Years ago in these pages, Richard A. Blake, S.J., crowned Woody Allen as the most outstanding American film director then working in films. He even suggested that some day Allen might be proclaimed the finest American director ever. At the time, the evaluation may have seemed an exaggeration. These days, Blake would have plenty of evidence to support his case.

Allen has written and directed approximately 45 films, and though there was a brief period when he did not quite maintain the level of excellence we had come to expect of him—I am thinking of such films as “The Curse of the Jade Scorpion” (2001), “Hollywood Ending” (2002), “Anything Else” (2003) and “Melinda and Melinda” (2004)—his abundant output includes an impressive number of exceptionally fine films. His best work includes “Annie Hall” (1979), “Manhattan” (1979), “Stardust Memories” (1980), “Zelig” (1983), “The Purple Rose of Cairo” (1985), “Hannah and Her Sisters” (1986), “Radio Days” (1987), “Crimes and Misdemeanors” (1989)—which I consider his masterpiece—“Alice” (1990), “Match Point” (2005) and “Midnight in Paris” (2011), his biggest commercial success. In his latest film, Blue Jasmine, Allen continues to give evidence of his complete mastery of the medium of film while both surprising and delighting the viewer with an imagination that is insightful and fresh.

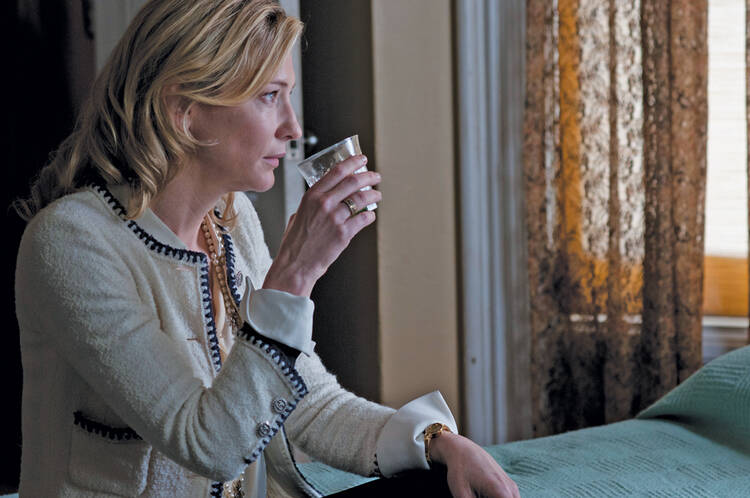

“Blue Jasmine” is bleak but brilliant. The plot is centered around the title character (played by Cate Blanchett), whose personality seems to have no center at all. In the course of the film we learn that she has changed her first name from Jeanette to Jasmine and added the name Blue because when she and her wheeling-and-dealing husband, Hal (Alec Baldwin), first met, Rodgers and Hart’s song “Blue Moon” was playing. Hart’s opening lyrics could be taken as a description of Jasmine and eerily prophetic of her future: “Blue Moon/ You saw me standing alone,/ Without a dream in my heart,/ Without a love of my own.”

We also discover that Jasmine has suffered a total breakdown after learning that her husband has been having multiple affairs and is leaving her to marry a teenage au pair. In a fit of anger, Jasmine, who has always had the ability to disregard anything that does not go along with her self-image or her vision of her future, finally faces her husband’s thievery, and he ends up in jail.

After her breakdown, Jasmine, who has spent her married life mingling with Manhattan millionaires, leaves New York and visits her sister Ginger (Sally Hawkins), who lives in San Francisco in much less affluent surroundings. Adopted from two different sets of parents, the sisters had a sibling rivalry; Jasmine was their adoptive parents’ favorite. Ginger tries to help her deeply wounded sister even though Ginger’s divorce from Augie (Andrew Dice Clay) was precipitated to some extent by Jasmine’s criticism of Ginger’s choice in men and by Hal’s dishonest dealings.

Jasmine has another chance at marriage when she meets Dwight (Peter Sarsgaard), a millionaire diplomat interested in entering politics and in the fact that Jasmine’s good looks and ability to seem at home with those in the wealthiest social class will benefit his career. However, Jasmine’s distorted version of reality thwarts this relationship, too.

Throughout the film Jasmine self-medicates with anti-depressants washed down with vodka. By the end of the movie Jasmine is on the brink of another total breakdown; her rupture with reality has led her into her own solipsistic world.

Both Allen and Blanchett have offered comments on Jasmine’s woundedness. Allen says in the press materials for the film: “[H]er story isn’t just about economic deprivation, it’s about a tragic flaw in her character that made her the instrument of her own demise…. She is someone who chose not to look too deeply at the source of her pleasure, her income, her security, and because of that paid a terrific price.”

Blanchett has said: “We all to a certain degree see what we want to see in the people who we are surrounded by and certainly in ourselves. It’s very, very difficult for a human being to truly look at themselves in the mirror, to truly see who we are, warts and all—and it’s very difficult to change. In the end, Jasmine is a product of all the delusion and evasion that we all have to some degree, but as time has passed she’s become deluded on an epic scale.”

Every member of the cast in “Blue Jasmine” is exceptionally good, but Blanchett is something special. That she is an outstanding actress is obvious in this film.

Allen has made a habit of working with some outstanding actresses, like Meryl Streep, Diane Keaton, Geraldine Page, Mia Farrow, Mira Sorvino, Dianne Wiest and Scarlett Johansson. Four Academy Awards were won by actresses directed by Allen: Diane Keaton (“Annie Hall,” 1977), Mira Sorvino (“Mighty Aphrodite,” 1995) and two by Dianne Wiest (“Hannah and Her Sisters,” 1986, and “Bullets Over Broadway,” 1994).

Allen is known for giving what seems like little direction and for encouraging performers to be creative and even to change lines if they feel uncomfortable with what he has written. Blanchett, who likes to receive suggestions from a director, has said she found Woody’s approach difficult at first, but she has turned in a performance worthy of an Academy Award.

Yet one wonders: If Allen is so laid back in dealing with actors, how does the magic happen? It might be that he has written wonderful parts in which talented actors can shine forth. It also might be that Allen casts his films very carefully, perhaps even having a particular actress in mind when he is writing. It might be part of the mystery of artistic creation that even artists do not fully understand.

Allen’s films are filled with psychological insights, sometimes played for laughs, sometimes played more seriously. There are also provocative insights into morality. As an astute observer of the human condition, Allen, an avowed atheist, remains very sympathetic toward his characters (witness the ending of “Deconstruct-ing Harry,” 1997). Nevertheless, he depicts moral failings honestly. Though in interviews Allen denies that there is an objective morality or anything resembling the natural law, and certainly no divine reward or punishment beyond the grave, his films suggest that there are people who act not only foolishly but immorally, and that true evil exists. I think of Monk (Danny Aiello) in “The Purple Rose of Cairo,” 1985; Judah Rosenthal (Martin Landau) in “Crimes and Misdemeanors,” 1989; Doug Tate (Jonathan Rhys Meyers) in “Match Point,” 2005; and others.

Although Allen may already have won a place in the pantheon of such great American directors as Orson Welles, John Ford, Frank Capra, Howard Hawks and William Wyler, there is no sign that he is resting on his laurels. Word is that Allen is spending this summer in the south of France making his next film.

Read a selection of Father Richard Blake's reviews of Woody Allen's films.