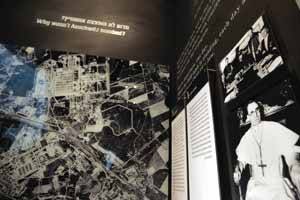

Over the last few months, the question of Pope Pius XII’s conduct during World War II has again made the news. At the recent Synod on the Word of God in Rome, Chief Rabbi Cohen of Haifa said that many Jews still believe certain Catholic leaders did not do enough to prevent the Holocaust. On Oct. 9, the 50th anniversary of Pius XII’s death, Benedict XVI endorsed the beatification of the late pontiff. Meanwhile, Abraham Foxman, the U.S. director of the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith, has called for opening the Vatican archives for the war years to ascertain whether, as Benedict stated in October, Pius actually did work secretly to save many Jews.

In fact, there already exists historical evidence to make certain judgments about Pius XII. Researchers can glean much from the archives for Pope Pius XI that were opened in 2003 and 2006, especially in regard to Eugenio Pacelli, the future pope, as secretary of state. Twelve volumes of wartime documents published between 1967 and 1981, together with other national archives and newspapers, provide an additional basis for assessing Pacelli’s behavior during wartime.

Largely because of his 1937 encyclical condemning the racial policies of the Nazi state (Mit Brennender Sorge), Pius XI has often been praised for his boldness on the eve of war. Pius XII, on the other hand, has been condemned for his relative “silence” in the face of Nazi aggression. Pacelli, critics contend, was so fearful of Communism that he sided with Hitler. Yet a close study of Pacelli’s activities as secretary of state and later as pontiff yields a different picture.

A Diplomat’s Dilemma

Eugenio Pacelli was appointed Vatican secretary of state in 1929. He was the first to hold the position after the signing of the Lateran treaties, which established the Vatican City State in order to guarantee the spiritual sovereignty of the pope. The treaties effectively ended the state of siege that had existed between the Holy See and the Kingdom of Italy since 1870. Pacelli had the task of shaping a new direction for Vatican diplomacy, yet he sometimes looked to past solutions to solve the problems he faced. He, for example, trusted concordats, such as the one he negotiated with Nazi Germany in 1933, to guarantee the legal rights of the church. The Nazis violated the agreement as early as the fall of 1933, and consistent violations led Pius XI to issue Mit Brennender Sorge. A few episodes surrounding the drafting and promulgation of this encyclical illustrate Pacelli’s anti-Nazi sentiment.

In November 1936 Pacelli returned from a monthlong tour of the United States that included a visit with President Franklin D. Roosevelt. In Rome, he found, the conflict between the German church and the Nazi government had worsened. Early in January 1937, Pacelli summoned five leaders of the German hierarchy to a meeting in Rome. The six prelates developed a statement listing grievances against the Nazis and presented it to Pope Pius XI, who then signed it. Because of government restrictions, the nuncio in Berlin, Archbishop Cesare Orsenigo, had the encyclical distributed by courier and read from the pulpits of German Catholic parishes on Palm Sunday 1937. The German police confiscated as many copies as they could and called it “high treason.” In the end, the encyclical had little positive effect, and if anything only exacerbated the crisis. The American ambassador reported that it “had helped the Catholic Church in Germany very little but on the contrary has provoked the Nazi state...to continue its oblique assault upon Catholic institutions.”

The encyclical also occasioned the renewal of show trials against Catholic school teachers for supposed violations of morality. The Concordat of 1933 guaranteed the church’s right to educate, but by bringing these charges against Catholic educators, the Nazis sought to prove that the church itself was in violation of the terms of the agreement.

Cardinal George Mundelein of Chicago made the Nazi attacks on the German church the topic of his address to his clergy in May 1937. He wondered how “a nation of 60,000,000 people, intelligent people...will submit in fear and servitude to an alien, an Austrian paperhanger, and a poor one at that I am told.” The cardinal’s office released the full text to the press, which broadcast it around the world. Upon learning of the speech, Pacelli asked the apostolic delegate to the United States for a copy of the “courageous declaration.” The German ambassador to the Holy See demanded that Mundelein be reprimanded for his attack on the German head of state. Instead, Pacelli, together with the cardinals who comprised the Vatican’s advisory group on foreign relations, stood by Mundelein’s right to freedom of speech in his diocese and informed the German embassy that the problem arose from the Nazi persecution of the church. The Mundelein episode, however, provided the German government with another excuse for further attacks on the church.

Pacelli and the Anschluss

Pacelli’s handling of the case of Cardinal Theodor Innitzer of Vienna is a further illustration of his anti-Nazi feelings. In March 1938 Innitzer embraced the Nazis’ entry into Austria and led the hierarchy in urging Austrian Catholics to vote for the Anschluss. The nuncio to Vienna, Archbishop Gaetano Cicognani, the brother of the apostolic delegate to the American hierarchy, informed the American embassy that the Vatican did not support Innitzer’s position. According to the nuncio, Innitzer had undermined the German bishops in their opposition to Nazism. In the name of the pope, Pacelli summoned Innitzer to Rome for a meeting. Arriving in the evening of April 5, Innitzer had a long meeting with Pacelli that journalists described as a “stormy session.” The next day, the Austrian met with the pope, who treated him more gently as a wayward son. Innitzer then issued a new statement basically retracting his earlier one and upholding the rights of the church. His penance did not last long: when he returned to Vienna he flew the swastika over his cathedral. By the following fall, however, Innitzer had broken with the Nazis and became an object of their attacks.

