When Robert Mosher, Richard Bracken, Edward Reid and William Cattano drove onto the campus of the Maryknoll Fathers and Brothers in Ossining, N.Y., on the foggy morning of March 9, 1964, they might not have noticed anything amiss. Men in cassocks were strolling about the property, and everything looked much the same as on their previous three visits to the campus. Perhaps the only incongruous elements were the signs posted here and there reading “Cave Fures.”

Every Maryknoller, from the oldest priests and sisters to the youngest brothers and novices, probably would have known immediately what the signs said. It is not clear, however, that the eager, would-be thieves were well versed in Latin, so it was likely all Greek to them.

The signs read “Beware of Bandits.”

It is not clear that the would-be thieves were well versed in Latin, so it was likely all Greek to them. The signs read “Beware of Bandits.”

The Plan

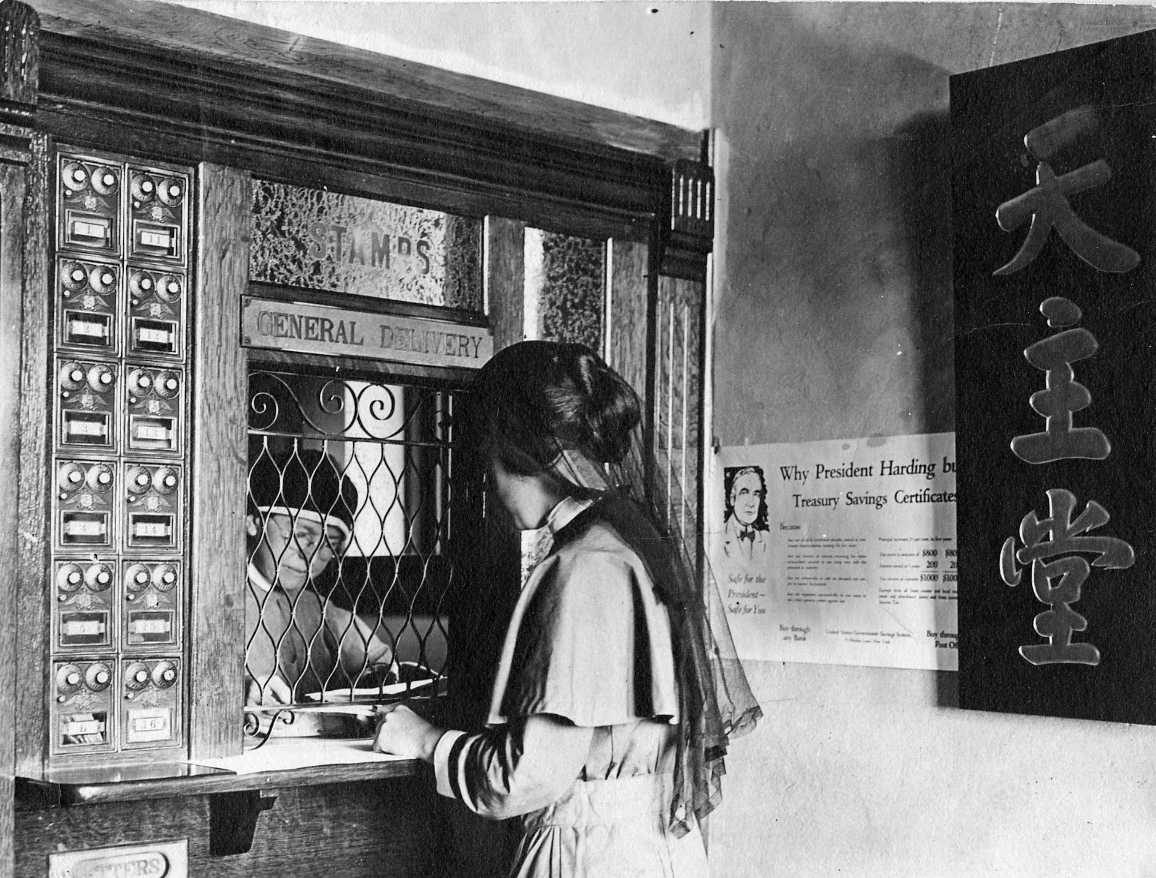

Pulling up in a single rented car to the small post office located in the Price Building on the Maryknoll campus, three of the men raced inside, guns drawn, while a fourth stood outside as the lookout. “It was a terribly foggy day, and so hard to see anything,” Maryknoll priest Father Richard Albertine, who was a seminarian at Maryknoll at the time, remembered recently. “A perfect day for a robbery.”

