How did you happen to go to Cambodia?

I left the United States in 1979 to work as a physician’s assistant with Jesuit Refugee Services in camps on the Thailand-Cambodia border; it was the time of the Khmer Rouge slaughter of Cambodians, the so-called killing fields. Initially I was to stay only three to six months, but I ended up staying in the camps for nine years.

I took a year off (in 1988-89) to work as an ordinary rice farmer, living with my adoptive Cambodian family. Soon after, I helped found the Coalition for Peace and Reconciliation, a group of like-minded people focusing on issues of peace and war, which is still functioning. One of our first undertakings was to attend the peace talks in Jakarta, in Indonesia, where we met the Cambodian Buddhist monk Maha Ghosananda. He asked, “Why do you help just one group of my people, refugees, when all Cambodians want peace?”

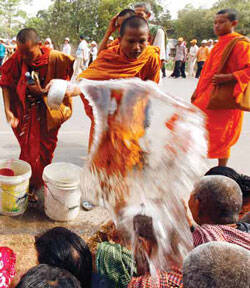

After the peace accords were signed, we accompanied Ghosananda on foot with 100 refugees from the Thai border’s camps to Phnom Penh. That was in 1992, the first of many peace walks he began. The walk, or pilgrimage, is called the Dhammayietra in Cambodian; it goes back to Buddha himself, who walked with his monks and nuns into areas of conflict over 2,500 years ago to witness for peace. Maha used a peace prayer every day: “The suffering of Cambodia has been deep; from this suffering comes great compassion; great compassion makes a peaceful heart; a peaceful heart makes a peaceful person.” The prayer continues with words like family, community, nation and world.

Has your spirituality changed through your close contact with Maha Ghosananda?

My spirituality arises from the pilgrimages. There have been 17 walks now. You almost automatically enter into prayer and meditation as you walk. In a small country like Cambodia, I walk almost everywhere. If somebody offers me a ride, I take it, but otherwise I just walk. I look at life as a long walk, somewhat in the same way that Dorothy Day saw life as a long loneliness, the title of her autobiography. Sometimes the walk is easy; but sometimes, in the cold and the heat, it’s hard.

Mostly I just see myself as a person who tries to listen inwardly. I get up at 3 or 4 a.m. to sit in silence, often writing as I sit, as a form of meditation. In addition to Maha, who died in March 2007, Gandhi has also been a big influence in my life.

Maha used to say that we must leave the safety of our temples and churches and enter the temple of human experience, filled with human suffering. If we really listen to the Buddha, Christ or Gandhi, we can do nothing else but be in refugee camps, prisons, ghettos and battlefields, Maha would say. These have to be our temples. He speaks of this in his book, Step by Step.

What did you do when the war in Cambodia ended?

Many people were suffering and dying from AIDS, so we began a program in Cambodia’s northwest to help them. We also worked in the prisons. The justice system in Cambodia is itself a source of suffering. No one with money is in prison, because you can pay your way out. Although some Cambodians are behind bars because of violent crimes, most are in prison because of what might be called crimes arising from poverty, like stealing. The longest sentence is 15 years; Cambodia has no death penalty.

The basic unmet needs of prisoners are for clean water, adequate food and exercise and family visits. One prison we worked in was built on land without an adequate clean water source. Plus, the sewage system didn’t function properly. As for food, only 25 cents a day was allotted for that. The guards’ pay is minimal, so when visitors come, often after a long journey, they have to give the guards money or be turned away.

That low-pay situation prevails across the board for government workers. A teacher might deliberately teach very fast and say to a student who couldn’t follow, come back at 5 p.m., and I will give you that same lesson for 500 riel (12 cents). Doctors, too, might put in an hour at the public hospital and then go off to their private practice. Everyone has to find a way to survive. They’re often driven to take advantage of one another.

AIDS is an especially difficult situation in prisons because without money to pay the medic, it is not easy to be tested. As a result, prisoners don’t know they are infected until symptoms appear. In prison, once you’re found to be infected, by law you should get free care. But because the prison medics are paid so little, you have to pay them to receive care. Ultimately, the really sick ones are taken to the hospital, where they’re finally given the proper anti-retroviral medications.

