.

In Theology of Hope, Moltmann began to lay out his “Kingdom of God” eschatology, one based on hope in the resurrection but more focused on the here and now than any final or individual judgment. He also rejected any notion that Christianity could be reduced to an individual’s personal quest to achieve salvation. “If Christian hope is reduced to the salvation of the soul in a heaven beyond death, it loses its power to renew life and change the world, and its flame is quenched,” he later wrote, a sentiment central to liberation theology as well.

Moltmann was deeply influenced by the German philosopher and social critic Ernst Bloch’s Marxist-tinged “philosophy of hope,” though Bloch’s work was rarely translated into English for many years, making Moltmann’s “theology of hope” the introduction to Bloch’s insights and influence for many English-speaking theologians.

Because Moltmann also stressed that God’s action in the resurrection offered the promise of salvation for all, his theology provided a base for many emerging liberation theologians who would stress the church’s preferential option for the poor. While Moltmann believed that salvation history would ultimately include reconciliation of the oppressor with the oppressed, the liberation of the latter took precedence. He also believed strongly that any theology or the cross or the resurrection was by its nature political theology, in that it could not accept the status quo or claim that salvation was possible outside of history—a contention similar to that of his Catholic counterpart Johann Baptist Metz.

In The Crucified God, Moltmann suggested—contra to most Christian theology—that God the Father suffered in Jesus’ earthly Passion and that the crucifixion is part of God’s identification with human suffering overall. If you’re a heresy-hunter, it sounds like patripassianism or modalism; but if you seek in a post-Holocaust world to understand how God allows such enormous suffering, it offers an interpretive key of sorts.

The Crucified God was reviewed in America in 1972 by Leo O’Donovan, S.J. (himself a former student of Rahner), who noted Moltmann’s engagement with the “Frankfurt School” of critical theory, including Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno, and wrote that Moltmann “examines our common past for the source of our future hope of resurrection. His focus is on God’s identification, through the cross of Christ, with the sufferings of man.” O’Donovan summarized Moltmann’s argument in The Crucified God as a question: “How can we find a human God in a dehumanized world?”

Moltmann’s original “trilogy” brought him into prominence in the world of theology and allowed him to influence several generations of students and colleagues and to introduce his theological ideas to a broader world. In 1968, he was profiled in The New York Times in a front-page story on the “theology of hope.” (It appeared next to “Political Activism New Hippie ‘Thing.’”) In 1984-85, he delivered the prestigious Gifford Lectures at the University of Edinburgh.

After his wife Elizabeth died in 2016, he wrote Resurrected to Eternal Life: On Dying and Rising, a meditation on death and the resurrection. It was published in English in 2021.

In the aforementioned 1968 article in The New York Times, a fortysomething Martin Marty (already at the University of Chicago) commented on Moltmann’s thought. It is “a theology that could make a difference in a revolutionary world,” Marty said, continuing:

It could help inform and inspire an uncertain Church. It could force a rethinking of the basic Christian principles and mandates; it could free people from the dead hands of dead pasts.

•••

Our poetry selection for this week is “Trees,” by Greg Kennedy. Readers can view all of America’s published poems here.

Also, news from the Catholic Book Club: We have a new selection! We are reading Norwegian novelist and 2023 Nobel Prize winner Jon Fosse’s multi-volume work Septology. Click here to buy the book, and click here to sign up for our Facebook discussion group.

In this space every week, America features reviews of and literary commentary on one particular writer or group of writers (both new and old; our archives span more than a century), as well as poetry and other offerings from America Media. We hope this will give us a chance to provide you with more in-depth coverage of our literary offerings. It also allows us to alert digital subscribers to some of our online content that doesn’t make it into our newsletters.

Other Catholic Book Club columns:

The spiritual depths of Toni Morrison

What’s all the fuss about Teilhard de Chardin?

Moira Walsh and the art of a brutal movie review

Father Hootie McCown: Flannery O’Connor’s Jesuit bestie and spiritual advisor

Who’s in hell? Hans Urs von Balthasar had thoughts.

Happy reading!

James T. Keane