An icon of the Madonna and Child was stolen from Catholic University in 2021; the university responded by installing a second print of the image, which depicted both Jesus and Mary as Black. The second print was also stolen.

During the Amazon Synod in Rome in 2019, an Indigenous woman from the Amazon region presented a wooden carving of a pregnant woman to Pope Francis that she called “Our Lady of the Amazon.” Soon after, self-appointed guardians of orthodoxy who claimed the folk art depicted a pagan goddess stole it from a Roman church and threw it into the Tiber River.

And just last week, an eight-foot icon depicting Christ as a Mescalero Apache holy man by the artist Robert Lentz, O.F.M., that has hung beneath the crucifix in a Franciscan church in New Mexico for 45 years disappeared overnight. According to parishioners, diocesan officers have admitted the icon was not stolen by strangers: The pastor of the church—with the help of some Knights of Columbus—removed the icon himself, and the diocese won’t tell them where it is.

What do all these incidents have in common? The first two are examples of sacrilege—the violation or improper treatment of a sacred object—which is something of an irony given that many champions of such thefts usually claim to be defenders of the Catholic faith. And all three are examples of resistance to inculturation, part of the process by which the faith becomes rooted in disparate cultures—and those cultures offer their own gifts in return—while preserving the unity of the universal communion of the church and the integrity of the Gospel message. That is not a scholar’s definition, mind you, but it’s the jist of it.

What is inculturation?

Processes of inculturation have taken place throughout the church in every place and time, and the phenomenon isn’t new. Remember St. Paul telling the Athenians in Acts 17: 23-31 that their shrine to “the unknown god” was actually a shrine to the one true God whose message he was there to preach? That is a kind of inculturation. I recognize this part of your culture, St. Paul says, and value it because it expresses part of the truth of the Gospel message.

Remember the early church leaders deciding that Christian converts didn’t need to follow Jewish dietary laws and be circumcised? That’s part of a process of inculturation too. Our rules, the early church decides, require nuance and alteration in light of the new cultural realities we are encountering.

Oh, and the Traditional Latin Mass, said for centuries in a language Jesus didn’t use and that the apostles couldn’t speak? That is classic inculturation—the kergyma expressed in the local language for purposes of evangelization, and the local church (Latin Christendom in that case) contributing its cultural gifts to the church’s worship tradition. So, too, is our contemporary use of vernacular languages in the liturgy part of a process of inculturation. The teaching and message of the missionary church are preserved, but in cultural forms that make it intelligible to believers.

The exchange goes both ways: The universal church is always being built up by specific gifts of the cultures in which it takes root. (It’s not just Mexican Catholics anymore who revere Our Lady of Guadalupe, after all.) This process was already taking place in early Christianity’s acceptance of the terms of Greek philosophy (in the Council of Chalcedon, for example), as the bishops at the Second Vatican Council made clear in “Gaudium et Spes”:

For, from the beginning of her history she has learned to express the message of Christ with the help of the ideas and terminology of various philosophers, and has tried to clarify it with their wisdom, too. Her purpose has been to adapt the Gospel to the grasp of all as well as to the needs of the learned, insofar as such was appropriate. Indeed this accommodated preaching of the revealed word ought to remain the law of all evangelization. For thus the ability to express Christ’s message in its own way is developed in each nation, and at the same time there is fostered a living exchange between the Church and the diverse cultures of people.

Theologians have even proposed that the gifts of the Magi in the Gospel of Matthew can be rightly considered the first example (and perhaps a model) of inculturation: Intrigued and inspired by the Good News they have received, the Magi offer the gifts of their own traditions to the Holy Family, and at the same time become an integral part of the Good News themselves.

Recent history

Despite its presence throughout church history, “inculturation” as a term didn’t start showing up in official Vatican documents until the papacy of John Paul II, who used the term early and often in both official documents and informal settings. During his papacy, the Pontifical Biblical Commission released a 1988 document titled “Faith and Inculturation” that included the following assertion:

Relying on the conviction that “the incarnation of the Word was also a cultural incarnation,” the pope affirms that cultures, analogically comparable to the humanity of Christ in whatever good they possess, may play a positive role of mediation in the expression and extension of the Christian faith.