The bandits quickly forced the postmistress, a woman wearing the habit of the Maryknoll Sisters of St. Dominic (whose campus is directly across the street in Ossining), into a nearby closet. Their goal was to grab cash, postage stamps and the sweetest plum of all: thousands of blank money orders and Treasury Department checks that could be filled out for almost any amount. They loaded mail bags with the money orders and Treasury checks, as well as $3,000 in cash, $30,000 in stamps and, for good measure, incoming mail containing $1,500 in subscription payments to Maryknoll’s magazine and donations to the order.

Suddenly a number of the men in cassocks produced Tommy guns and pistols, and a man with a loud bullhorn ordered the four to surrender.

Their next goal, according to a letter by Albert J. Nevins, M.M., in the Maryknoll Mission Archives (Nevins was director of public relations at Maryknoll at the time, and later served as editor in chief of Our Sunday Visitor for 11 years), was to “then go directly to Mount Mercy College [almost certainly Mercy College in nearby Dobbs Ferry] and rob that of all its tuition monies, and then commit a third robbery on a large parish church in the Bronx, which would not have yet banked its Sunday collection.” (The Church of the Good Shepherd, the bandits’ true third intended target, is actually located in the Inwood neighborhood of Manhattan.)

Emerging a few minutes later, they stashed the mail bags in the trunk of their car and prepared to make their getaway. But not all was as it seemed: Suddenly a number of the men in cassocks produced Tommy guns and pistols, and a man with a loud bullhorn ordered the four to surrender.

The robed men were, in fact, officers of the law—present in huge numbers.

The New York Times reported the next day that 40 state troopers, eight New York City police officers and a handful of Westchester County deputy sheriffs were there to meet the four, and letters in the Maryknoll Mission Archives indicate that both law enforcement and Maryknoll’s leadership had known of the plot for six months.

Father Albertine remembers walking into the garage area of one of Maryknoll’s buildings several hours before the attempted robbery that morning and seeing countless Tommy guns and other weapons, as well as numerous officers. “I got in and out of there as fast I could,” he said. “Actually, they pretty much threw me out!” Meanwhile, the lay employees on the expansive campus had been invited to spend several hours watching movies and enjoying hospitality with doughnuts and coffee in the basement of the Seminary Building.

The Maryknoll sister the thieves locked in the closet? She was Frances Anderson, another Westchester County deputy sheriff. The regular postmistress, Maryknoll Sister William Karen (Margaret) Fitzgerald, had been given the week off. “The decision was made that a police woman would pose as a Sister and would be on duty...” wrote Maryknoll Sister Eileen Mary Moore in an unpublished memoir. “Well, she needed a religious habit and at our convent we were told about the upcoming incident and since I seemed to be about the same size, I was asked to provide a set of my clothing to the police woman.”

The Maryknoll sister the thieves locked in the closet? She was a deputy sheriff. The regular postmistress, Maryknoll Sister William Karen (Margaret) Fitzgerald, had been given the week off.

Why Maryknoll?

To understand why the bandits would target the tiny post office at Maryknoll requires some historical background on Maryknoll and the Catholic Church in the United States in 1964. Vocations to religious life were at an all-time high, and Maryknoll (founded in 1911 with the official name Catholic Foreign Mission Society of the United States) was growing into a vast enterprise, widely admired by American Catholics for the heroic service of its male and female missionaries. Many of the large number of Maryknoll missionaries in China had suffered terribly at the hands of the communist regime in the years after 1949. The New York Times estimated in 1964 that the two campuses of Maryknoll in Ossining were home to 750 priests, sisters, postulants, novices and brothers.

Their magazine, The Field Afar (since rebranded as Maryknoll Magazine and Revista—the latter currently the largest Spanish-language Catholic magazine in the United States), was hugely popular for its firsthand stories of missionary work overseas and brought in large sums in subscriptions and donations—all of them flowing in and out of the Maryknoll Post Office. “It made some sense,” Sister Moore later wrote about the attempted robbery. “American Catholics were incredibly generous. Donations poured in every day through bags of mail.”

