Remembering the Past, Processing to the Future

Though today’s feast almost seems like an appendix to the liturgy of Holy Thursday and solemnizes what we believe in every liturgy, it provides a wonderful overture to the resumption of Ordinary Time. The feast originates in the visions of St. Juliana of Mt. Cornillon (1193-1258) and was celebrated first as a local feast but was extended to the whole church by Pope Urban IV in 1264. It was primarily a processional feast, which quickly spread throughout Christendom. St. Thomas Aquinas composed the Divine Office for the feast. The Eucharist was carried throughout a town or village, and the processions grew into dramatic re-enactments of the whole course of salvation history. The risen Christ, present in the Eucharist and in the church, accompanied people throughout their ordinary lives, and in many parts of the world the feast is still celebrated with traditional rituals involving music and dance. The feast is a classic example of liturgy “from below,” as each culture paints the festival in different hues.

God emerges from the first reading as the leader and companion on a people’s journey. Moses addresses a people about to enter the promised land and summons them “to remember” the saving deeds of God, reminding them that it was by God’s power and love, not their own, that they had been released from slavery. At the same time he warns them of the perils that await if they abandon God’s command. The possession of the land they will enter is contingent on their fidelity to the covenant.

The Pauline selection and the Gospel speak more directly to the themes of the feast. In this section of 1 Corinthians, Paul deals with various disputes among his fractious community over eating food offered to idols and attendance at pagan banquets. In today’s short reading he argues that all sacrifices, Christian (10:1-17), Jewish (v. 18) and pagan (v. 18) establish a form of communion (koinonia) with the God to whom the sacrifice is offered. In sharing the cup of blessing and breaking bread together, Christians celebrate communion with the body of Jesus broken on the cross and his blood poured out for us. This creates the deepest union among Christians—a union that is threatened by participation in pagan banquets. Most likely Paul addresses here people in the community with greater resources and social standing who will also distort the meaning of the Lord’s Supper by shaming the “have nots” (1 Cor. 11:17-26).

Motifs from the Exodus events permeate the Gospel. Throughout John 6, Jesus contrasts the food that he will give to the manna given in the desert. Bread in this chapter has the double sense of wisdom from heaven and the bread of life that is Jesus himself. The stark realism of the language “eat flesh,” “drink blood” emphasizes that the life of the Word made flesh and his death on the cross bring eternal life to the Christian. Eternal life is fullness of life with God in Jesus.

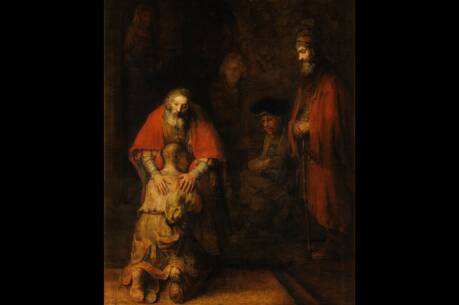

A number of fruitful themes emerge from this feast. The image of a procession of ordinary people following the enshrined host, often carrying symbols of their trade or craft, recalls our procession through life and reminds us that the Eucharist is our food for the everyday journeys of life. These journeys mix the joy of resurrection with sorrow over death, the death of Jesus on the cross. The Eucharist we receive and enshrine is never simply a meal or an object of adoration, but a memorial of a life given for others and a summons to seek the kind of communion with God and others that Paul proclaims. Often in today’s church (well rooted in Corinth), the manner of celebrating the Eucharist is a source of division. Paul does not address this division by taking sides. (Later he will say that he and other Christians who know that idols are folly can eat food offered to them, but should refrain from eating if this presents an obstacle to the weaker brother or sister [1 Cor. 10:23-11:1]). The important thing is union in Christ, not disputes about him.

Historically, the feast also reminds us of the importance of liturgy “from the people.” In our century as in no other, the church has taken root in many diverse cultures. Just as in the Middle Ages devotions and ritual emerged that celebrated how God’s love touched ordinary life, contemporary cultures will add to the rich tapestry of Catholic devotion. Pope Urban IV approved the feast and processions of Corpus Christi, because they expressed the faith and devotion of the people. What wisdom does a 13th-century pope offer today?

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “Remembering the Past, Processing to the Future,” in the May 27, 2002, issue.