Of course, in the academic fields of missiology and ecclesiology as well as in pastoral practice, a recognition of the importance of inculturation has long since become a sine qua non of any competent understanding of the church or its mission. Whether through language, art, music, modes of understanding leadership or even the cultural sensibilities of a people, the Gospel does not spread without rooting itself in culture and being bolstered by culture in turn. Further, many missiologists will tell you that what was perceived as syncretism in previous eras can in many cases actually be considered valid inculturation and evangelization.

Check out what Pope Benedict XVI had to say about Sts. Cyril and Methodius, the famous “Apostles to the Slavs”:

Cyril and Methodius are in fact a classic example of what today is meant by the term “inculturation”: every people must integrate the message revealed into its own culture and express its saving truth in its own language.

The public declarations of both John Paul II and Benedict XVI on inculturation also largely developed out of Pope Paul VI’s monumental 1975 apostolic exhortation, “Evangelii Nuntiandi,” on the nature and purpose of evangelization. Pope Paul VI made the following point about how the Gospel is spread:

The Gospel, and therefore evangelization, are certainly not identical with culture, and they are independent in regard to all cultures. Nevertheless, the kingdom which the Gospel proclaims is lived by men who are profoundly linked to a culture, and the building up of the kingdom cannot avoid borrowing the elements of human culture or cultures. [Emphasis mine]. Though independent of cultures, the Gospel and evangelization are not necessarily incompatible with them; rather they are capable of permeating them all without becoming subject to any one of them.

White Americans and Europeans should understand more than anyone the danger of pretending there is only one way to portray Catholic truths. After all, for centuries on end we have been exposed to pictures of Jesus as a white man—sometimes as a blue-eyed, blond white man. Depicting the Holy Family instead as Chinese, as Black or as Latino is no different: It is a culture’s way of making a connection with its savior and its salvation, and one cannot object on the grounds that Jesus and his mother no longer look like us. And to steal or destroy another culture’s attempts to make that connection is no heroic act. It is simply bigotry.

Pope Francis has been clear on this point. In Without Jesus We Can Do Nothing, a book written by the Italian journalist Gianni Valente and based on interviews done during the Amazon synod, the pope said that there are “circles and sectors that present themselves as ilustrados (enlightened)—they sequester the proclamation of the gospel through a distorted reasoning that divides the world between ‘civilized’ and ‘barbaric.’”

Such people, he wrote, “consider a large part of the human family as a lower-class entity, unable to achieve decent levels in spiritual and intellectual life. On this basis, contempt can develop for people considered to be second rate.”

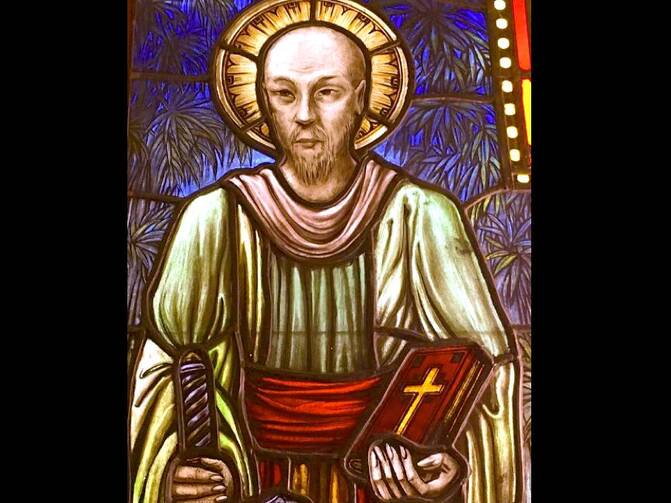

I worked for many years at the Maryknoll Society Center in Maryknoll, N.Y., where several generations of missionaries had come to Maryknoll from all around the United States and then had gone forth “ad gentes,” to the nations of the world. In an alcove at Maryknoll are stained-glass images of Sts. Peter and St. Paul (the latter in the picture above). Both saints are depicted as Chinese. They don’t look like me. Of course, neither did the real St. Peter or St. Paul. Culture still gives us the tools with which to connect with them across the centuries, in every place and time.