In the meantime, Pacelli sent a memorandum to Joseph P. Kennedy, then ambassador to the United Kingdom, whom the cardinal had met during his American visit, to say that Innitzer had originally spoken without the Vatican’s knowledge or approval and had now issued a new statement, which was enclosed. Pacelli asked Kennedy to pass the information on to Roosevelt, as Charles Gallagher, S.J., wrote in America (9/1/2003). Kennedy also had the document sent to the State Department, which published it in Foreign Relations of the United States in 1955.

Aside from archival documents, there are other indications of Pacelli’s aversion to the Nazi agenda. In May 1937, when the Mundelein affair had just begun, U.S. Ambassador William Phillips met Pacelli at a dinner arranged by the Irish ambassador to the Holy See. Phillips recorded in his diary how enthusiastic the cardinal was about his trip to the United States and his visit with Roosevelt, but “he talked mostly about his difficulties with Germany. He mentioned that these were growing worse every day and he foresaw the time before long when the entire German people would become ‘pagans.’” Phillips characterized Pacelli as having “great personal charm and is a man of force and character with high spiritual qualities, an ideal man for Pope if he can be elected.” When Pacelli was elected, Phillips opined that his choice of name “is an intimation to the world that he intends to pursue the strong policy of Pius XI.” Phillips’s wife, Caroline, wrote that Pacelli’s election was “to the joy of everyone except perhaps Hitler & the Duce.” Phillips added a further note that he hoped Roosevelt would appoint a representative to the coronation “to show the respect and admiration which all Americans must feel for the new Pope.” In an unprecedented action, Roosevelt appointed Kennedy as the first American representative at a papal coronation. Subsequently, on Dec. 24, 1940, he appointed Myron C. Taylor as his personal representative to the pope, a substitute for formal diplomatic relations.

Reasons for Silence

Pacelli’s years as pope have been the subject of intense scrutiny. Was he silent because of insensitivity to the plight of Jews and other victims of Nazi aggression, such as Polish Catholics? A review of the available historical data points to a different conclusion.

In June 1941 Germany invaded the Soviet Union, and Roosevelt immediately announced the extension of Lend Lease to this new victim of aggression. If Catholics supported this policy, did it mean they were cooperating with Communism, which had been condemned in 1937 in Divini Redemptoris? In a radio address from Washington funded by the State Department, Bishop Joseph Hurley of St. Augustine, a former Vatican official, drew the distinction between cooperation with Communism and aid to the “Russian” people. This created some public controversy among the American bishops, but the Vatican ultimately adopted Hurley’s position as its own.

On Dec. 17, 1942, eleven allied nations, including the Soviet Union, condemned the Nazi extermination of Jews. Critics have noted that Pius XII refused to sign the declaration, but they do not mention the reason for his refusal. The cardinal secretary of state, Luigi Maglione, explained that if the Holy See was to maintain its policy of “impartiality,” it would also have to condemn by name the Soviet Union, which had also committed atrocities. In his Christmas allocution a week later, however, the pope called for a postwar reconstruction of society on a Christian basis. To prevent future war, he urged humanity to make a vow to all the victims of the war, including “the hundreds of thousands of persons who, without any fault on their part, sometimes only because of their nationality or race, have been consigned to death or to a slow decline.” Many critics have claimed that the pope was so vague that it was not clear that he meant the Jews. Even strong papal supporters like Vincent McCormick, S.J., an American in Rome and former rector of the Pontifical Gregorian University, thought the allocution “much too heavy...& obscurely expressed.” McCormick suggested that the pope should abandon his German tutors and “have an Italian or Frenchman prepare his text.” Harold Tittmann, Myron Taylor’s assistant who resided in the Vatican, also reported that the statement contained vague generalities, but added that the allusion to the Jews was clear enough that the German diplomats boycotted the pope’s midnight Mass.

Pius did have an abstract manner of speaking. In this, he may have been guilty of pope-speak or Vaticanese, the use of which was not unique to him. For example, on Oct. 25, 1962, in the midst of the Cuban missile crisis, John XXIII gave a radio address in which he called on the world’s leaders to negotiate rather than resort to war, but he never mentioned Cuba or Kennedy or Khruschev. Everyone at the time understood the context.

Other documents provide a broader context for understanding the actions of Pius XII. On Feb. 18, 1942, William Donovan, then director of the office of Coordinator of Information, forerunner of the Office of Strategic Services, informed Roosevelt that he had set up a State Department liaison for the Vatican and that AmletoCicognani, the apostolic delegate, had paid him a long visit and pledged to turn over all information gained through diplomatic channels. Unfortunately, there is no further documentation on this issue, but it would be unlikely that information was transmitted in writing. Another provocative document is Harold Tittmann’s report in June 1945 that Josef Mueller, a leader of German resistance, told him that throughout the war Pius XII had followed the advice of the resistance not to attack Hitler personally because the German propaganda machine would construe it as an attack on the German people.

With this survey, I have attempted not to argue that Pius was not silent in regard to the plight of the Jews and other victims, such as the Poles, but rather to deny that this silence was due to indifference. When he was secretary of state, Pius learned that public protests had little effect on Hitler. As we have seen, the charge that he ever sided with Hitler out of fear of Communism is groundless. Many historians, including this writer, have asked that the Vatican open the Pius XII archives, but I suspect that the archival material will only add more shades of gray to a man who was trying to govern the church during an unprecedented period of inhumanity.

Listen to an interview with Gerald P. Fogarty, S.J.