A Reflection for Monday of the Thirtieth Week in Ordinary Time

Find today’s readings here.

As a Catholic who believes in the healing power of God, I want to love today’s Gospel. As a sister, I’m conflicted.

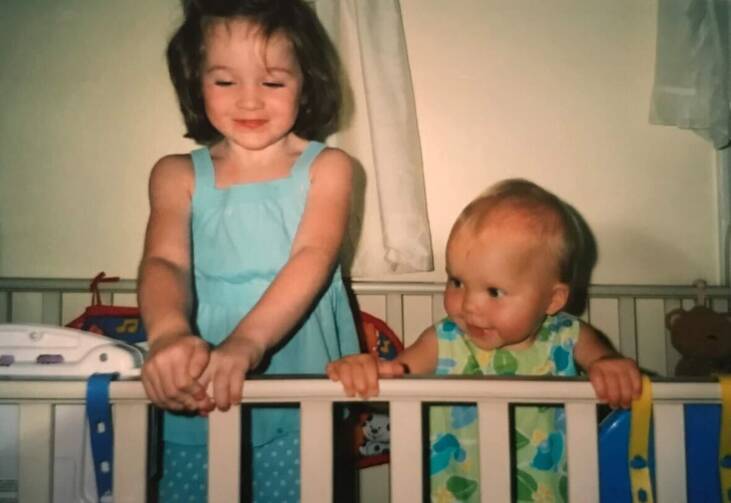

My little sister, Charlotte, was born with a genetic abnormality that manifests in moderate to severe developmental disabilities. I became acquainted with my faith alongside her while attending Mass as a family; my image of God is inextricably bound up in my relationship with my sister.

It’s often difficult for parents of young children in church, but I’m filled with a particular reverence for my parents when I think back to those years when Charlotte might have appeared a little too old to have a meltdown in Mass. I think about my snotty, 12-year-old self squirming in the pew, desperate for my parents to take Charlotte to the back of the church—not so I could pray undisturbed, but to preserve my own ego from the wandering eyes of the other parishioners. I used to worry that someone would say something to us, not understanding. Now, I worry that these voices were inside of me all along, confusing holiness with propriety.

Much like the hypocrites who criticize Jesus for healing on the Sabbath, I thought that being holy meant following the rules, but today’s Gospel reminds us that saintliness is in the seeking. Each Sunday, my parents sat our family in the third-to-last pew of the side section of our church so that they could step out with Charlotte if necessary. If she did have a meltdown, one of them would stand outside with her until she calmed down, even if the timing meant that they were unable to receive the Eucharist. Every week throughout our childhood, my parents accepted the risk of bearing that anxiety and frustration because they wanted to share their faith with their children. Even when it was messy, it was always holy.

Charlotte’s disability makes it much more difficult for her to move through the world, and though I would do anything to alleviate that suffering, I would not wish for God to “heal” her of her disability.

But of course, all of this is in response to the healing itself, which I have a much harder time with.

Charlotte’s disability makes it much more difficult for her to move through the world, and though I would do anything to alleviate that suffering, I would not wish for God to “heal” her of her disability. It’s an integral part of what’s made her the extroverted, funny, Taylor-Swift-obsessed 20-year-old I love. To borrow the words of Greg Boyle, S.J., I believe deep in my bones that she is “exactly what God had in mind when God made [her].”

In 2017, America ran a piece by Heather Kirn Lanier entitled “My daughter has a disability. I don’t want Jesus to ‘fix’ her.” In it, she argues that healing stories, like the one in today’s Gospel, can “[reinforce] the idea that the disabled body is broken, damaged” and “treat the disabled body as something to fix.” When I read how today’s Gospel attributes the woman’s disability to the bonds of Satan, I cannot escape the pit in my stomach. Why is it that God’s glory is revealed only when she stands erect, while I see that glory made apparent in my sister every day, disabilities and all?

But then I think of the first reading from Romans, which proclaims that “we are not debtors to the flesh” and are freed by the Spirit, and I am reminded that God’s ways are not our own. We are not to live according to the flesh, so why should we think of healing in only this narrow, fleshy way? Both of these things can be true: I believe in a God sent to heal the world’s brokenness, and I believe that same God made my sister exactly as she is.

I have never seen a healing in the way this Gospel portrays it, but I have heard Charlotte say that Jesus loves her. She cannot read the Gospel or tell you much about Jesus’ life, but she knows that to be true. What is healing, if not radically affirming the dignity of a person such that she can inhabit that truth—that no matter what our fleshy, narrow-minded world says about ability and worth, she is beloved. She is whole. She is holy.