Cambridge, MA. As readers of this blog know, my main theme here is, or should be, interreligious dialogue. And while I am not much into current events, I do frequently enough write about matters that cross religious boundaries. But you will also know, if you’ve been reading my entries over the past four years, that more often than not I am writing simply about us – Christians, Catholic Christians. This is because “the problem of world religions” and the “challenges of dialogue” are mostly in our own heads and hearts. Hindus and Jews and Buddhists and Muslims, pagans and Daoists and Zoroastrians, also come in many forms with many attitudes. But how we related to the other has to do first of all with how we sort out who we are, and how we understand our own Christian faith in its basics.

This comes to mind on this feast of the Epiphany, a key feast of the year and day for reflection on the universal message of Christ, that he has also come for Gentiles like me and (I suspect) most of my readers: Christ for the nations. But when we start to think about what this means in 2013, I suspect that we soon find that we’ve not thought it through very deeply; and so this is an occasion to ask ourselves what today’s Gospel, Matthew 2, teaches us by what it says and what it doesn’t say:

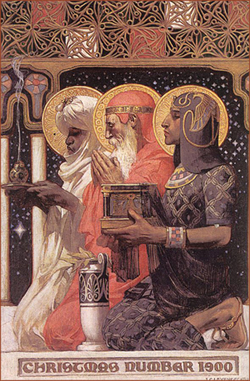

In the time of King Herod, after Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea, wise men from the East came to Jerusalem, asking, “Where is the child who has been born king of the Jews? For we observed his star at its rising, and have come to pay him homage.” …Then he sent them to Bethlehem, saying, “Go and search diligently for the child; and when you have found him, bring me word so that I may also go and pay him homage.” When they had heard the king, they set out; and there, ahead of them, went the star that they had seen at its rising, until it stopped over the place where the child was. When they saw that the star had stopped, they were overwhelmed with joy. On entering the house, they saw the child with Mary his mother; and they knelt down and paid him homage. Then, opening their treasure-chests, they offered him gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh. And having been warned in a dream not to return to Herod, they left for their own country by another road.(Matthew 2.1-12)

While we cannot take this passage alone, as if it is all Matthew wrote, and while we need to read it in light of the rest of the Gospel, and within the tradition of the Church, it is fair also to say that we still need to read it carefully, before blending it in with everything else; only if we take every text seriously will be get anything with the larger picture. So allow me rather briefly to highlight what this passage does not say, and then what it does say. What it does not do is dramatically or melodramatically demonize the night and the dark as if these are evils against which the light shines. This is not the night into which Judas flees in order to betray Jesus, nor the Prologue to John, where darkness fails to overwhelm the light. Rather, in Matthew, night is a time for shepherds and starts, a natural counterpart to day. Day and night are not enemies. Nor is there any dark and evil world surrounding Bethlehem — except, ironically, for those most certainly illuminated, bright cites of Jerusalem (Herod’s domain) and Rome (the center of imperial power). Those are evil, but not the night.

Nor does Matthew give us any hint that the magi are merely astrologers or merely magicians, necessarily or newly ashamed of their craft. In fact, it is their reading of the stars that enables them to find Jesus. Nor do they repent, convert, deny their past. They come to Bethlehem and they worship, and then they return home. That is all Matthew tells us. Presumably they still read the stars, even after the trip. There are of course Patristic traditions — from Gregory Nazianzen and others — that speak of the magi abandoning their astrology and the reading of stars after visiting Bethlehem, as it were becoming proto-Christians. Perhaps, but Matthew tells us nothing about that. We are begin told that we need to be simpler in our expectations about the changes encounter with Christ will bring: perhaps people will be better, brighter, and happier, but after it all, still not members of the Church. They are magi before and after the visit.

The other side of the reading is what it might tell us about how we, followers of Christ, are to act, or be, in light of this feast of the Epiphany. First, it is remarkable how unrelated circumstances work to the good. On the one hand, the stars are in order, and a special star stands out; on the other, Caesar, craving money to support his violent empire, commands a universal census. And so the star is above Bethlehem, and Mary and Joseph are more or less compelled by Rome to go there. Yet in this unexpected way, heaven and earth are in harmony, and the stars and Caesar merely a backdrop for Mary and Joseph, the child and the magi. We are being reminded not to be too cynical about what is possible in our world: sometimes God’s greater plan makes things work out in ways we do not expect, and heaven and earth converge most improbably.

Second, the main thing Mary and Joseph do when the baby is born, and this Messiah has arrived, is to stay put, there in the stable. They are simply there, being parents to the child, who is asleep. No action required. But the world comes to them. While there are many strands of Christianity that urge us to go forth, preach, bring the light to others, Matthew’s message here is rather simpler: do not put your light under a bushel – and then that light, gentle and simple, will draw people to it. They will come, if there be light in you. Not “do,” but “be.”

Third, when the magi find their way to the stable, how do they know what they have found? It is not a palace, after all. They should have doubts. But they do not take Joseph aside and ask numerous questions, nor do they ask Mary about who the father of the child is. They do not test the baby. Nor did their inquiries to Herod help. Rather, they know they have found their destination, since they rejoice, “overwhelmed with joy,” and in that joy they are able to give their gifts. Joy makes the connection clear; other words and proofs are here at least unnecessary. We could do far worse that make joy the criterion for detecting the good news of Christ born in our midst. When we help people to rejoice, even if they do not join our ranks but return home just as before, we will still have made manifest the Good News.

Such is a reading of Matthew 2, and the attitudes we need if we are to really take to heart the message of the Epiphany. If we do, this will help us in dialogue with our neighbors who are not Christians before or after the dialogue. They are not our enemies or competitors, nor our opposites, nor targets for action. They may remain in their own religions after their true and direct encounter with Christ, guided to him by the crafts of their own faith. We will have done our part if in such encounters we are full of light, radiant with Christ, enabling joy rather than demanding conversion.

Matthew has many other things to say, to be sure, but this is enough to get us going in 2013.

FX Clooney, SJ