A contract bid from a trucking company in 1937 to the superintendent of the U.S. Post Office said that once a month “approximately 1,000 bags of mail containing magazines must be hauled to Ossining and sorted in the Mail Car.” The proprietor complained that it “requires the labor of 4 extra men for eight hours on that day each month.” Just three years later, a Maryknoll employee estimated the number had grown to 2,037 sacks of mail, weighing over 45,000 pounds. Eventually the volume of mail coming and going from the post office led to Maryknoll getting its own zip code. Even today, Maryknoll Magazine and Revista have a readership of over 300,000.

In addition, because of its location at one of the highest points in Ossining and its distinctive and imposing Seminary Building—built of local fieldstone with pagoda roofs in a style that hinted at Maryknoll’s ambitious goals for the conversion of China in the first half of the 20th century—the Maryknoll Fathers and Brothers’ campus was held in some esteem by locals, including those locked up in the nearby Sing Sing Correctional Facility. The Maryknoll building remains the largest standing fieldstone structure in the United States.

Maryknoll also offered an almost perfect layout for such a caper. Woods dominated much of the land on every side, and neither the Maryknoll Post Office nor the larger campus had any security guards—and the post office was located at some distance from the Seminary Building.

A trucking company in 1937 estimated that once a month “approximately 1,000 bags of mail containing magazines must be hauled to Ossining and sorted in the Mail Car.”

The Shootout

In response to repeated calls to surrender, the robbers refused and instead opened fire on the officers while piling into their getaway car. Joseph Healey, a Maryknoll priest now serving in Nairobi, Kenya, was a Maryknoll seminarian living at Maryknoll at the time. He was in class when shots rang out, but told America in an email interview that the priest teaching the class “would not let us go look.”

Three of the robbers were soon shot as they tried to escape in their car. The police concentrated fire on their tires, and their car careened into a ditch; all three were quickly captured. The fourth would-be thief, the lookout Mr. Cattano, sprinted for a side door in the Price Building. According to Jack Jennings, a former New York City detective, in his book Injustice: For the Love of Her Father, detectives hiding inside the door pulled Mr. Cattano into the Price Building, while Jennings tried to cover the door from the outside. He was shot in the hand—the only officer to be wounded in the shootout. Police reports in the aftermath falsely claimed that Mr. Cattano, whom they described as an “unknown fourth man,” had escaped into the nearby woods.

Maryknoll had made plans for the possibility of injury or death. Mary Mercy Hirschboeck, a Maryknoll sister trained as a physician, treated the wounded bandits, while Father Nevins gave Mr. Reid, one of the thieves, absolution, because at the time Mr. Reid’s wounds seemed life-threatening.

“It seemed to me the man was near death,” Father Nevins told a reporter. “I didn’t even see where the man had been wounded...he seemed to be bleeding from everywhere.”

“It seemed to me the man was near death,” Father Nevins told a reporter from the Tarrytown Daily News. “I didn’t even see where the man had been wounded...he seemed to be bleeding from everywhere.”

Upon hearing the news of the failed robbery on the radio, many listeners were confused. Why would a seminary have a post office? Had they just heard correctly that Maryknoll seminarians had robbed a post office? Many tall tales grew from the incident, and suddenly the previously little-known post office was famous. Father Albertine reported that years later he was in Cuba for a meeting with Cuban government officials about missionary work, and one of them said, “Ah, Maryknoll! You have a post office there!”

For the print press, the story was a headline writer’s dream. Life magazine ran a story titled “This is a stickup, Sister.” “Seminary Holdup Foiled by Police,” The New York Times reported. “HOLDUP BATTLE AT MARYKNOLL,” screamed the Daily News in a headline that took up almost the entire front page, with a subhead worth a month’s pay: “3 Thugs Shot in Police Trap.” “Gun Battle Rocks Famed Maryknoll,” chimed in The New York Journal-American. Even the Catholic press joined in: “4 wrong-way robbers muff Maryknoll caper,” reported the Catholic Universe Bulletin, the official organ of the Diocese of Cleveland.

“I suppose you heard about the big holdup,” wrote Father Nevins to another Maryknoller shortly after. “It was planned for last September, was postponed several times and finally came off last Monday while everyone watched from windows and some fifty policemen closed in on the three bandits. The whole thing was quite ridiculous, and if it was made into a television show, no one would believe it!”

For the print press, the story was a headline writer’s dream. Life magazine ran a story titled “This is a stickup, Sister.”

Not everyone was pleased. One man wrote to Father Nevins:

It doesn’t seem believable that a Christian institution and an enlightened police force would have been parties to such a cops and robber game. It should go without saying that the purpose of Christian institutions is to help persons along the way of right, and that the duty of the police is to prevent crime and violence.... How simple and effective it would have been to have taken the robbers (not yet become) and shown them how well the police knew about the robbery plan, and how well-prepared the police were to cope with it.

