A sitting president deciding to withdraw from a campaign for another term? When President Joseph R. Biden did just that over this past weekend, plenty of folks called it an unprecedented moment in American politics. The president, we were told, did something unthinkable.

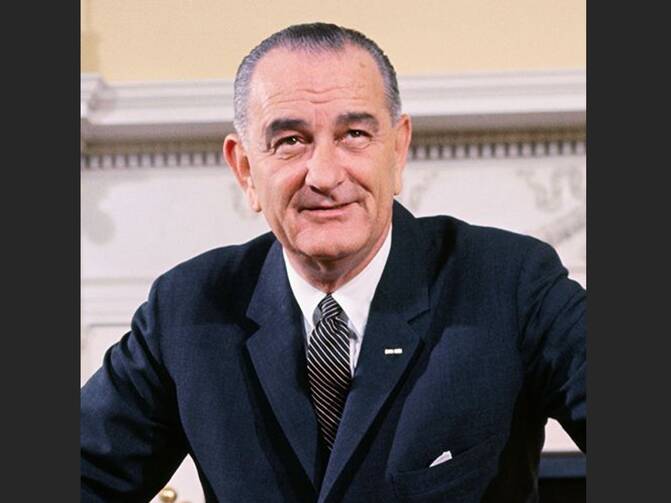

Except he didn’t. It’s happened before. In March 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson proleptically pulled a Biden, announcing he would not seek the Democratic Party’s nomination for the 1968 presidential election. The startling moment ushered in a chaotic season in American politics, as the Democratic campaign became a three-way race between Robert F. Kennedy, Eugene McCarthy and Hubert Horatio Hornblower Hubert Humphrey, with erstwhile Democrat George Wallace also in the race. Humphrey eventually became the Democratic nominee.

Johnson framed his departure from the race as an attempt to restore unity to a fragmented nation. He had assumed the presidency upon the assassination of John F. Kennedy in 1963, then was re-elected in 1964 in a landslide victory over the Republican nominee, Barry Goldwater. Though history remembers him for the Civil Rights Act, the War on Poverty and the Great Society programs (he also created Medicaid and Medicare), his presidency foundered over the increasingly unpopular war in Vietnam and the civil unrest the war and other societal issues had sparked in the United States.

On March 31, 1968, President Johnson gave a televised public address that seemed at first to be focused on military actions in Vietnam, where he announced there would be a drastic curtailment in American military activity in the hopes of bringing about peace—or at least a cease-fire. At the end of his speech, however, he turned to the subject of his presidency, noting that 52 months before, he had been thrust into the position of president by Kennedy’s death and had sought since to advance JFK’s policies and vision for America.

“For 37 years in the service of our Nation, first as a Congressman, as a Senator, and as Vice President, and now as your President, I have put the unity of the people first. I have put it ahead of any divisive partisanship. And in these times as in times before, it is true that a house divided against itself by the spirit of faction, of party, of region, of religion, of race, is a house that cannot stand,” Johnson said. “There is division in the American house now. There is divisiveness among us all tonight. And holding the trust that is mine, as President of all the people, I cannot disregard the peril to the progress of the American people and the hope and the prospects of peace for all peoples. So, I would ask all Americans, whatever their personal interests or concern, to guard against divisiveness and all of its ugly consequences.”

Then came the shocker:

I have concluded that I should not permit the Presidency to become involved in the partisan divisions that are developing in this political year. With America’s sons in the fields far away, with America’s future under challenge right here at home, with our hopes and the world’s hopes for peace in the balance every day, I do not believe that I should devote an hour or a day of my time to any personal partisan causes or to any duties other than the awesome duties of this office—the Presidency of your country. Accordingly, I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your President.

The editors of America noted a few weeks later that Johnson’s somewhat surprising departure from form by leaving the race wouldn’t prevent further civil unrest nor bring an end to the war in Vietnam, but they recognized that his motives might be patriotic in part. That year, remember, was a particularly chaotic one for Catholic voters: Johnson had the strong support of Richard Daley of Chicago, which carried with it the loyalty of the unions and many Irish Catholics—but Robert Kennedy and Eugene McCarthy were also closely identified with their Catholic faith and were popular with students, intellectuals and peace activists. Eight years after the election of the nation’s first Catholic president, suddenly there were Catholics cropping up everywhere.

“For the moment,” the editors wrote, “we wish only to emphasize that Mr. Johnson's decision, which testifies, we are sure, to his great love for the country and his deep respect for the Presidency, doesn't change substantially the harsh and pressing problems confronting the nation, which must be resolved if there is to be any solid movement toward peace either at home or abroad.”

However, the editors noted, the country would now hopefully “be less inclined now to accept political partisanship as an excuse for continued inaction and obstruction. In the era of good will that seems to be developing as a result of Mr. Johnson's renunciation, Congress should indeed find it easier to do its duty.”

That August, longtime America columnist and Washington political pundit Mary McGrory compared Johnson’s troubled presidency to the papacy of Pope Paul VI, who had recently released “Humanae Vitae” and was facing significant blowback from every Catholic corner of the globe over that encyclical’s upholding of the ban on artificial birth control. (You can read America’s 1968 editorial on “Humanae Vitae” here.) “The parallel is obviously imperfect, but it may be instructive to explore it,” she wrote.

“Now both the Pope and the President have the daunting task of enforcing policies that are being challenged by respectable and respected elements in their respective flocks,” McGrory wrote. “Breaking with the past is difficult; but not breaking, in these times, appears equally hazardous. The two excruciating questions of war and birth control have become the central issues of the presidency and the papacy respectively. The President and the Pope would both like to be remembered for other things, but they seem unlikely to be.”

The similarity of Johnson’s predicament to that of President Biden is somewhat less obvious—though Biden’s experiences over the past month and his decision not to seek re-election also have a papal parallel. Pope Benedict XVI took a similarly radical step in 2013 and stepped down as pope because of age and his perceived inability to effectively manage the myriad duties of the papacy, as noted by Michael J. O’Loughlin in America yesterday.

Lyndon Johnson served out the rest of his term in office and then more or less left the limelight. He died on Jan. 22, 1973. The news of his death was the headline in The New York Times the next day, beating out the news of a Supreme Court decision that came down the day before: Roe v. Wade. Two days after his death, the man who eventually won the 1968 election was sworn in for what would prove to be a short-lived second term in office: Richard Nixon.

•••

Our poetry selection for this week is “Gaza,” by Kirby Michael Wright. Readers can view all of America’s published poems here.

Members of the Catholic Book Club: We are taking a hiatus this summer while we retool the Catholic Book Club and pick a new selection.

In this space every week, America features reviews of and literary commentary on one particular writer or group of writers (both new and old; our archives span more than a century), as well as poetry and other offerings from America Media. We hope this will give us a chance to provide you with more in-depth coverage of our literary offerings. It also allows us to alert digital subscribers to some of our online content that doesn’t make it into our newsletters.

Other Catholic Book Club columns:

The spiritual depths of Toni Morrison

What’s all the fuss about Teilhard de Chardin?

Moira Walsh and the art of a brutal movie review

Father Hootie McCown: Flannery O’Connor’s Jesuit bestie and spiritual advisor

Who’s in hell? Hans Urs von Balthasar had thoughts.

Happy reading!

James T. Keane