I cried the first time I went to a traditional Latin Mass.

It would have been difficult for me not to; I was an emotionally volatile 20-year-old college kid studying theology who loved the “smells and bells” that Catholicism offered—and man, there were a lot of bells and smells going on while Mozart’s “Requiem” carried the liturgy.

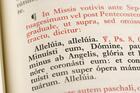

After that, I was hooked. A group of friends and I asked a Jesuit, the late Robert Araujo, if he would learn how to say Mass in the extraordinary form (how the pre-Vatican II traditional liturgy has been known since 2007) so we could have it on campus. He did, and a few of us were trained on how to be altar servers for it. To what I imagine was the shock and dismay of many of his brother Jesuits, we were able to celebrate the traditional Latin Mass at the Jesuit residence. To this day, one of my most-treasured books is a St. Edmund Campion Missal & Hymnal for the Traditional Latin Mass that Father Araujo gifted me.

The traditional Latin Mass (I will refer to it after this as “the Latin Mass” for simplicity’s sake, though of course the current Mass promulgated after Vatican II can be and is also celebrated in Latin) ) never became the primary form of liturgy that I attended, and eventually I stopped going to it altogether sometime after college. But it nevertheless made a significant impact on my spiritual life at a critical, impressionable point in my formation.

[Related: What is the history of the Latin Mass?]

With the news that Pope Francis has greatly restricted the celebration of the Traditional Latin Mass, I have been reflecting on what the Latin Mass gave me and my spiritual life, good and bad.

First, the good: What I saw in the Latin Mass was an unparalleled reverence for the sacred. It hammered home, for the first time, that I was part of a celebration of “these sacred mysteries.” Whereas previously I had attended a lot of parishes that couldn’t bother to get their sound systems working, or that were reliant upon the whimsical improvisations of a well-meaning priest, the Latin Mass was choreographed with the care and attention to detail of a Broadway performance. This care for detail, far from seeming stuffy, instead conveyed a deep and passionate love for what was holy. And even more importantly, it invited me to join in that love by taking similar care in my own prayer and participation in the Mass.

It gave me a hunger for “the beautiful,” despite my eurocentric understanding of beauty. There were no felt banners or tacky papier-mâché art in sight. To that point, when the Met Gala chose “Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination” as its theme, do you think they were looking to 1970s Catholic aesthetics for inspiration?

But do you know what else the Latin Mass did for me?

I cried the first time I went to a traditional Latin Mass.

It made me bitter and arrogant. It made me think I had the more ancient, therefore holier, therefore better way to practice my faith. I would make jokes about the “Novus Ordo” and speculate about the day the church might even do away with vernacular liturgy, considering it a failed experiment. In one example I find particularly galling and embarrassing, when I attended my regular, non-Latin Mass, instead of praying the liturgy I would actually sit there and count all the deviations from the rubrics that I could notice.

I found a lot of security in the (very flawed) idea that “Catholicism is an ancient, unchanging faith. This is the most ancient, unchanging way to live it out.” It took me some time and prodding and prayer to realize that this security wasn’t in or from God, but rather about reassuring myself that I had an answer that I would never need to change (a very attractive prospect to someone whose world feels in constant flux!).

We are called to faith that the truth revealed by God in Christ is eternal and unchanging, but as Pope Francis has pointed out repeatedly (like a good Jesuit spiritual director), rigidity and possessiveness about how to express that truth are not authentically free expressions of faith.

One of the beautiful parts about the celebration of Mass is that it links us to the communion of the church, extending across both time and space. And the Tridentine Mass, representing more than 400 years of that celebration across history, conveys some aspects of that communion powerfully. But unfortunately, some uses of it in our time have become a point of rupture in that communion as well.

The Latin Mass made me bitter and arrogant. It made me think I had the more ancient, therefore holier, therefore better way to practice my faith.

A more widespread celebration of the Traditional Latin Mass was an initiative that “intended to recover the unity of an ecclesial body with diverse liturgical sensibilities,” Pope Francis explained in his letter explaining his motivations for the motu proprio “Traditionis Custodes.” However, in effect it “was exploited to widen the gaps, reinforce the divergences, and encourage disagreements that injure the Church, block her path, and expose her to the peril of division.” When I read those words, I knew it was true in my own personal spiritual life. It is a great sadness that it was exploited. And if the pope and the bishops around the world who responded to his questionnaire on this topic saw this division throughout the church, Francis was right to respond.

But, you may object: I am not a smug pseudo-schismatic who hates the pope, and I love the Latin Mass! Here is the difficult thing being asked of you by the Holy Father: There are many good reasons to love the Latin Mass, but given that it has become a demonstrable cause of disunity and rancor within the church, we have to look for the gifts it gives elsewhere.

Pope Francis readily admits that he agrees with Pope Benedict XVI that “in many places the prescriptions of the new Missal are not observed in celebration, but indeed come to be interpreted as an authorization for or even a requirement of creativity, which leads to almost unbearable distortions.” So, one task at hand, and a possible place of common ground for divided Catholics, is to focus on making regular Masses a bit more reverent. After all, the good things that I received from my encounter with the Traditional Latin Mass should have been available to me in the Novus Ordo, too. All good liturgy, in whatever form or language, should engender desires for the good, the true and the beautiful.

But there is another, deeper and more difficult spiritual challenge here. The desires that the liturgy awakes and satisfies in us—and for some of us, the desires that the Latin Mass especially nurtured—are good, holy and necessary. But those desires also point beyond the liturgy itself. At the risk of sounding glib, what would it mean if we could find the spiritual goods that the Latin Mass taught so many in other places? What if we were able to discover a passion for beauty from our service to the poor? If we could develop a mature sense of wonder and awe from caring for creation, our common home?

If I am honest, those feel like daunting questions that I don’t really know how to respond to. I only know that I think I’m being called to ask them. Answering them, I imagine, will take patience, practice and a lot of prayers—in whatever language they’re said.

[Read this next: Explainer: What is the history of the Latin Mass?]