Father Nevins wrote him a long response, explaining that the police were adamant that the men would simply strike elsewhere if allowed to go free on the Maryknoll caper, and that they were all four known to be violent criminals who would stop at nothing.

How the Caper Was Foiled

Foiling the robbery was not as hard as it seemed. Mr. Cattano turned out to be a snitch and had apparently informed Mr. Jennings, the detective, months earlier of the plan hatched in the cells of Sing Sing after he had been arrested following an earlier robbery. Mr. Jennings notified the F.B.I., the N.Y.P.D. and the Westchester County sheriffs of the plot. He also contacted the superiors of the Maryknoll Fathers and Brothers and the Maryknoll Sisters across the street.

He received permission from the Westchester County Jail, where Mr. Cattano was being held on an assault charge, to take Mr. Cattano out of custody for one night, accompanied by a deputy sheriff and one of Mr. Jennings’ detectives, so that Mr. Cattano could show the officers the route to the post office and the plans for making their getaway. Afterward, the three stopped at a bar for a drink, and Mr. Cattano promptly slipped away into the night, only to be recaptured at 3 a.m. at the White Plains Metro North station; he was returning from a visit to his girlfriend in the Bronx.

The day of the robbery, Mr. Cattano was rushed away from the crime scene for fear he would either be killed by an officer or detected as a rat by the other thieves. The relationship between Mr. Jennings and Mr. Cattano, however, was not the only source of information about the heist. A Maryknoll priest who visited Sing Sing as a chaplain had reported to his superiors that the four men were not the most discreet about their plot, and many a prisoner wanted to know: “Has the Maryknoll Post Office robbery come off yet?”

John P. Martin, a Maryknoll priest who was also a seminarian at the time, recalled seeing “the ‘seminarians’ walking the paths north of the Seminary Building, since my room faced north from over the sacristy. My attention was caught by the fact that they walked around with their hands in their pockets. I knew that they were cops handling their Tommy guns or revolvers and not good seminarians.”

Fr. John P. Martin, M.M.: "My attention was caught by the fact that they walked around with their hands in their pockets. I knew that they were cops handling their Tommy guns or revolvers and not good seminarians."

The Aftermath

The three captured thieves were transported to Grasslands Hospital (replaced in 1977 by Westchester Medical Center) and treated for their wounds. A week later, they were indicted by a Westchester County grand jury for robbery, grand larceny, possession of firearms and assault. All three were sentenced to long prison terms.

The fate of the supposed “unknown fourth man,” Mr. Cattano, remained a mystery to many for 41 years, until J. Radley Herold, a Westchester County assistant district attorney at the time of the robbery, wrote a letter to The New York Times in 2005. “Months before the robbery, the ‘fourth’ man (who has long since died) had informed law enforcement officials of the plan to rob the post office,” Mr. Herold wrote. “According to plan and with the cooperation of the police, he joined the other three men for the robbery and then fled the scene.”

The thieves and their families had figured it out much quicker. According to a 1967 Life magazine profile of Mr. Cattano, “Within minutes of the first radio bulletin on the Maryknoll job, wives and girlfriends of the bandits were on the telephone, hysterically and furiously telling one another that ‘the one who got away had to be [an informant].’” Mr. Cattano, who served time in Rikers Island for his crimes, knew there was a price on his head. “I don’t expect to get to be an old man,” he told Life. By then he had moved to Miami, where the next year he was killed in a suspicious boating accident while consorting with jewel thieves and plotting another audacious heist.

Mr. Jennings, the detective who first flipped Mr. Cattano, was awarded the Journal-American’s Public Protector award for the month of March 1964 and also received a letter of thanks from Cardinal Francis Spellman, archbishop of New York, for his work of “more than seven months to insure the safety of the Church.”

The Maryknoll post office remains open today in its same location. Locals treasure it because there is never a line, and they have been known to protest reports that publicize its existence because of its current efficiency and anonymity. There are no longer sisters (fake or real) behind the counter, nor ersatz priests with Tommy guns roaming around outside, but the campus now has tight security. It is one of the best places in Westchester to mail a letter.

Oh, and Sr. Eileen Mary Moore, who lent out her clothes? “I got my habit back, cleaned, and no bullet holes.”