My prison work began when I was a translator for the International Committee of the Red Cross. We also started a peacemakers program as part of the Coalition for Peace and Reconciliation: some of the local youth would go into the prisons as volunteers to teach basic literacy skills. You’d have these young people, with all the usual prejudices against prisoners, going into a huge cell with 120 men, about a third of whom couldn’t read or write. In Cambodia, you respect your teachers. So the prisoners who wanted to study would take their student teachers to a corner and the whole cell would stay quiet. The prisoners realized that the young people were volunteers, not paid and not part of a nongovernmental group, which made their respect for them go even higher.

Are landmines still a serious problem there?

A big problem. It is estimated that as many as 10 million were laid during the war years. But mines don’t know when a war is over, so people are still being injured and killed. The mine removal process has helped, but two years ago there was a big jump in the number of injuries and deaths. We found that because China had raised the price of metal, poor farmers would look for unexploded ordnance to get the metal parts they could sell. It was a matter of poor people just trying to survive, but blowing themselves up in the process.

Part of the problem has to do with the land. Increasingly, wealthy people are pushing poor people off their land, so poor people have to move farther out to areas not yet cleared of mines. The growing gap between rich and poor is one of the seeds for a possible future war. You get a sense of the gap when you hear about tourists going to Angkor Wat, Cambodia’s most famous temple. They can fly in from cities around the world, stay at a five-star hotel nearby, then be driven out to the temple complex on new roads. They never realize that on bumpy country roads within a few miles of the temple, people barely have enough to survive.

Are there still signs of the war in Cambodia?

A student there once said to me, “You Americans make great fish ponds.” He meant the craters left by U.S. bombs, which then filled with water. He was too young to know those days himself, but he heard about them from his parents, who remembered the time when the United States bombed the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Cambodia in an effort to end the Vietnam War. The Cambodian peace accords were signed in the early 1990s, but peace didn’t take hold for another decade. Cambodians my age, in their 50s, carry the suffering of the Khmer Rouge period. An organizer of the peace walks once pointed to a man selling bananas in the market and said, “He killed about 20 people in my village in 1977.” We bought fruit from him and joked about the price. People carry the war within them.

When Cambodians realize you’ve been there a long time, they just start talking about the war years and the suffering they endured. Once a young man stopped me and said: “Do you remember me? You fed me ice cream when I was a baby in 1979. I know because my mother saw you walking by, and she told me about the refugee camp where you were working.” I initially worked in an intensive feeding ward, when starving people were escaping from Cambodia into Thailand in 1979. Still another time, a man on a motorcycle stopped me and offered me a ride. Same question: “Remember me? You gave me soap when I was a prisoner in 1994.” “Was it four bars of Lux?” “Yes,” he said. That was when I was working as a translator for the International Committee of the Red Cross—distributing supplies like soap was part of the job.

Before I came back to the United States last fall for a year of visiting peace communities and discerning whether to go back to Cambodia, three young people from our peacemakers program wanted to go back to the site of the refugee camp where they had been born. On Christmas Day 1984, that camp was attacked. One of the young women visiting her birthplace in the camp remembered being picked up as a five-year-old by the back of the neck and flung onto the back of a motorcycle when shelling began. My own memory of that time as a physician’s assistant was of seeing people around me dying. That same Christmas Day, in the midst of the bombing, I delivered a baby.

What will you do if you decide to remain in the United States?

I would hope to use the many years of war experience in Thailand and Cambodia to emphasize what war does to people. That is part of my past experience, and it’s part of me now. I sometimes wonder whether there will be war again in Cambodia. At times, there seem to be more seeds of war being sown than seeds of peace. Maha Ghosananda used to speak of what he called landmines of the heart: greed, hatred and ignorance. These have to be “de-mined” if there is to be lasting peace.

Read the editors take on the Khmer Rouge from 1975.